Mountains on Zurich’s doorstep

The mountains near Zurich are neither high nor, in most cases, technically challenging, but they play an important role in tourism and as a local recreation area. With their observation towers and guest houses, they are popular destinations for days out.

Uetliberg: paths and precipices

One Sunday morning in March 1840, following a convivial drinking session in the newly opened guesthouse at Uto Kulm, Friedrich von Dürler (1804–1840), secretary of Zurich’s poor relief organisation and a celebrated mountaineer, decides to walk home. He falls to his death in a steep gully, as Gottlieb Binder recounts in his book “Der Ütliberg und die Albiskette”.

Today, the spot where Dürler parted ways with his companions is marked by the Dürler stone. It is a reminder that in addition to gentle paths such as the Denzlerweg, Laternenweg and Hohensteinweg, there are also uneven tracks and trails with steep drops on the way up Zurich’s local mountain. They reveal the untamed side of the Uetliberg, and the Fallätsche is a prime example.

When they are not climbing, hiking or walking around the Uetliberg, people have also taken the time to write about it. It has become the setting for literature, playing a key role in works by Gottfried Keller (1819–1890) and in the imaginative account “Die Erstbesteigung des Uetlibergs mit Sauerstoff” (The First Ascent of the Uetliberg with Oxygen).

Opening up to tourism: donkey milk and steam locomotives

The author of the first Swiss travel guide, Johann Gottfried Ebel (1764–1830), described the spectacular panoramic views from the Uetliberg as far back as 1805: “Here is the grand and magnificent view, just as at the Albis lookout station yet different, less constrained and more expansive owing to the different location.”

Tourism on the Uetliberg really took off in around 1840, when city dwellers began to appreciate its potential as a local recreation area and the first guesthouse was built at the summit of the mountain. The landlord offered donkey milk and whey cures. This first period of tourism was not especially profitable, because business from day trippers depended on the weather and the path up the mountain was arduous. The situation did not improve until the Uetliberg railway line was built towards the end of the 19th century.

The Uetliberg is a popular walking and recreation area, but also a place where commercial interests and public expectations collide, leading to conflicts that need to be resolved.

Tourism on the Bachtel

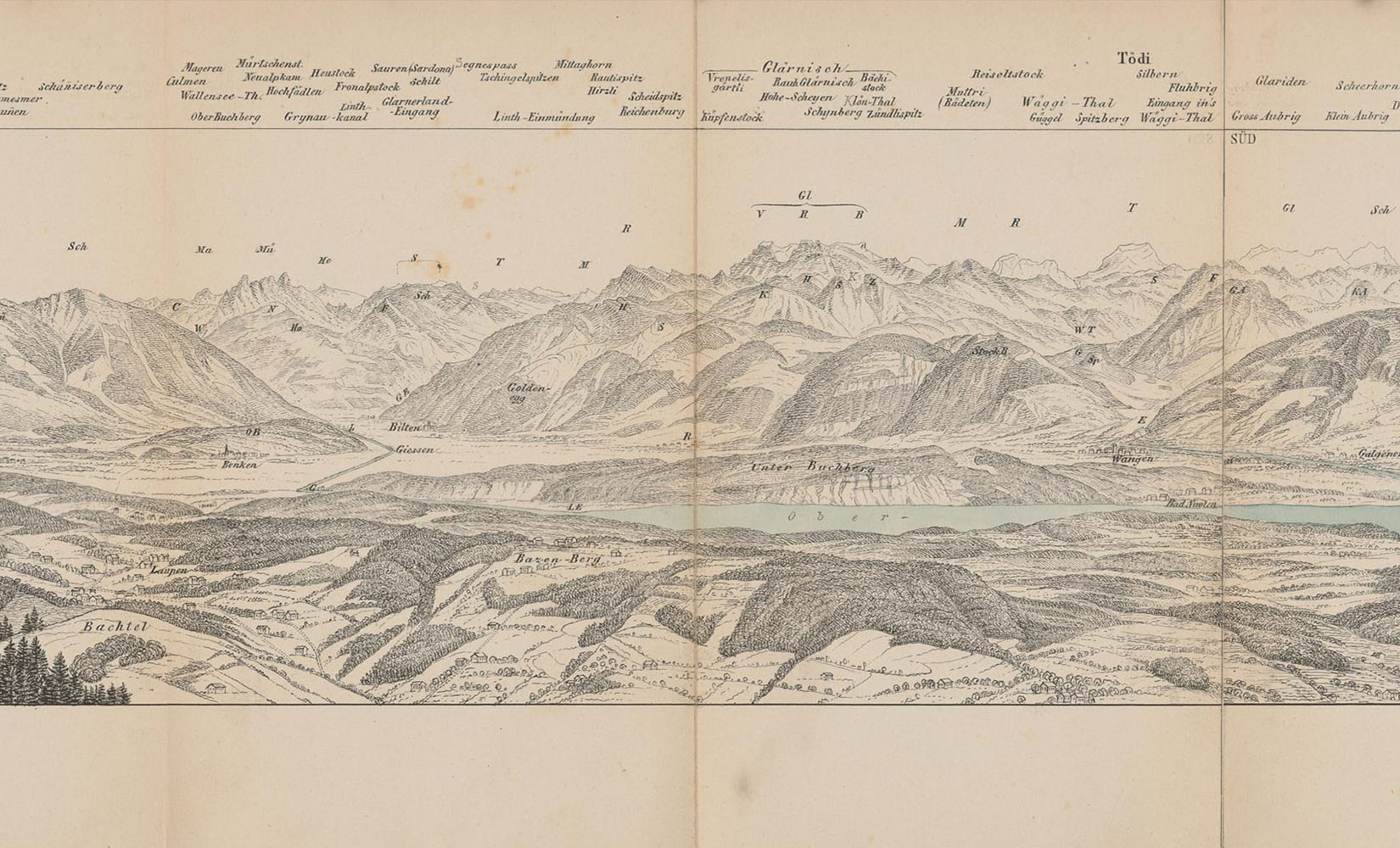

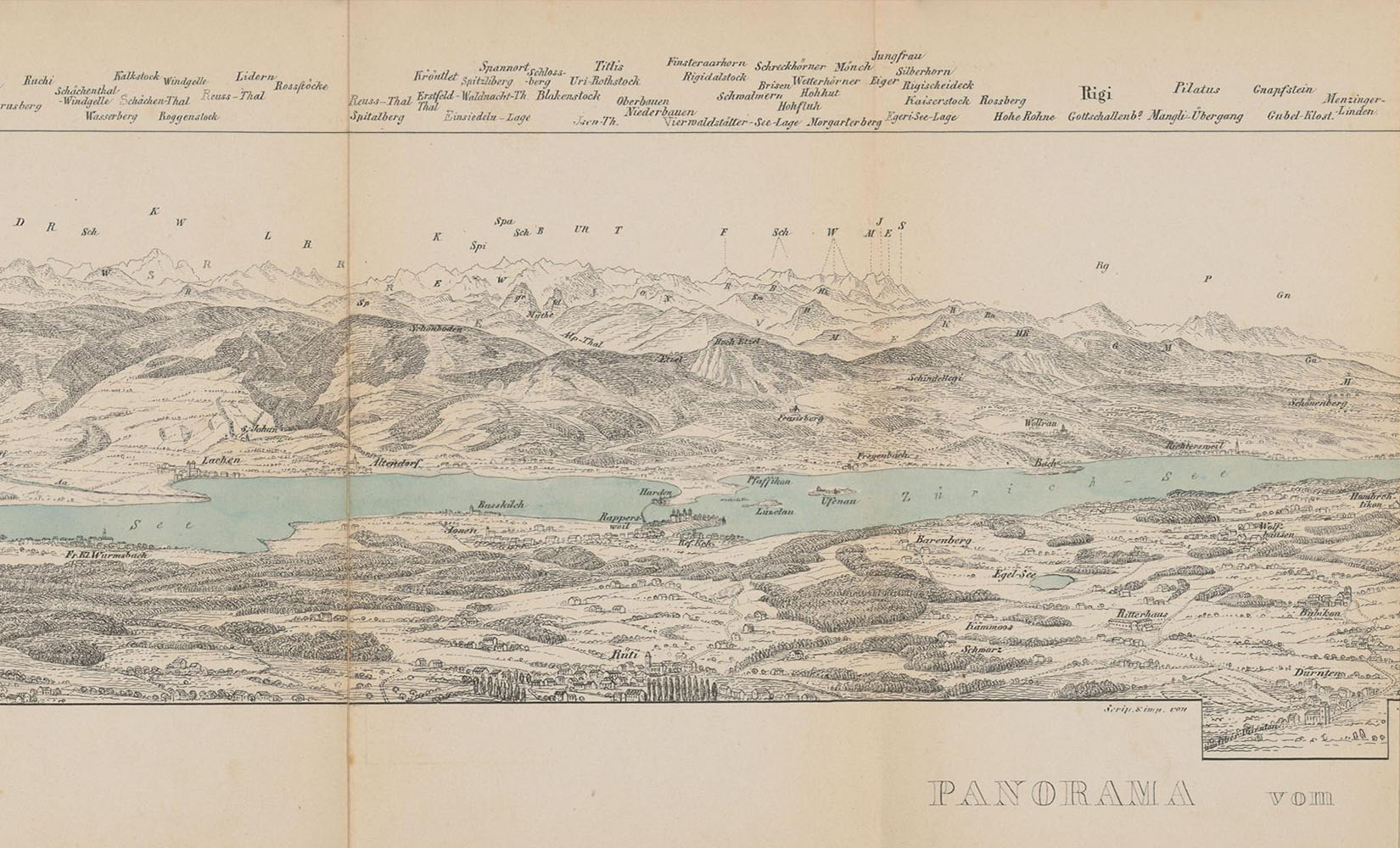

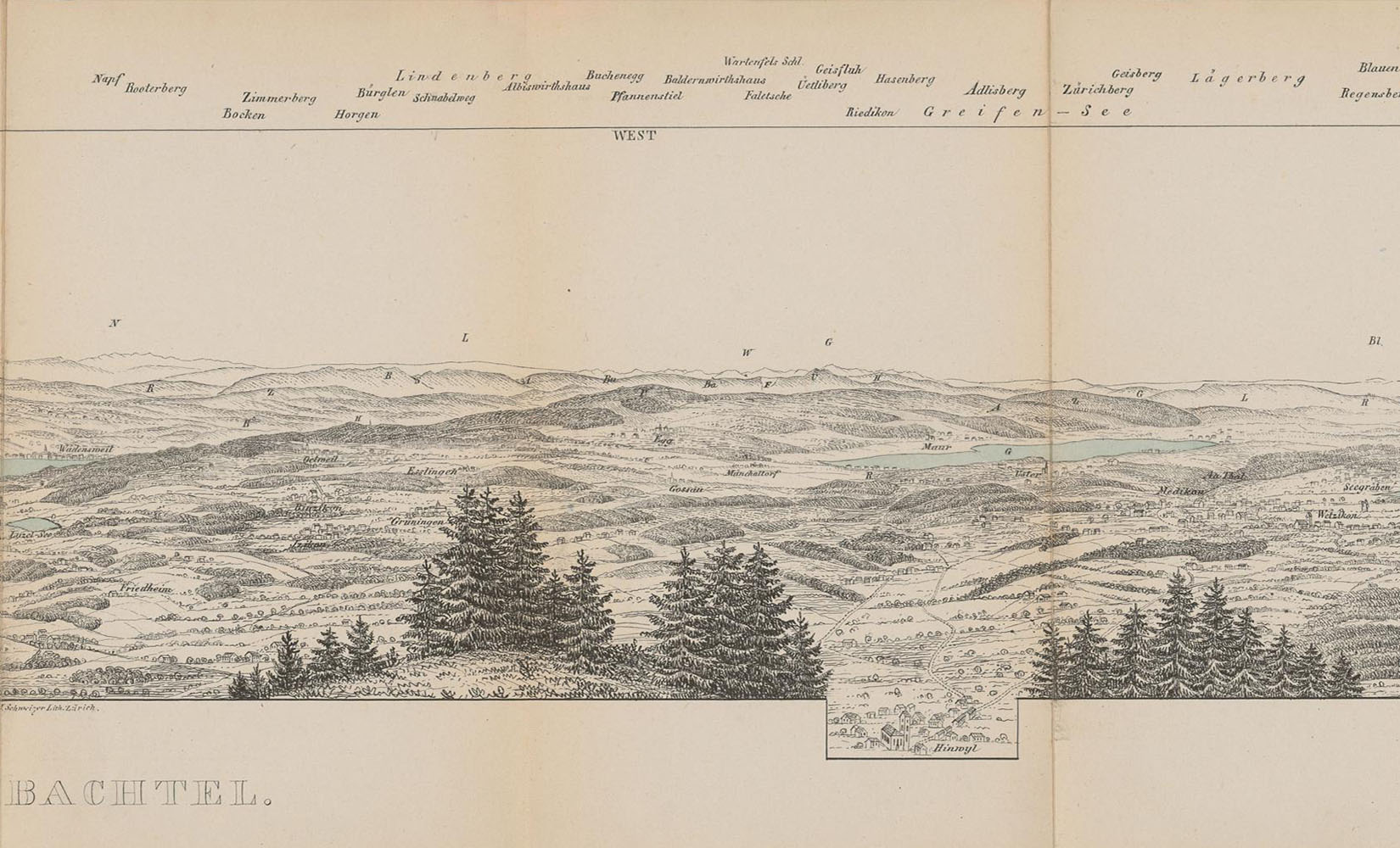

The Bachtel, often known as the “Rigi” of the Zürcher Oberland, is popular for its scenic views. Old travel guides praise its panorama. Gottfried von Escher’s (1800–1876) “Neuestes Handbuch für Reisende in der Schweiz”, published in 1851, states: “extensive view of the upper part of Lake Zurich [...] and the fine mountain chain from Sentis to the high Alps of the Bernese Oberland.”

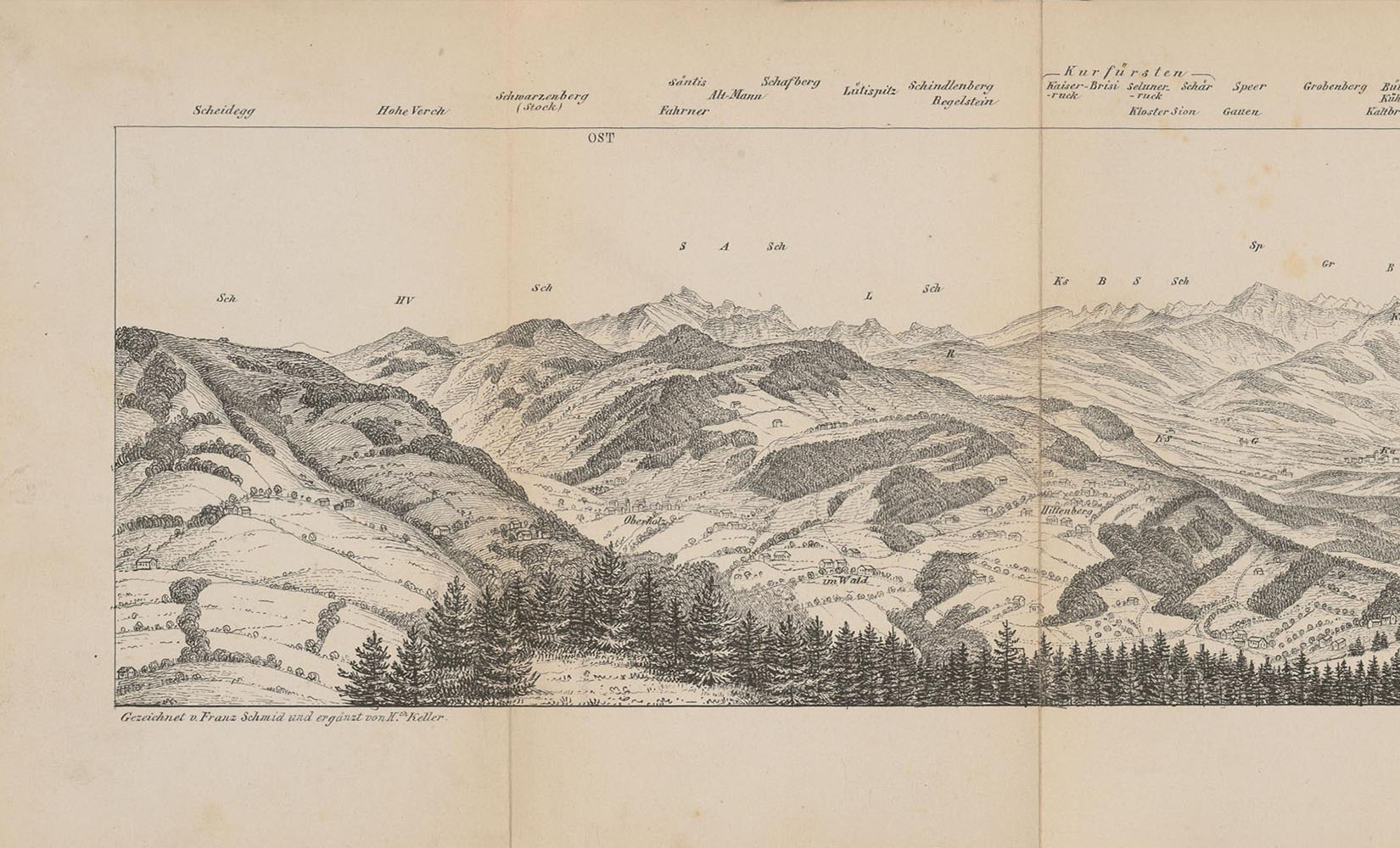

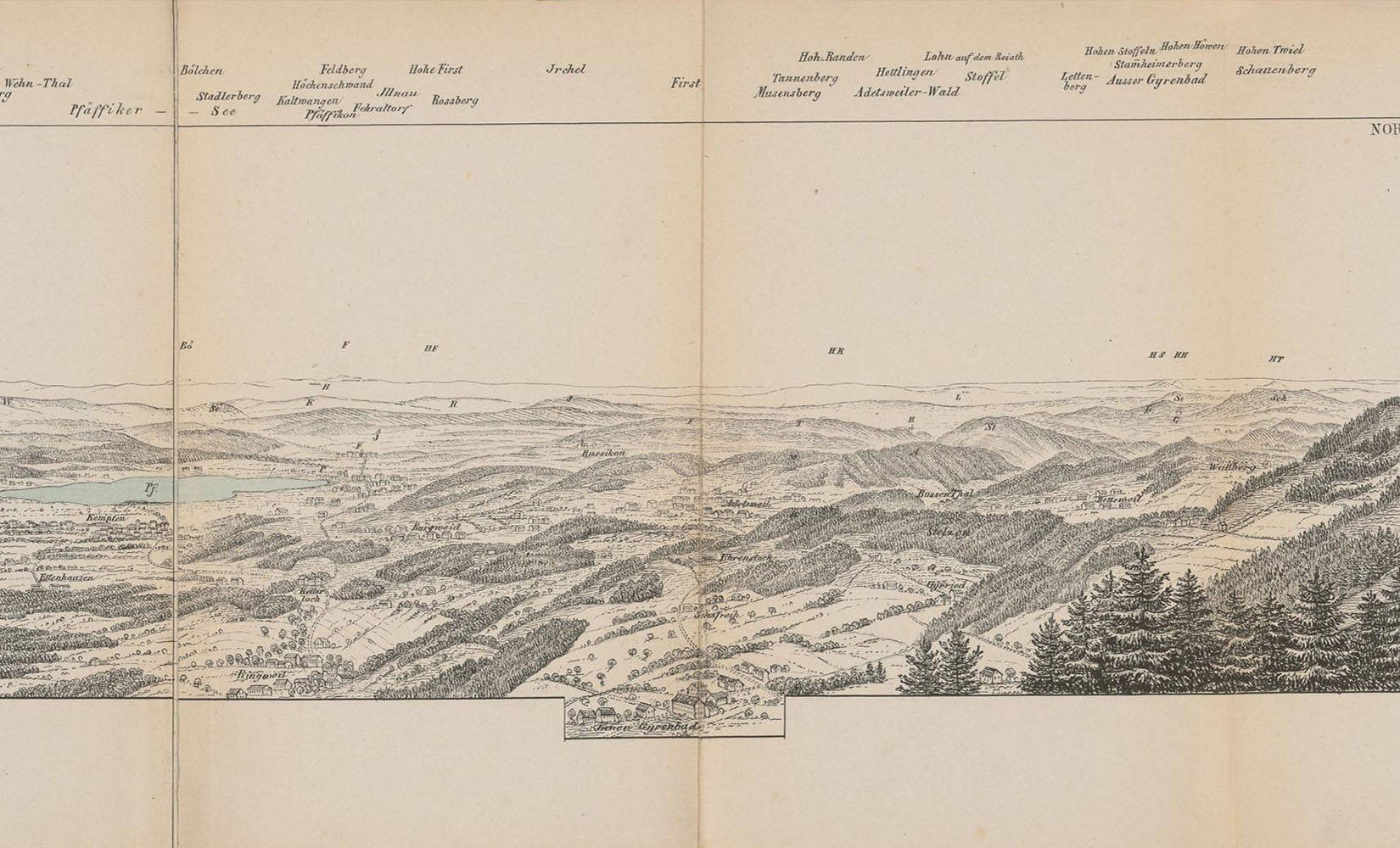

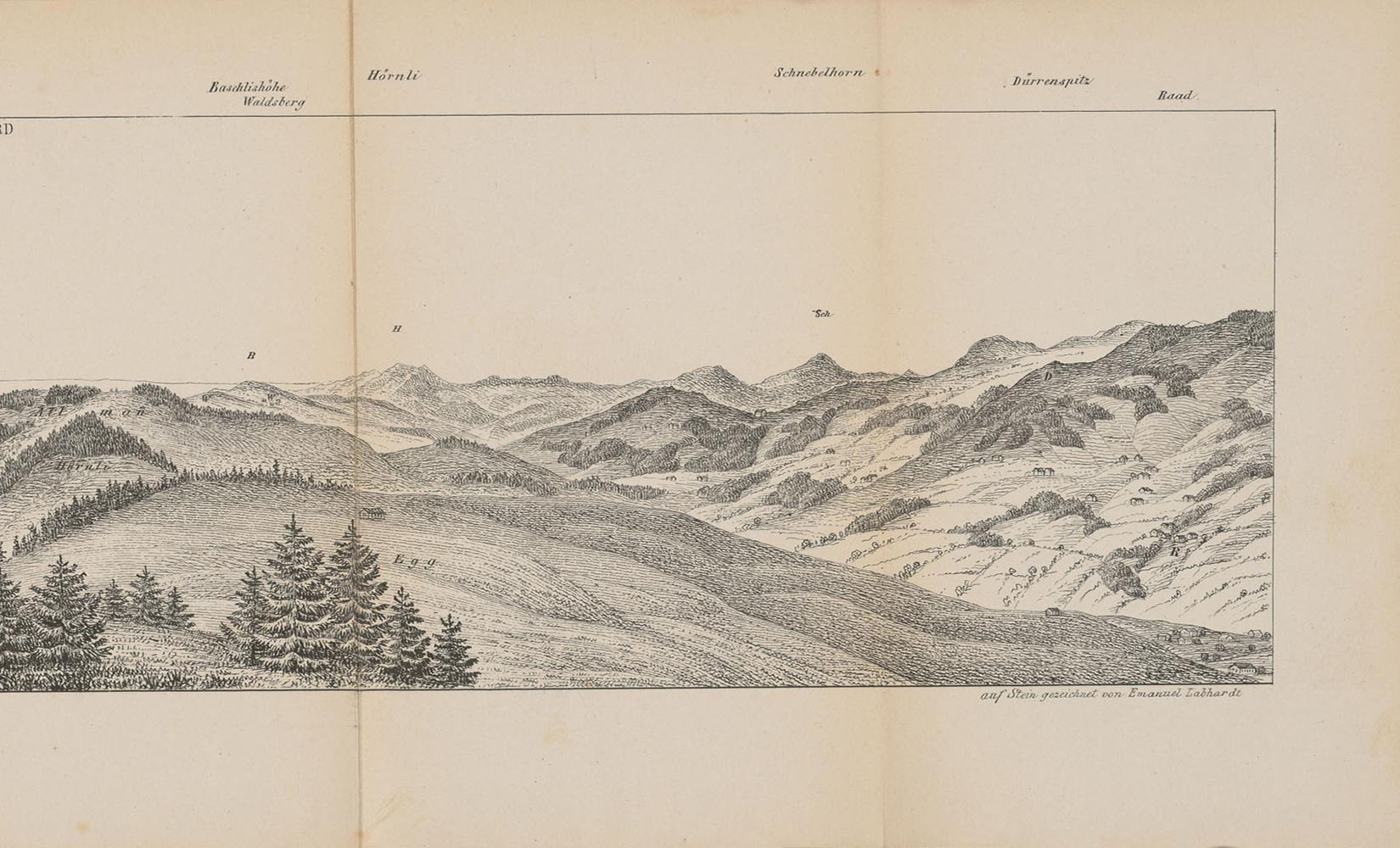

The 19th-century enthusiasm for the natural world also attracted the educated middle class to the mountains. The well-known panorama draughtsman Heinrich Keller (1778–1862), for example, captured the all-round view from Bachtel Kulm in an 1849 panorama.

The efforts made to promote tourism were considerable. Activities such as Swiss wrestling (Bachtel Schwinget), stone putting and finger pulling were staged, a spa and guest house were built in 1856, followed later by an observation tower. The early 20th century then saw the arrival of winter sports on the Bachtel.

The old tower

“But on the platform of the Bachtel tower, after the 30 metres, we felt like summiteers. The wind in our hair. To the south the mountains, Glärnisch and Tödi [...]” is how the writer Emil Zopfi, who grew up on the east side of the Bachtel, describes the old tower.

In a bid to increase its attractiveness, the landlord of the first guest house on the Bachtel had a bowling alley built in the 1870s, along with a wooden tower with a viewing platform and coloured windows. In January 1890, a winter storm swept over the Zürcher Oberland, reducing the tower to a pile of timber and shards of coloured glass.

Members of the SAC Section Bachtel collected funds to build a new steel tower with a viewing platform and peak map. After almost 100 years, it was replaced by a new transmitting station. It was dismantled, renovated and, seven years later, re-erected on the Pfannenstil, where it is known as the “old Bachtel tower”.

Incidentally, the Bachtel is not the only mountain to give its name to a section of the Swiss Alpine Club: the SAC Section Uto is named after a short form of the name Uetliberg.

Lookout stations and hilltop fires

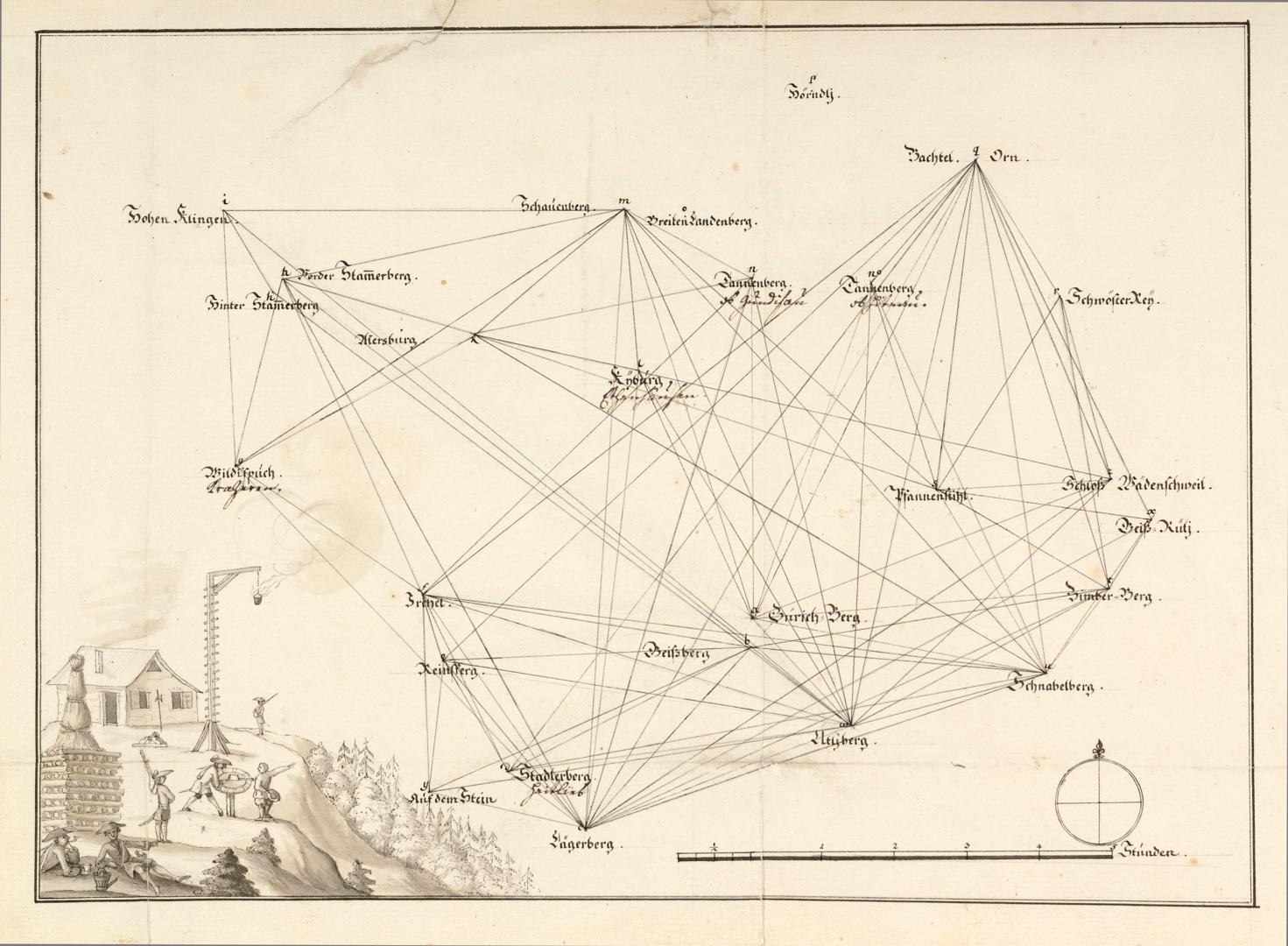

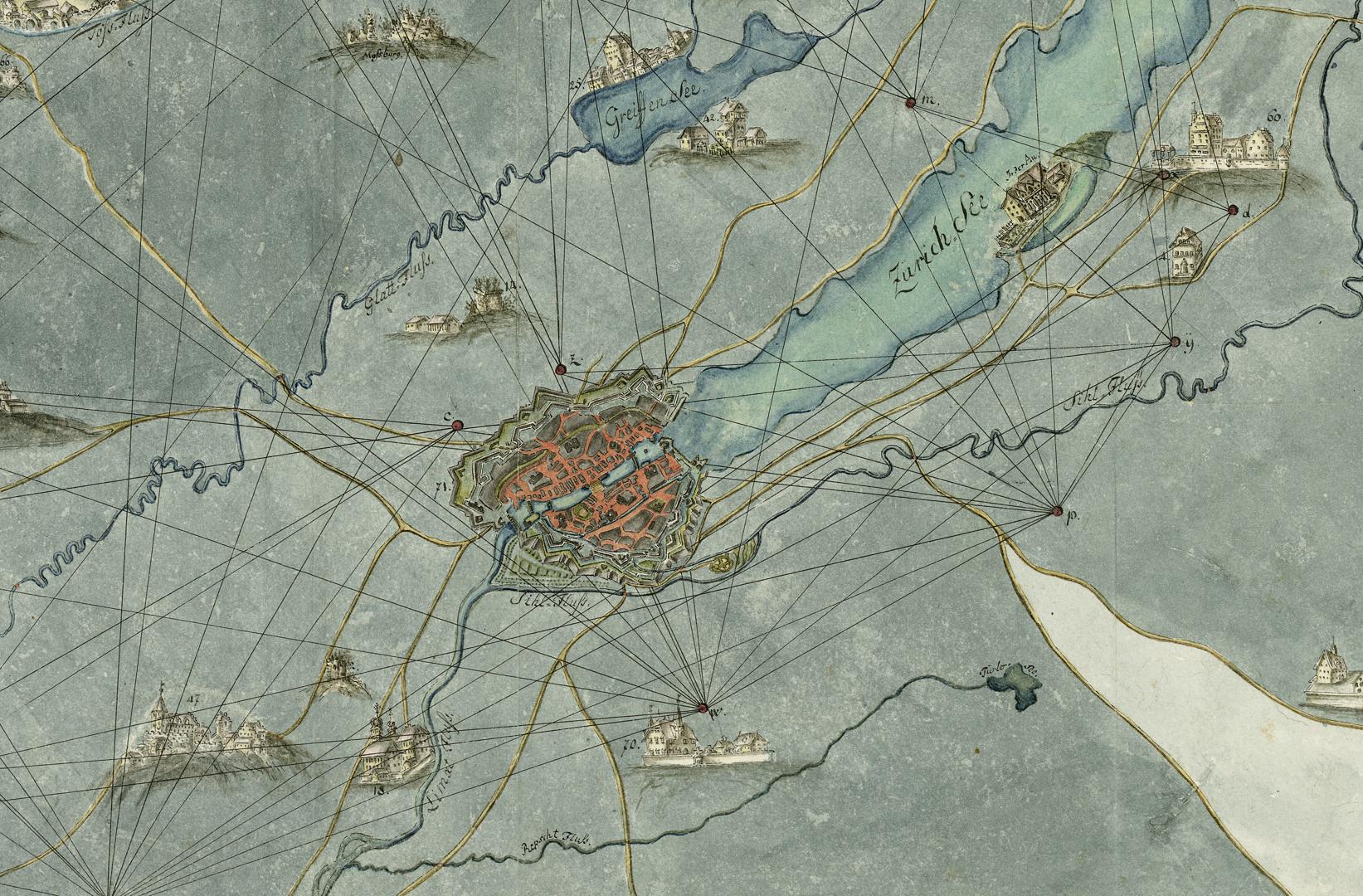

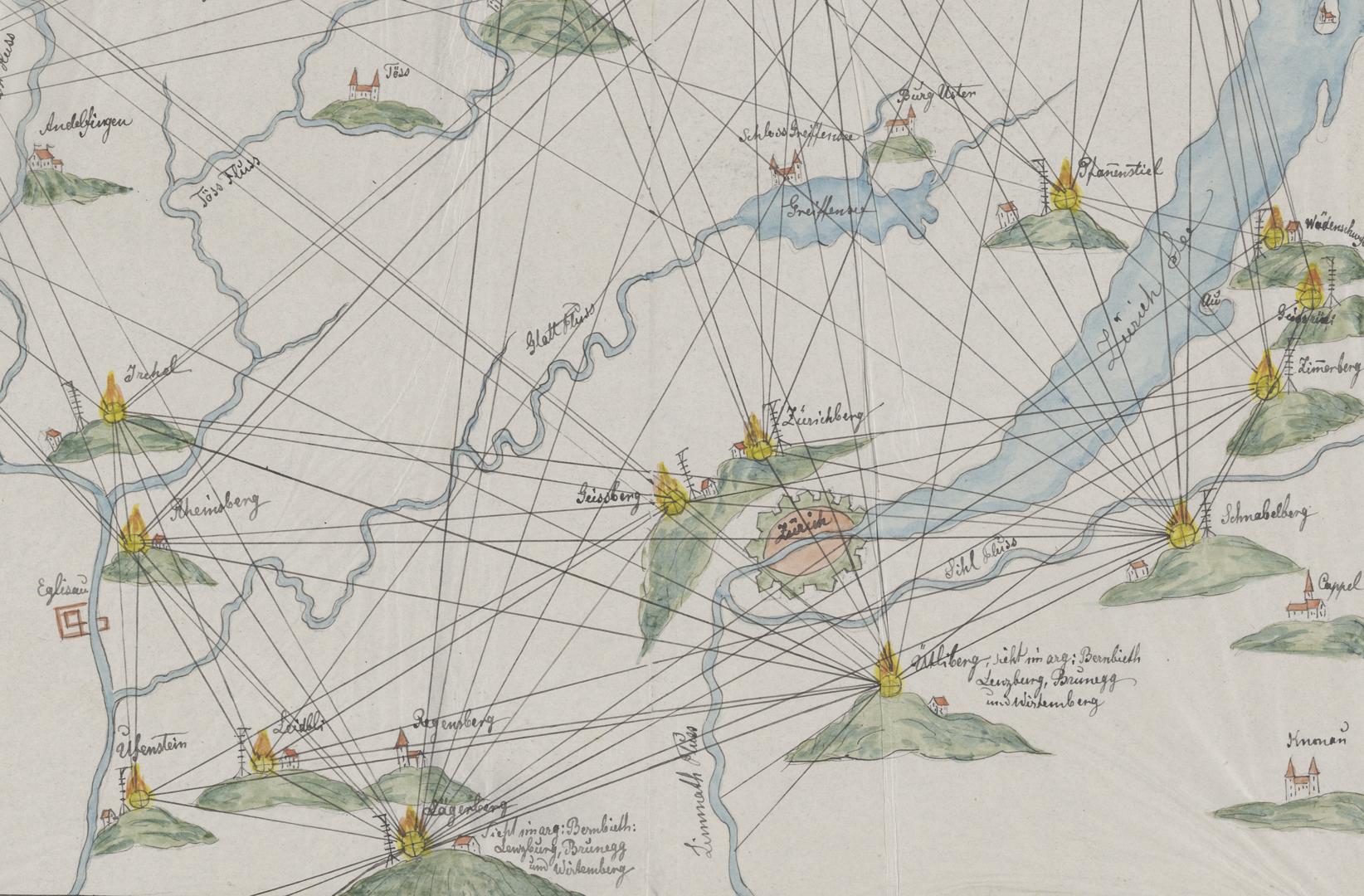

Clear skies and a golden autumn day draw numerous day-trippers to the top of the Uetliberg, Bachtel, Pfannenstil and other Zurich mountains such as the Stadlerberg and Zürichberg, keen to take in the spectacular views. But what, apart from the scenery, do these mountains have in common? All of them were once home to lookout stations.

These are elevated locations in the canton of Zurich commanding good views of the surrounding area on which installations were set up to warn of danger. They formed part of an alarm system that can be regarded as a precursor of the electric telegraph, because it was used to send signals. At night this was done using fire, by day using smoke, and in fog by firing cannons.

Today, the lookout stations are a thing of the past, but field names such as Guggershörnli and Wachthubel remain as reminders of the former alarm system. Observation or radio towers stand on hills that are popular destinations for outings and places where hilltop fires are often lit.

Further reading

Our sports and mountaineering experts recommend:

- Zürcher Hausberge by Marco Volken and Remo Kundert: a successful classic. This hiking guide to mountains around Zurich includes any that can be explored from the city in a day using public transport.

- “Der Uetliberg” by Stefan Schneiter. The author and historian takes readers on a fascinating journey to the Uetliberg, past and present

- “Sehnsucht nach den grünen Höhen: literarische Wanderungen zwischen Pfannenstiel, Churfirsten und Tödi” by Christa and Emil Zopfi. With references to more than 50 authors

Daniel Stettler, economy, sport and mountaineering expert

and contact for the SAC library at the ZB Zürich

October 2021

Header image: The Uetliberg in a sea of fog, with the Glarus Alps in the background, around 1900 (Edition Photoglob/ZBZ)