OK – Oskar Kokoschka

Born in Lower Austria, Oskar Kokoschka (1886–1980) is regarded as one of the most important artists of Expressionism, an outstanding portraitist and an idiosyncratic writer. His widow generously donated his literary estate to the Zentralbibliothek Zürich. We take a look at the world of “OK” …

“And since I am a man who experiences the world through his eyes, not his ears, I will speak of what I have seen.”

Oskar Kokoschka in his autobiography “My Life”

Oskar Kokoschka and Zurich

Many are surprised to learn that the literary estate of the world-famous painter Oskar Kokoschka is today held by the Zentralbibliothek Zürich. The artist, who changed nationalities on several occasions and resided in a number of countries, never lived in the city for any length of time.

He first came to Switzerland in early 1910, at the age of 23, in response to an invitation from his patron Adolf Loos. There, by Lake Geneva, he painted portraits of tuberculosis patients and developed his artistic vision. (He later claimed this visit had taken place earlier, in 1908, thus positioning him as a precursor of Expressionism.) In 1912 he travelled to Switzerland a second time, accompanied by his lover Alma Mahler, and painted in the Bernese Oberland.

Zurich played an important role early in his career, as the following highlights demonstrate.

Expressionist portraits in the Kunsthaus

In May 1913, the Kunsthaus Zürich, under its Director Dr Wilhelm Wartmann, exhibits twelve Expressionist portraits by the artist, who is still largely unknown in Switzerland, with the “grotesque” and “brutal” images generating headlines.

The “Züricher Post” writes: “When one reaches the place where the Oskar Kokoschka images hang, one’s first reaction is to step back in horror. It is as if figures from E. T. A. Hoffmann were suddenly manifesting themselves in the flickering light of the inn. [...] Gradually, the initial sense of repulsion wanes, one is drawn further and further into the pictures, and they begin to captivate and fascinate.”

![“Gradually, the initial sense of repulsion wanes [...]”: review in the “Züricher Post”, 30 May 1913, of Oskar Kokoschka’s portraits at the Kunsthaus (ZBZ)](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/zuerich/kokoschka/Timeline-1/Kokoschka-1.jpg)

Zurich Dada and Kokoschka

On 14 April 1917, the Swiss première of Kokoschka’s play “Sphinx and Strawman” takes place at the Galerie Dada on Zurich’s Bahnhofstrasse, with the Dadaists Tristan Tzara, Marcel Janco, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings and Friedrich Glauser all taking part; Kokoschka himself is not directly involved. The Jewish poet Albert Ehrenstein reads his own verses on Kokoschka.

At the same, time, the gallery’s “Sturm” exhibition displays portraits by Kokoschka alongside works by Max Ernst, Johannes Itten, Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee.

That same year, the Kunsthaus Zürich also includes him in an exhibition of German artists. It shows him again a year later, this time in the context of Viennese painting.

Kunstsalon Wolfsberg

In August 1923, Kokoschka, who is now a professor of art at the Dresden Academy, travels to central Switzerland and Lake Geneva. The holiday, taken together with the Russian Anna (Niuta) Kallin, is actually an escape from Dresden: he claims in a letter to his mother to be “heartily sick” of the city.

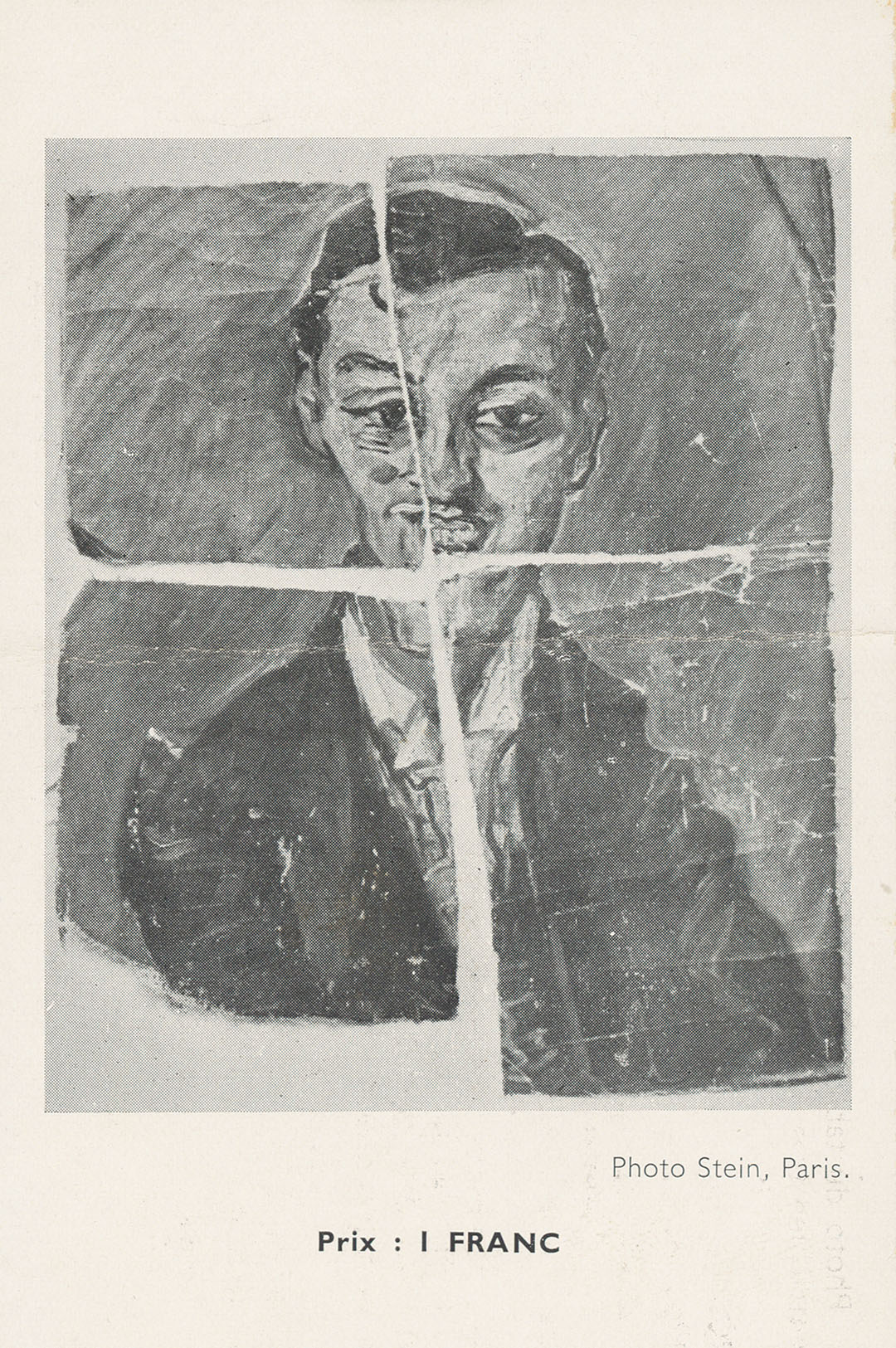

In September and October, the Kunstsalon Wolfsberg in Zurich shows 71 of his watercolours, drawings and prints, advertising the presentation with the colour lithograph “Self-Portrait from Two Sides”.

A year later, Kokoschka deposits 70,000 Marks – the proceeds from the first substantial sale of his works – with a Swiss bank.

First solo exhibition at the Kunsthaus

Oskar Kokoschka’s most comprehensive solo exhibition to date is held in 1927, once again at the Kunsthaus Zürich. His energetic champion Wilhelm Wartmann wants to provide as comprehensive an overview as possible. Importing the exhibits, all but one of which are in foreign ownership, causes some difficulties. Four of them are subsequently acquired by the Kunsthaus, and two by the Kunstmuseum Winterthur.

In all, ten exhibitions including works by Kokoschka take place under the auspices of Wartmann, whom Kokoschka calls “one of the few people with a real understanding of art today” (letter to Bettina A., 1 April 1953).

A platform in Zurich for an artist under fire

Despite the difficulties encountered by its first solo show devoted to Kokoschka, the Kunsthaus Zürich mounts a further presentation in 1935 featuring 25 new landscapes and cityscapes.

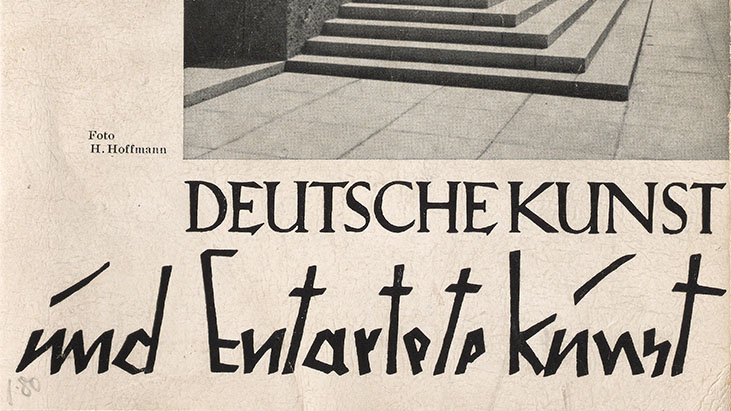

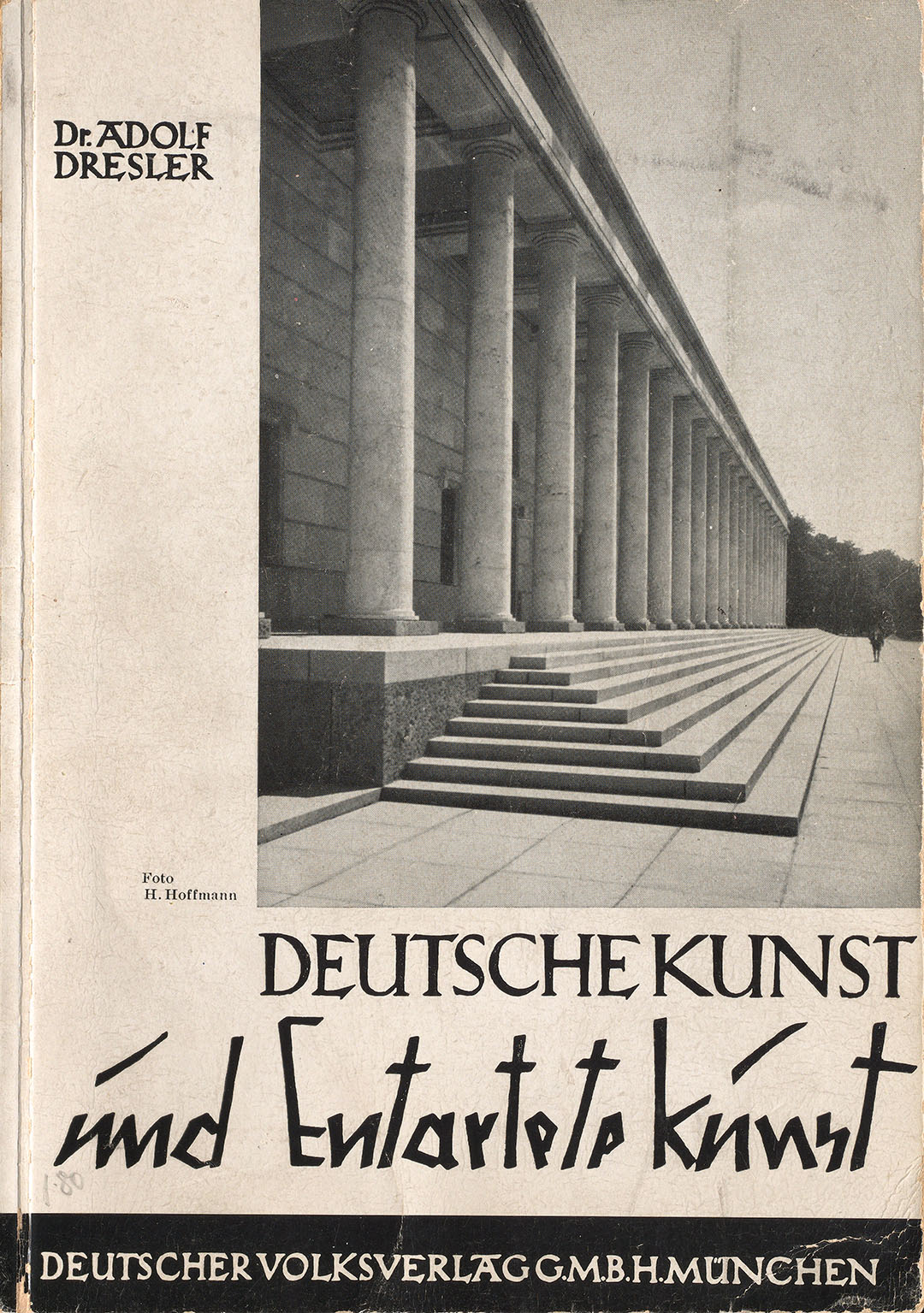

Kokoschka is grateful for the offer from Zurich during a period “that knows nothing but to trample on modern art and betray it when it is expedient to do so” (letter to Hans Posse, 7 April 1935). He experiences increasing rejection and losses due to political developments in his homeland. The Nazis regard his expressive depictions of human beings as “degenerate”, and in 1937 they are removed from German art collections. But Kokoschka, who has been living in Prague since 1934, refuses to conform in any way.

Post-war retrospective

In 1937, Wilhelm Wartmann writes that in little more than two decades, 270 works by Kokoschka have been shown in Zurich alone. But it will be another ten years before the “degenerate” artist himself is able to enter the country again, this time for the major 1947 retrospective in Basel and at the Kunsthaus Zürich. It shows many paintings that had been thought lost and is also a commercial success for Kokoschka. In summer, the NZZ publishes two samples of his storytelling: “The story of daughter Virginia” and “Childhood illness”.

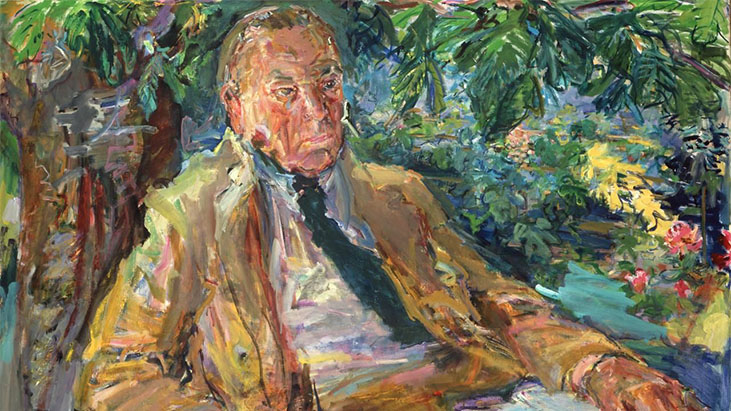

After ten years spent in exile in London, with houses as far as the eye can see, on returning to Switzerland he once again paints “landscapes in the light and open air” (letter to Hans Maria Wingler, 21 October 1947). In Valais, he paints the unconventional portrait of his patron Werner Reinhart which is now in the Kunstmuseum Winterthur.

Publications in Zurich

“Switzerland is now becoming ‘non-representational’ and abstract too, and museum directors here as elsewhere overvalue the rogue textile draughtsmen of our time to the detriment of classical, European painting”, Kokoschka writes in 1954 to the Zurich patron Emil Bührle.

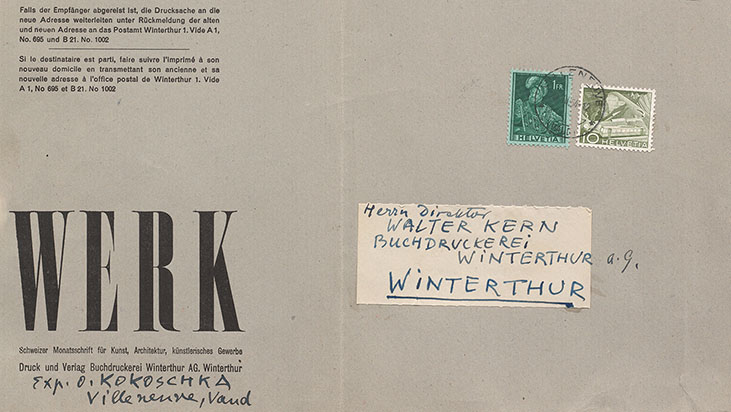

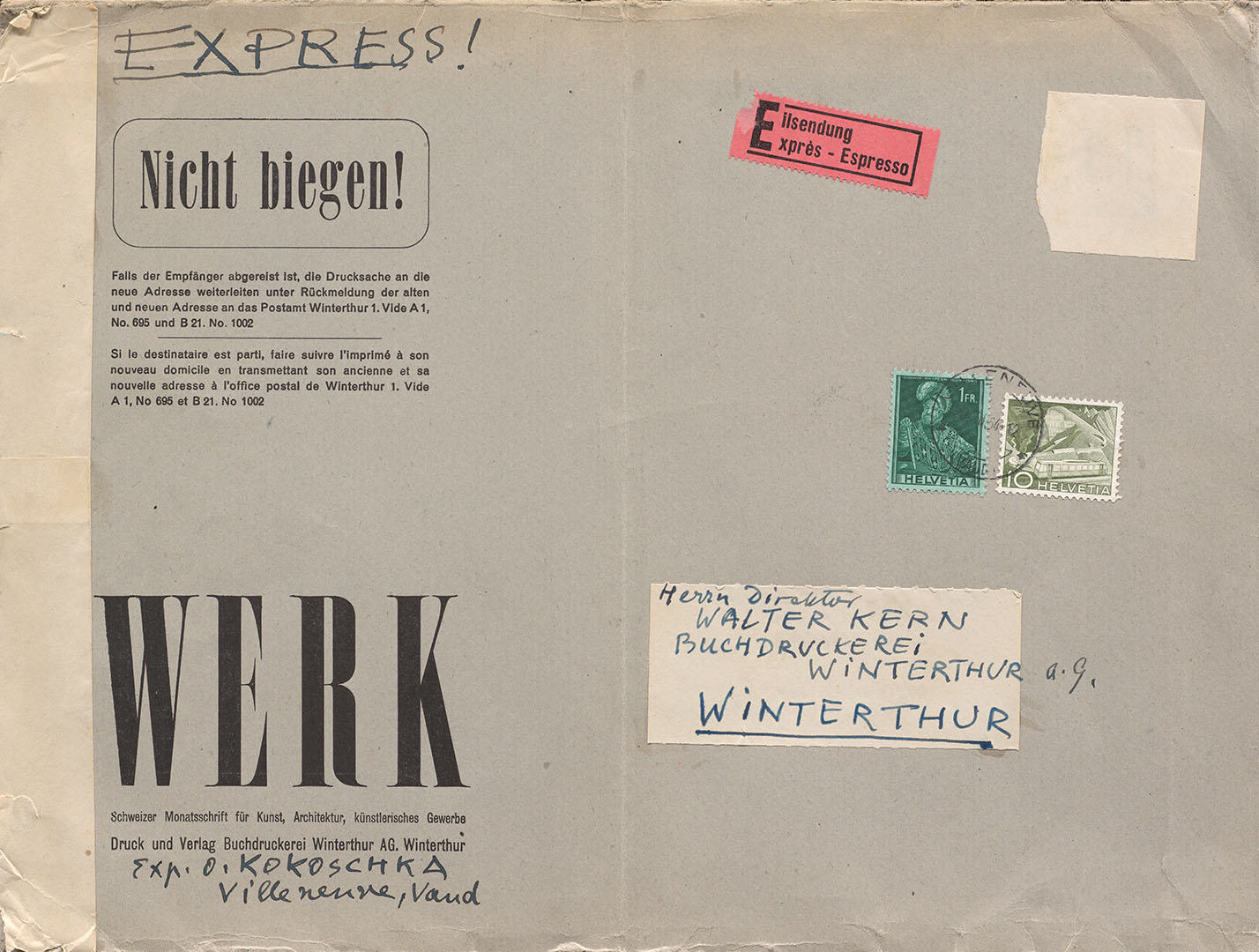

A number of art enthusiasts from Zurich come to his aid: in 1952 the publishing house Rascher releases “Gestalten und Landschaften”, while in 1955, Walter Kern in Winterthur publishes what Kokoschka considers the perfectly designed “Thermopylae” portfolio and follows it up in the journal “Das Werk”.

In 1956, the publisher Atlantis releases a volume of Kokoschka’s tales entitled “Tracks in the Quicksand”, with a “beautiful love story” and “much to excite” (letter to Bettina A., 21 December 1956).

Letters in the literary estate reveal how keenly Kokoschka cultivated his patrons.

A painter’s travel notes

In December 1982, to mark the donation of the estate by Olda Kokoschka, the ZB Zürich opens the exhibition “Oskar Kokoschka – a painter’s travel notes”. The “Neue Zürcher Nachrichten” newspaper reports that sketches, photos, manuscripts, printed works and letters convey “an image of the private Kokoschka”. It also comments on his close connection to Zurich. Curated by Dr Günter Birkner, Head of the Music Department, the presentation attracts so much interest that it is extended until February 1983.

Music and connections played a role in the gift: back in 1976, Elisabeth Furtwängler had transferred to the ZB Zürich the papers of the German conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who had died in 1954. The musician’s widow lives in Clarens, Vaud, and is a close friend of Olda Kokoschka.

New insights thanks to the ZB Zürich

100 years after Kokoschka’s first sojourn in Switzerland, the exhibition “Tracks in the quicksand − Oskar Kokoschka in a new light” takes place in Zurich. In association with the Fondation Oskar Kokoschka (FOK) in Vevey, the ZB Zürich offers new insights into the artist’s literary and pictorial oeuvre and his biography.

Curators Dr Régine Bonnefoit (FOK) and Ruth Häusler (ZB Manuscript Department) present many previously unknown documents from the holdings added to the estate in 2004. Their accompanying publication receives much praise from specialists.

The literary estate in the ZB Zürich

Olda Kokoschka (1915–2004), the artist’s widow, generously donated the literary estate to the ZB Zürich in 1981. She was won over by the then head of the Music Department, Dr Günter Birkner, and his vision of creating a centre for Kokoschka in Zurich. The first handover took place in 1982. In 1988 she established the Fondation à la mémoire de Oskar Kokoschka (FOK) based in Vevey, to whose care she entrusted his artistic estate.

Thanks to the tireless work of Günter Birkner and Hermann Köstler, Director of the ZB and trustee of the FOK, further parts of the estate were donated to or purchased by the ZB Zürich over the ensuing decades.

The last tranche handed over by the artist’s widow in 2004 comprised the personal documents (e.g. notebooks, diaries, identification documents), photos, early family letters and correspondence after 1980, various documentation compiled by the artist duo, and works by others about Kokoschka. The ZB Zürich regularly adds to these core holdings by making purchases of its own.

The following are three key areas that are extensively documented in the estate: Kokoschka as portraitist, poet and author, and letter-writer.

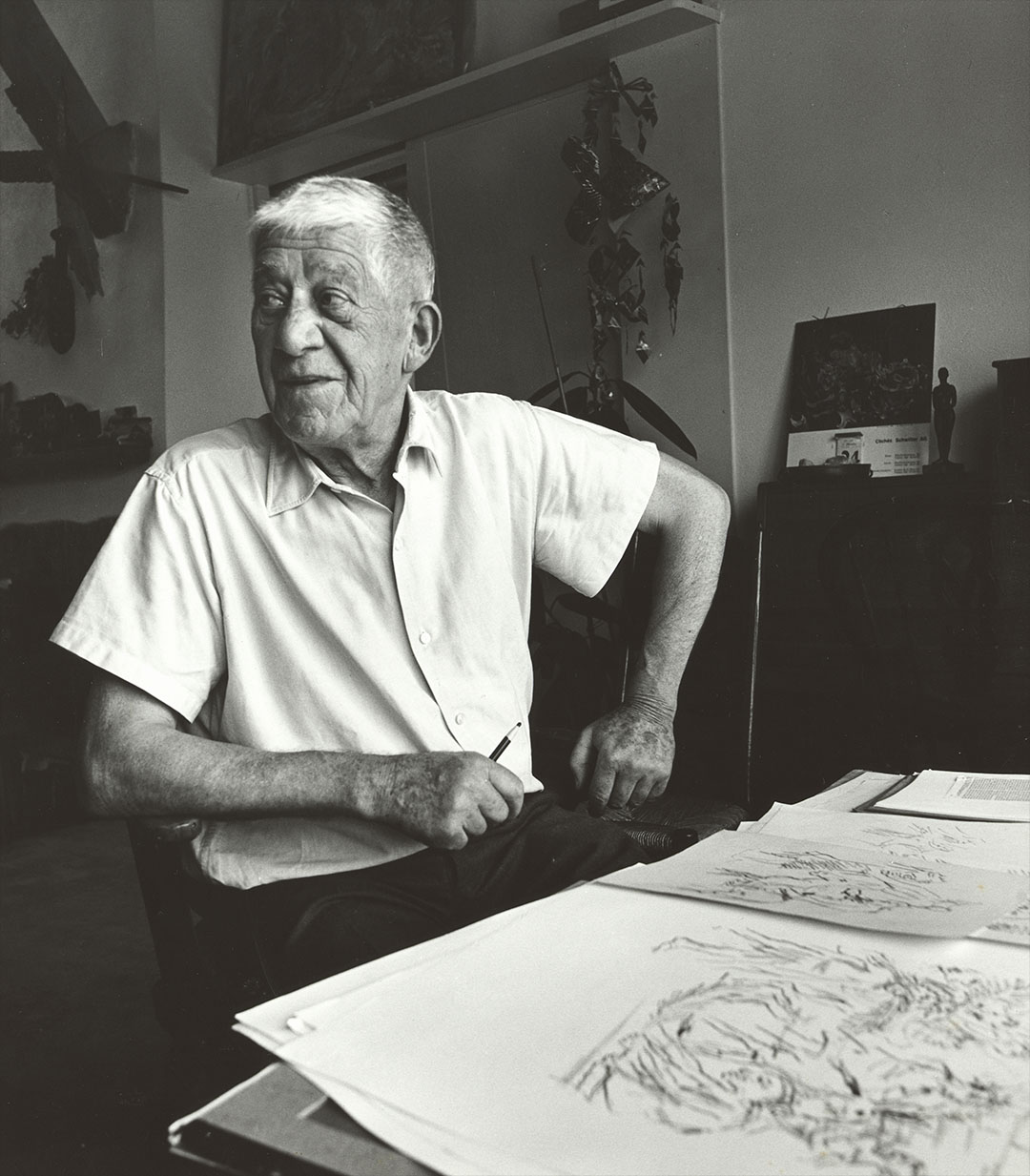

The portraitist

Kokoschka is one of the most important Expressionist portrait painters of the 20th century. His subjects included celebrities such as the cellist Pablo Casals, politicians such as Konrad Adenauer, leading experts of the time such as Auguste Forel, artists and art enthusiasts such as the patron Werner Reinhart from Winterthur, along with many faces captured at the places he visited on his travels, and about whom no more is known.

He was interested not in the outward appearance of those he painted but in their essential characteristics: their intellectual or spiritual physiognomy.

Letters by and about those who sat for him reveal interesting details of the painting sessions and enduring friendships. Kokoschka also frequently painted himself, using the medium to explore his own mental state. The pair of eyes in our header image are from the 1948 “Self-Portrait (Fiesole)”.

The storyteller, dramatist and admonisher

Oskar Kokoschka was also the author of audacious stage works, a gifted storyteller and an idiosyncratic speaker. For him, writing was an aesthetic pursuit and a socio-political commitment, but also a source of income. In 1953, the NZZ described his manner of speaking as “confessional causerie” and a “unique manifesto against something that he refers to as the academic”.

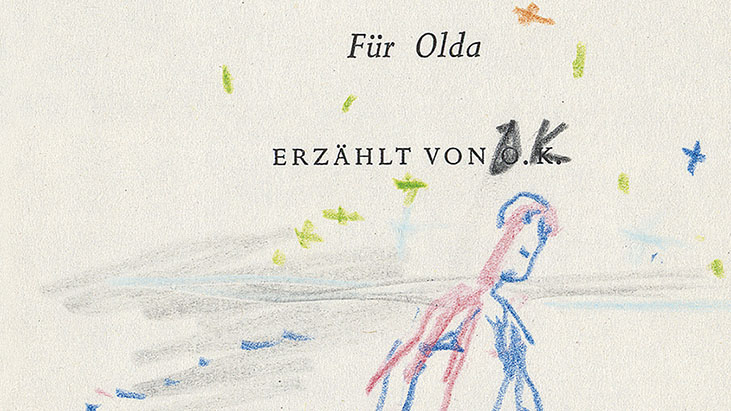

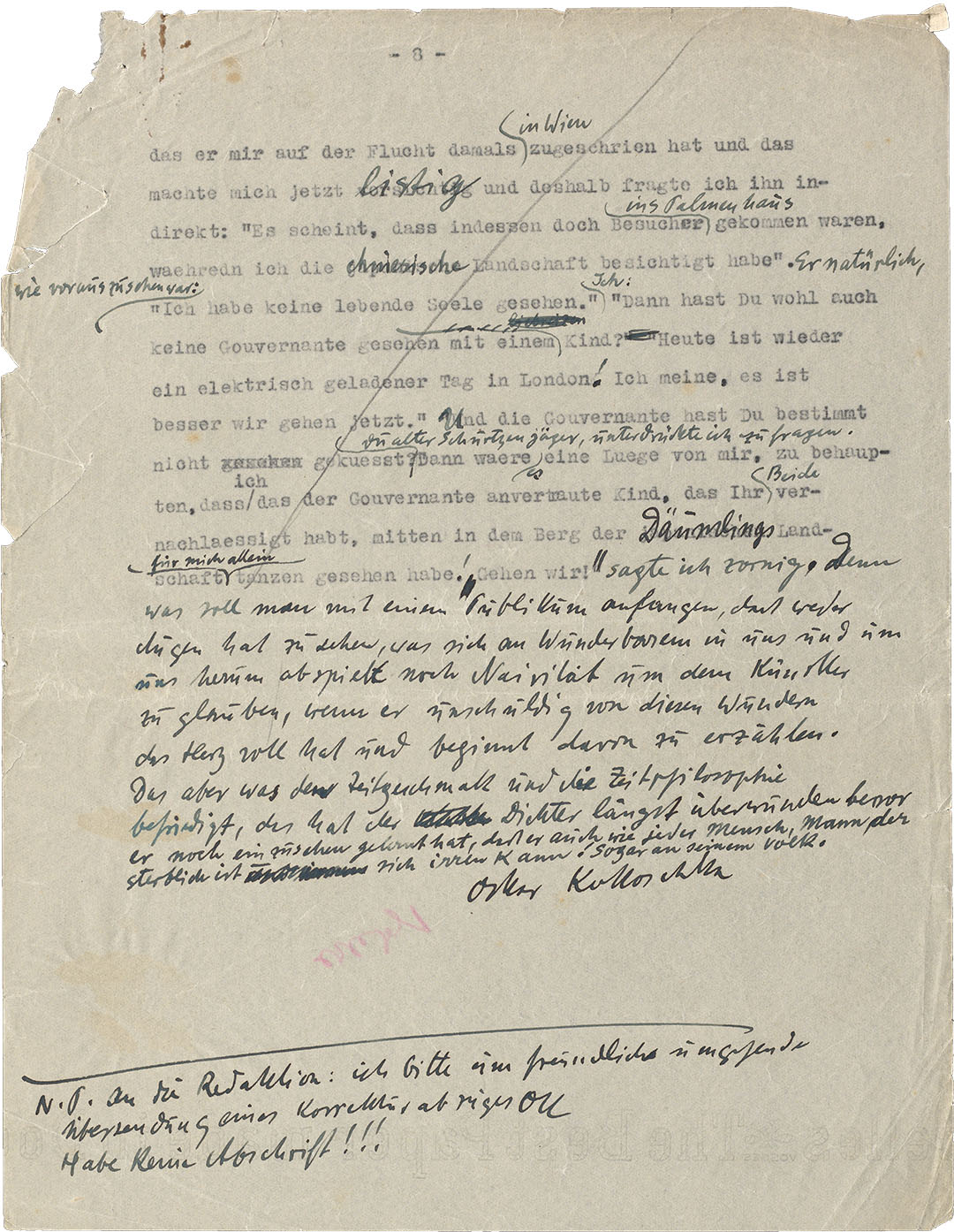

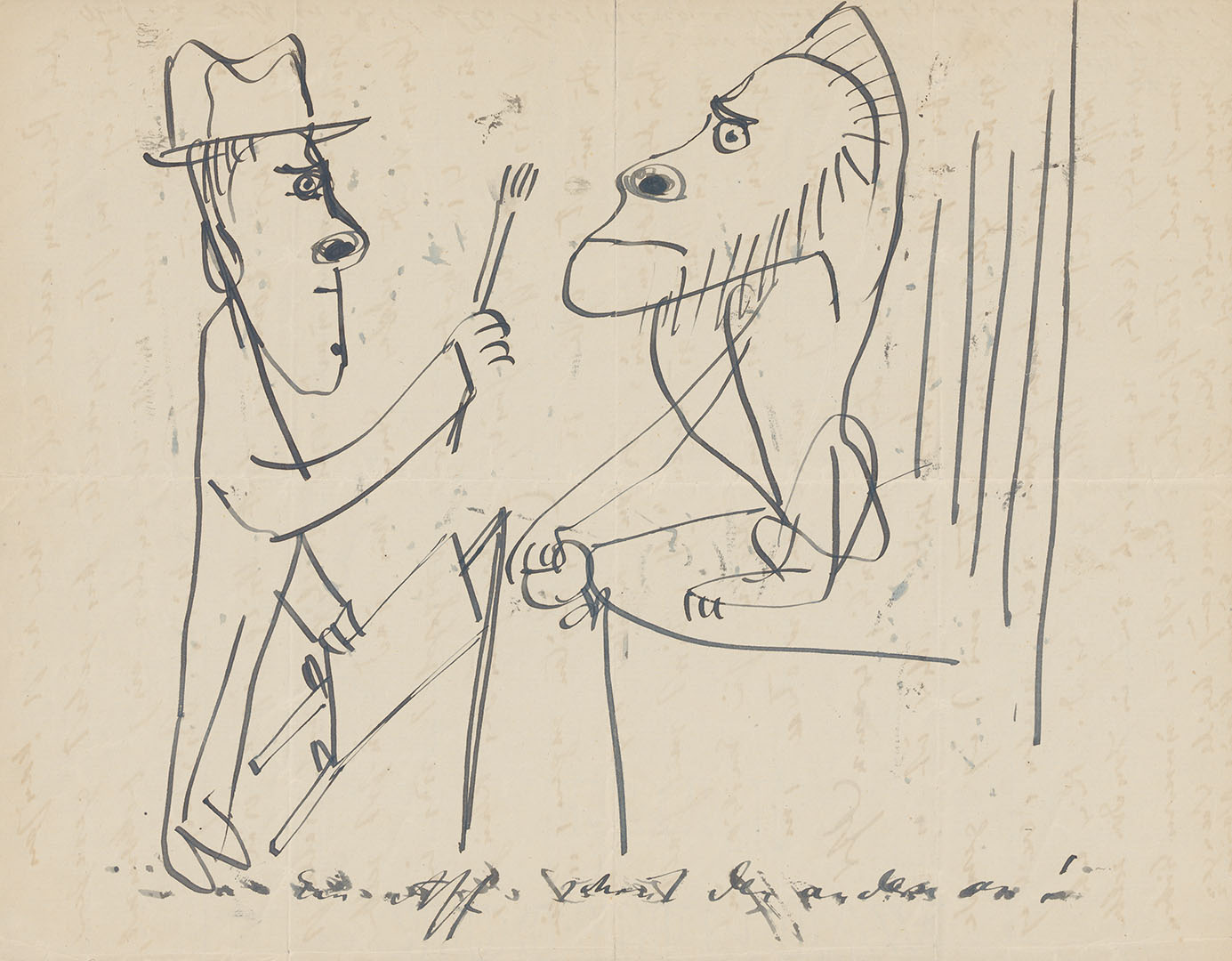

The written works in the estate include notes in Kokoschka’s own hand for essays on art history and politics, lectures, early drafts of his stories and plays, as well as interim versions, reworkings for publishing, unpublished texts and translations.

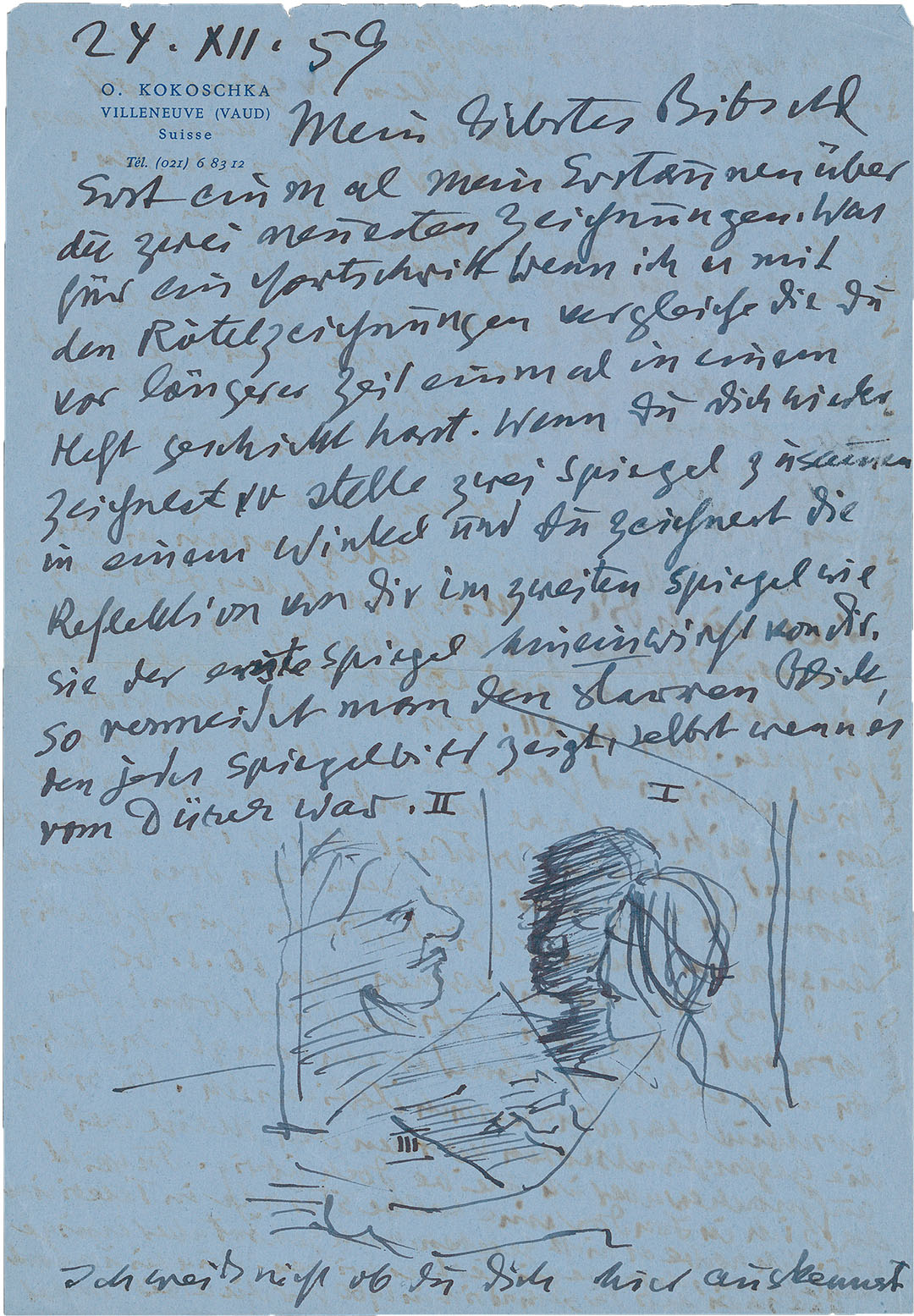

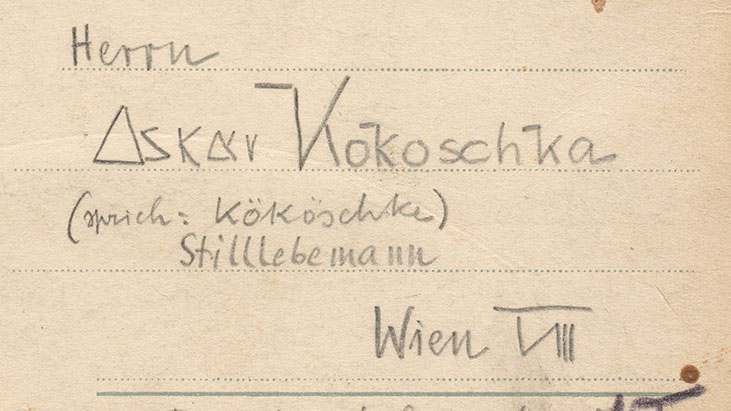

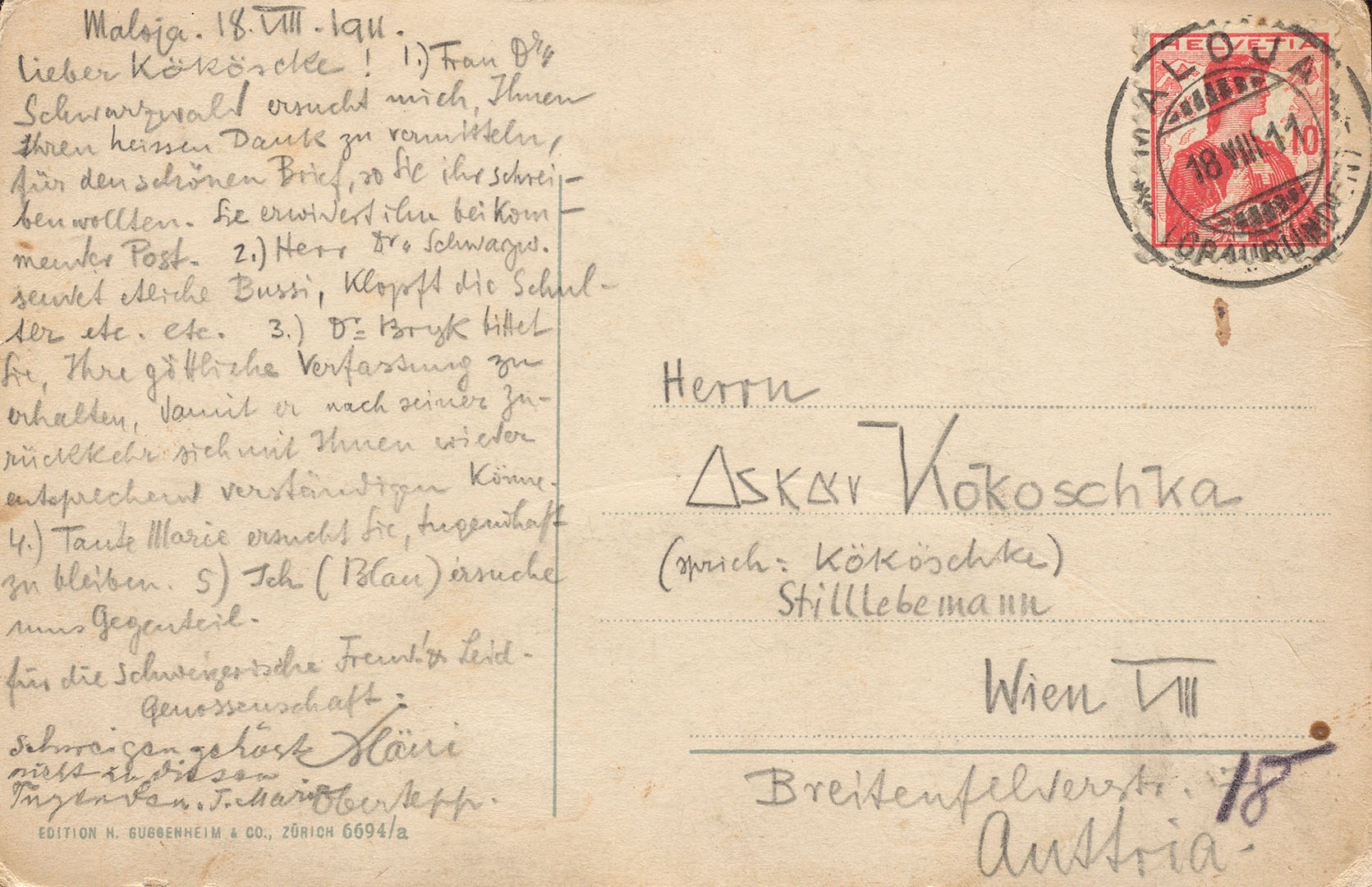

The letter-writer

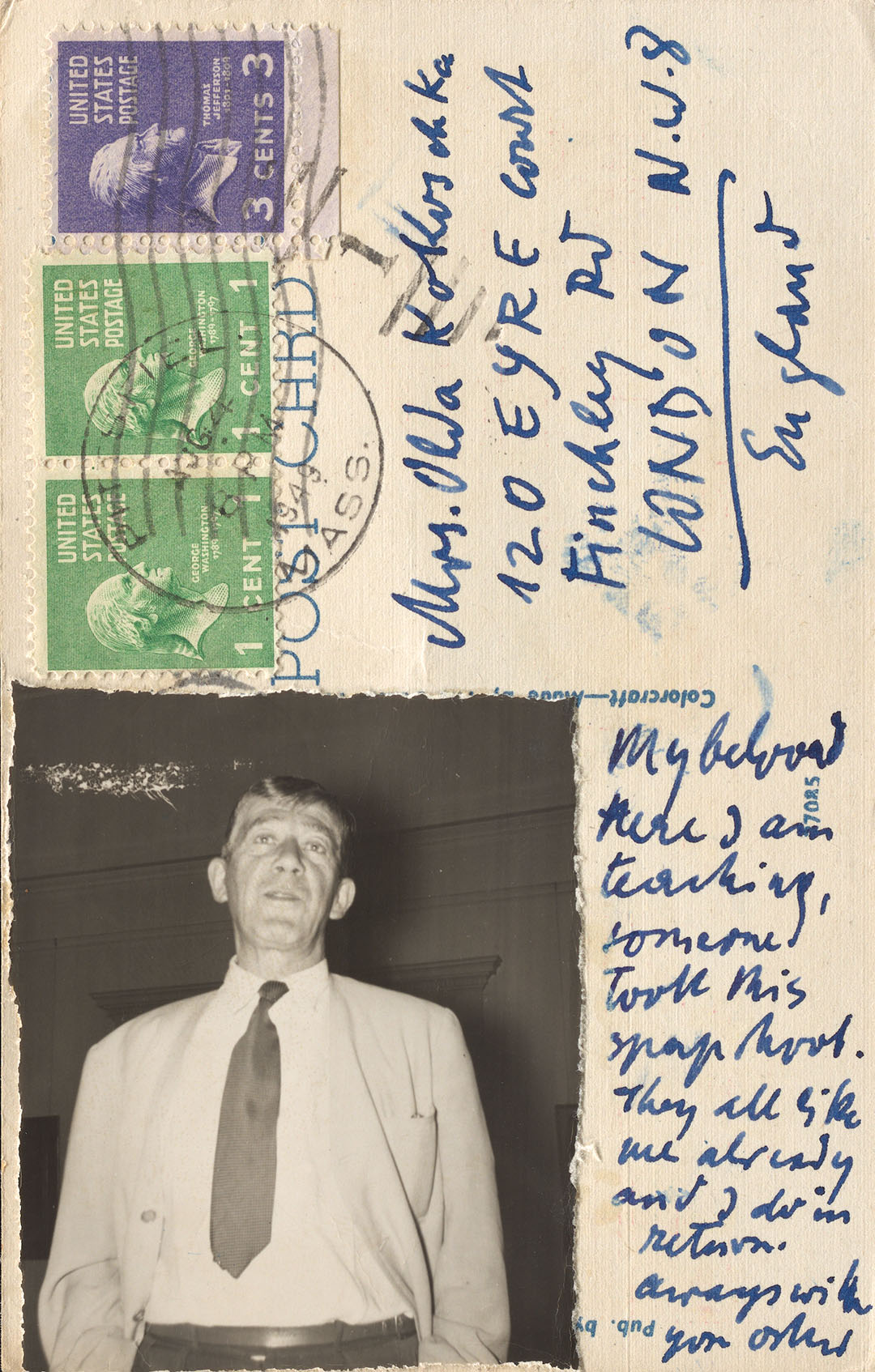

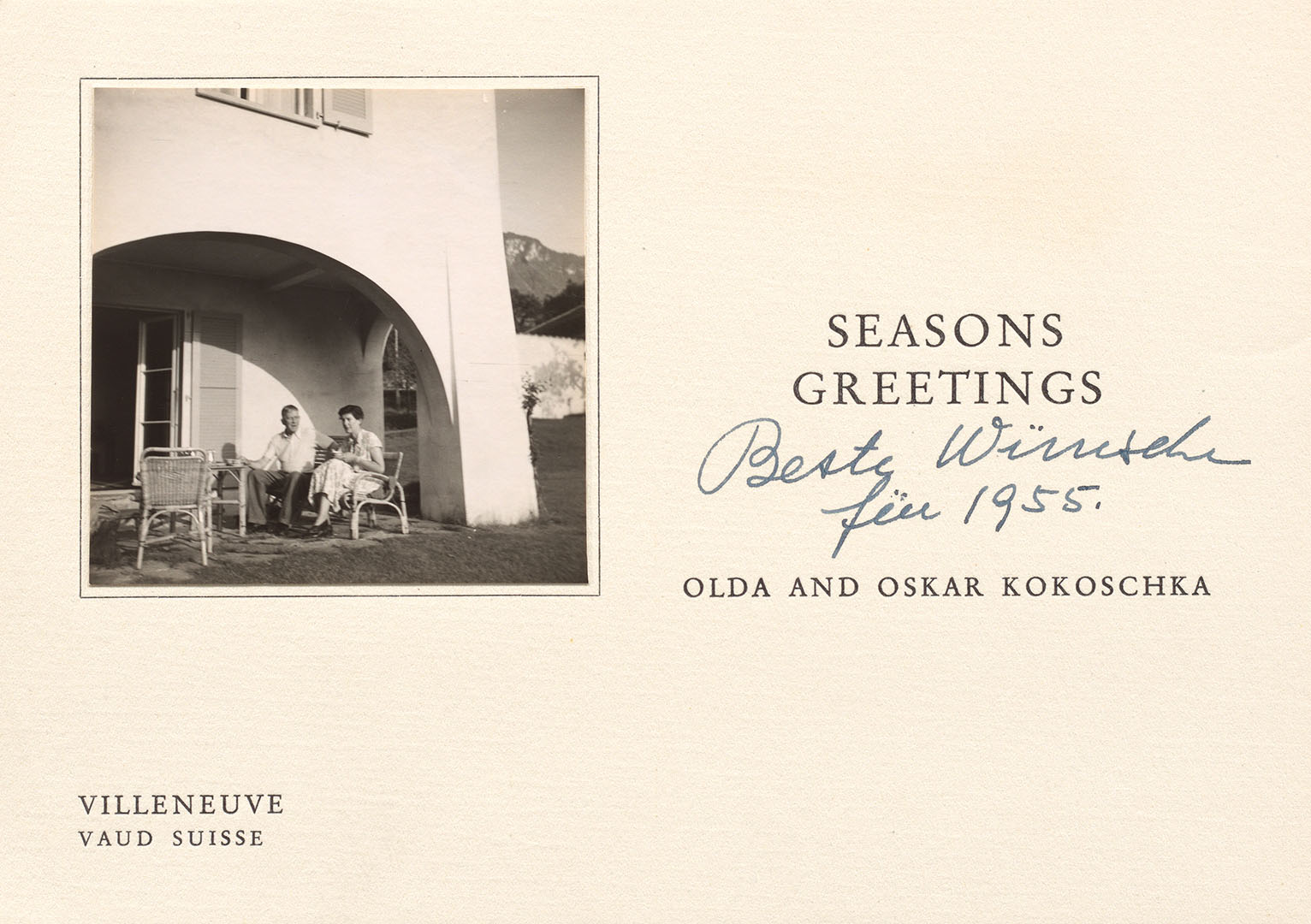

The sheer number of letters to, by and about Oskar and Olda Kokoschka held at the ZB Zürich is astonishing: they number over 25,000, including not only originals but also transcriptions and copies.

Between 1984 and 1988, Olda Kokoschka and Heinz Spielmann published a selection of letters written by Kokoschka in four volumes. Many of the replies entered the ZB with the literary estate.

This vast correspondence is a rich source for research. It covers the entire spectrum of interpersonal communication: from love letters to bitter invective, flirtations with young ladies and euphoric reports together with humorous drawings, business affairs and profoundly personal matters, greetings cards as well as craftsmen’s invoices, visiting cards and receipts.

Oskar Kokoschka and his times: episodes in a life

Oskar Kokoschka was often a little lax when it came to dating things – partly out of carelessness, partly because he wanted to manage his image, claiming that events happened earlier than was actually the case in order to position himself in art history as a precocious genius (for more details, see Régine Bonnefoit).

Biographers working during Kokoschka’s lifetime were hamstrung by the chronological and biographical confusion in his statements. Subsequent research in the literary estate has since resolved many uncertainties.

There are traces of every stage in his rich artistic life at the ZB Zürich.

From chemistry to painting

Oskar Kokoschka is born on 1 March 1886, the second child of Gustav Kokoschka (1840–1923), a goldsmith from Prague, and Romana, née Loidl (1861–1934), in Pöchlarn, Lower Austria. He grows up in impoverished circumstances in Vienna with his younger siblings Berta (1889–1960) and Bohuslav (1892–1976).

There, he attends state schools and initially entertains ideas of becoming a chemist. According to Bohuslav Kokoschka, his mother “pushes him to become an artist rather than a civil servant”; receiving early encouragement from sponsors, however, he takes up painting.

In 1904, the drawing teacher Johann Schober arranges a scholarship for his pupil to attend the Arts and Crafts School in Vienna (now the University of Applied Arts). In summer 1906, he produces his first portraits in oils and the “Lassinger Madonna”.

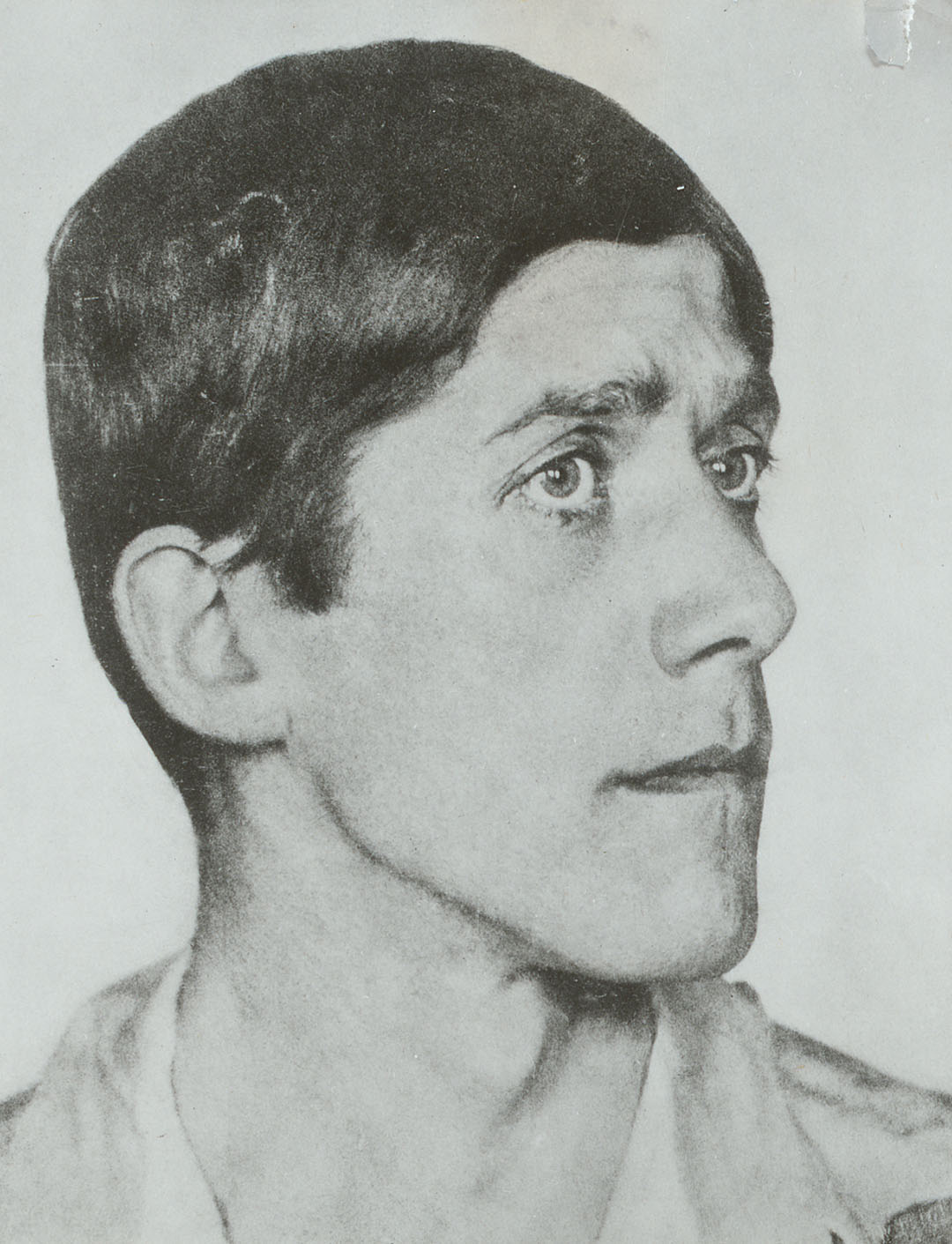

Wiener Werkstätte and theatre scandal

In 1907, as a staff member of the Wiener Werkstätte, the art student Kokoschka illustrates his own poem “The Dreaming Youths” with fairytale colour lithographs.

As both a draughtsman and a playwright, his work is provocative. The première of his one-act play “Murderer, Hope of Women” in July 1909 earns him a reputation as an “angry young man” and “enfant terrible”. He joins the literary circle of Karl Kraus and Peter Altenberg.

Impressed by van Gogh, he seeks out allusive means of expression and emotive ways of applying paint. As well as using a brush to produce his portraits, he also works them with his hands and fingernails, an unconventional method that serves to express the subject’s “inner face”.

Berlin and Vienna

Following his first visit to Switzerland in early 1910, Kokoschka moves temporarily to Berlin and works as an editor of Herwarth Walden’s Expressionist art journal “Sturm”. Berlin gallerist Paul Cassirer stages a first exhibition of his work, including oil paintings, illustrations and nude drawings.

By January 1911, Kokoschka is ready to return to Vienna, where he paints a series of religious images. With the support of friends and patrons, he works as a painter, illustrator, dramatist and drawing teacher, and attracts international attention.

Alma Mahler, war and crisis

In 1914, Kokoschka paints a masterpiece: the dramatically animated double portrait “Bride of the Wind”, now in the Kunstmuseum Basel. It shows him with his lover Alma Mahler. When the musician’s widow puts an end to their tempestuous relationship, Kokoschka volunteers for military service in the 15th Regiment of Royal and Imperial Dragoons.

He is seriously wounded twice, in Galicia and Ukraine. From that moment on, as he writes in the monograph “Kokoschka – Beziehungen zur Schweiz”, he wishes “no longer to be in thrall to any ideologies, national hegemonies or religious orientations”.

The process of spiritual and physical recovery takes a long time. While recovering in the sanatorium at the Weisser Hirsch near Dresden, Kokoschka joins the theatrical circle of Käthe Richter and Walter Hasenclever. A contract with the art dealer Paul Cassirer ensures his financial security until 1930.

Professor Kokoschka in Dresden

Researchers continue to be fascinated by the fact that, in 1918, Kokoschka commissioned the puppet maker Hermine Moos to produce a life-size puppet of Alma Mahler, which was to serve him as both company and model. Art experts have identified in his figural images signs of mental instability, existential angst and isolation.

In 1919, he is appointed professor of art at the Dresden Academy. Paintings of the view from his studio window over Dresden’s new town reveal, according to art historian Norbert Werner, a new “impasto colour fabric structure”. He also creates lithographs and watercolours.

Kokoschka achieves recognition as a painter and author of stage works. His plays “Murderer, Hope of Women” (Paul Hindemith, 1921) and “Orpheus and Eurydice” (Ernst Krenek, 1926) are successfully performed as opera.

The travel years

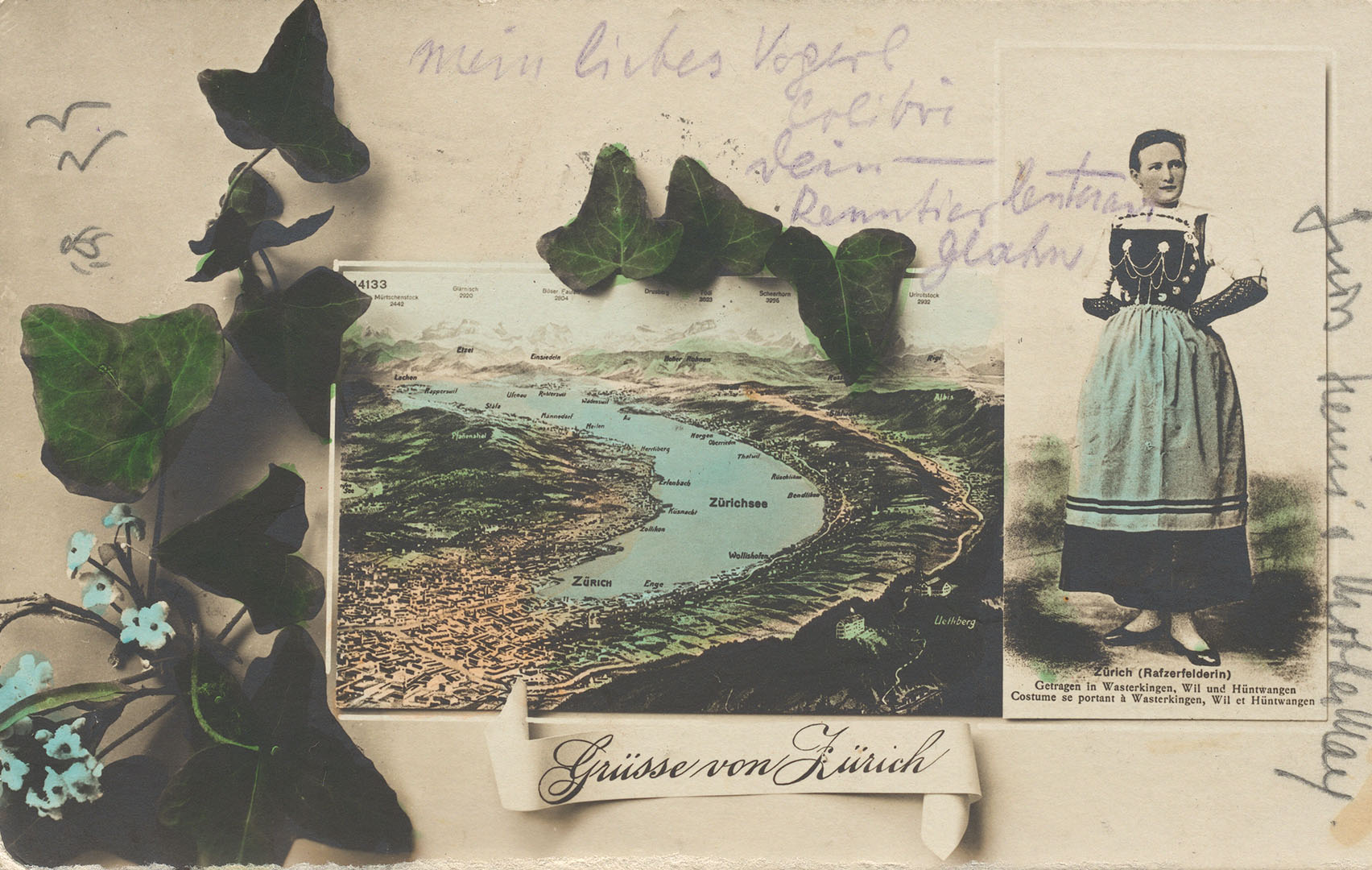

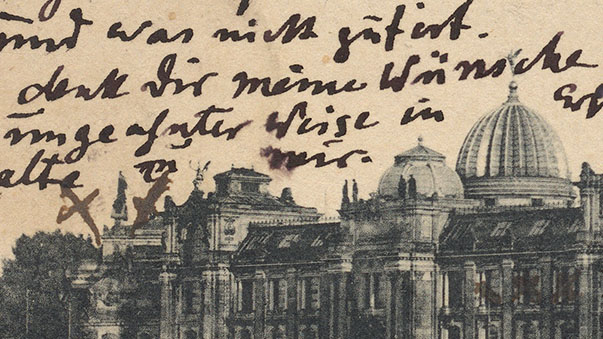

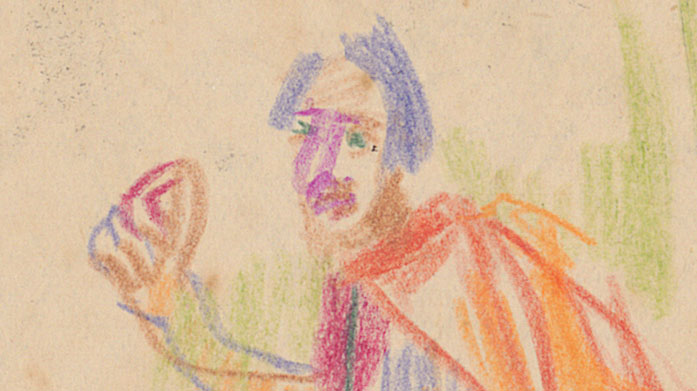

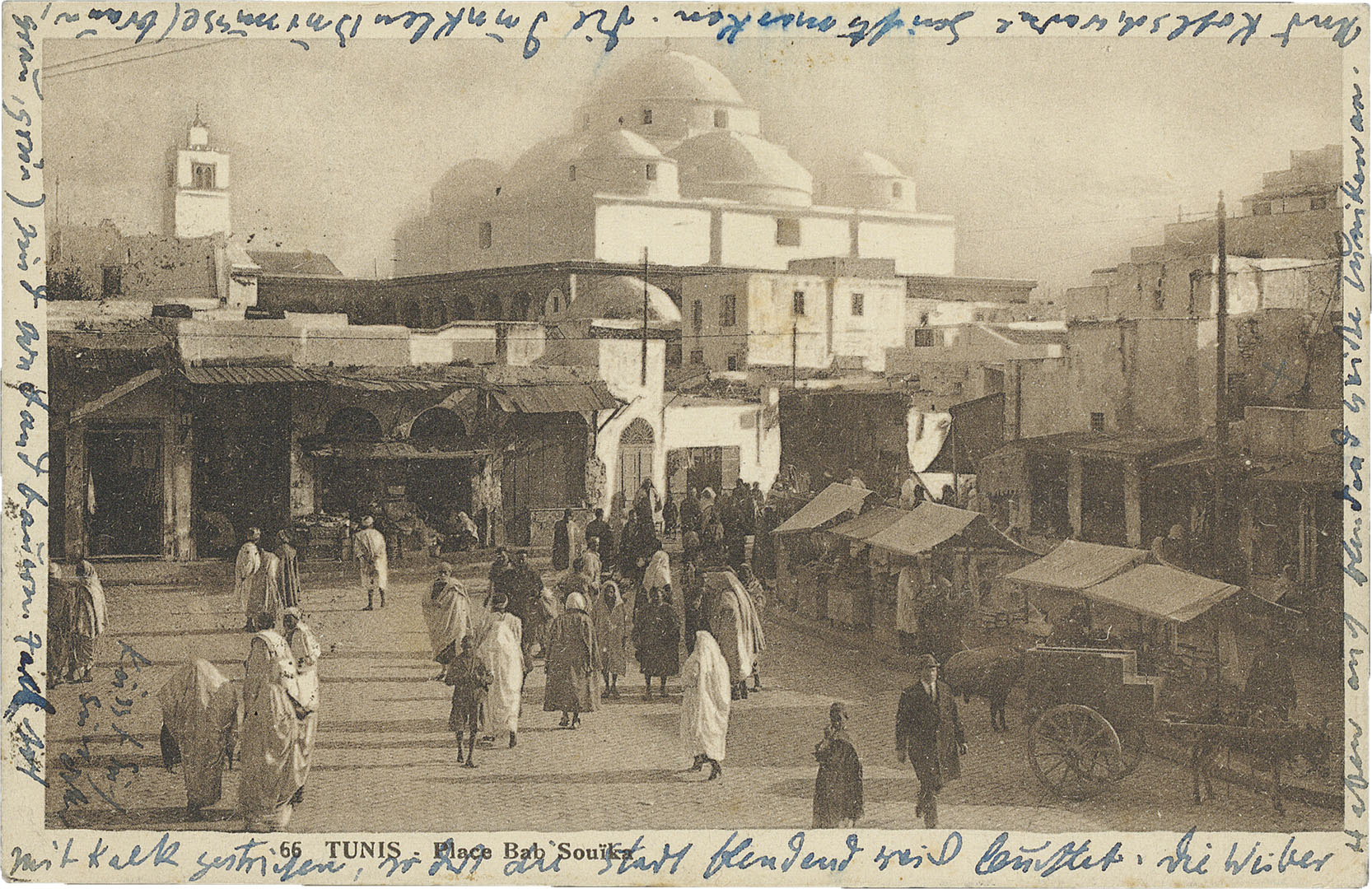

In 1924, Kokoschka develops an urge to travel. He takes leave from work and embarks on extended journeys through Europe as well as the Near East and North Africa. He sends postcards almost every day, updating friends and family about his pictures and route, and reporting on his many and varied impressions of the places he visits – impressions that are reflected directly in his painting.

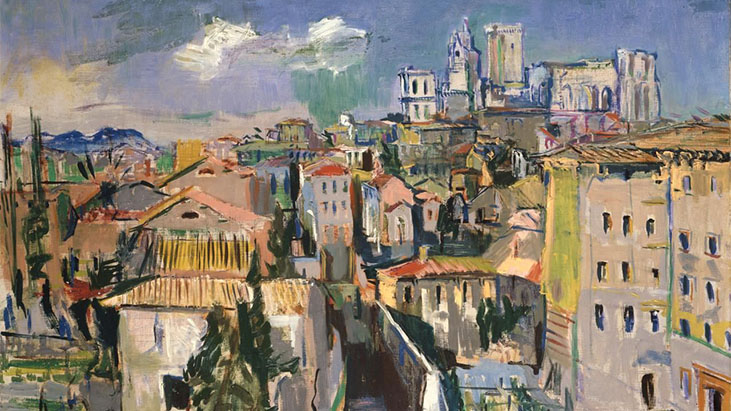

He creates atmospheric cityscapes of Venice, Avignon, London, Lyon, Jerusalem, Istanbul and finally Vienna. They are both his interpretation and his imagination of those places. The Kunsthaus Zürich also exhibits the new series of works in 1935.

Although, by this time, Kokoschka is one of the most prominent painters in Europe, his financial situation deteriorates in the wake of the Great Depression.

A “degenerate” artist in exile in Prague

Under political pressure in Germany and Austria, in 1934 Kokoschka moves to Prague, where his sister Berta Patocka lives and his ancestors had previously. It is here that he meets the woman who is to become his wife: Oldriska Aloisie Palkovska (1915–2004). She holds a doctorate in law.

Kokoschka expounds his critical views of contemporary events. He develops ideas about education reform and writes the drama “Comenius”.

The touring exhibition entitled “Degenerate Art” initiated by Reichsminister Goebbels in 1937, holds Kokoschka’s works up to ridicule. In July, 417 of his pictures are seized from German collections. Nine of them are auctioned in 1939 in Lucerne, including “The Bride of the Wind”.

Exile in England

Following the annexation of Austria and the mobilisation in Czechoslovakia, Kokoschka and Olda Palkovska flee to London in October 1938. “OK has made some beautiful pictures [...], but of course all our future plans collapsed with war and market is practically none now”, she writes to her parents in 1939 from the fishing village of Polperro. In Cornwall and Scotland, Kokoschka produces coloured pencil drawings and lyrical watercolours.

On 15 May 1941, the couple marry in an air-raid shelter in London.

During the war, Kokoschka supports the Allied cause by writing essays, giving speeches and painting allegorical pictures such as “What We Are Fighting For”. He is a co-founder and the president of the anti-fascist Free German League of Culture, and supports aid organisations. Having become Czech citizens in 1938, in 1947 the Kokoschkas exchange this for British citizenship.

The post-war years

It is not until after the Second World War that commissions for portraits from Oskar Kokoschka pick up again. In 1947, he continues his travels around the European continent and also returns to Switzerland. Exhibitions and teaching posts take him back to the US in 1948.

In 1950, he creates his biggest picture in London: the three-part ceiling painting with Baroque echoes entitled “The Prometheus Triptych” measures 2.39 metres by 8.17 metres and breaks “deliberately all the taboos [...] that apply today internationally”.

After visiting the major Munch exhibition in Zurich in 1952, Kokoschka writes for the NZZ newspaper about the Norwegian artist’s symbolic expressionism – and takes a side-swipe at “fashionable non-representational art”.

Final creative years in Villeneuve

Oskar Kokoschka spends the last 27 years of his life in Villeneuve, Vaud. He travels widely, studies Antiquity, Greece, theatre and opera, and finds modern ways of expressing his own experiences and contemporary messages. He argues forcefully for a more humane Europe.

In 1953, along with the art dealer Friedrich Welz, he sets up the international summer academy in Salzburg, where he heads the “School of Seeing” until 1963. In 1955, he launches a second “School of Seeing” in Sion.

In 1974, showered with honours and commissions, he becomes an Austrian citizen once again. He gives up drawing at the end of 1976 due to his failing eyesight. On 22 February 1980, he dies in Montreux Hospital.

Collections and documentation

The estate contains various collections and documentary materials on the Kokoschkas which entered the ZB Zürich in more or less pre-sorted form, such as:

- written works including translations and documents on adaptations and theatre productions

- over 590 travel postcards sent by Kokoschka to his family between 1909 and 1937

- almost 700 art cards that were sent to Kokoschka, arranged by subject

- documentation of works from 1906 to 1973 (integrated into the online catalogue raisonné)

- awards and honours, from honorary membership and the art award to the CBE awarded by Queen Elizabeth II and the Bundesverdienstkreuz

- works by other writers about Kokoschka

Oskar Kokoschka live

Have we awakened your interest in the artist Oskar Kokoschka and the documentation on his life held at the Zentralbibliothek Zürich? Would you like to gain an insight into the world of Kokoschka on site? Estate administrator Monica Seidler-Hux conducts presentations for groups of ten or more on request. Please contact us:

Monica Seidler-Hux

Research aids

Looking for traces of Kokoschka? You can search and browse the literary estate of Oskar und Olda Kokoschka in the archive portal zbcollections.ch and in the manuscript reading room. We have put together an information sheet to help you get started. If you have any questions, please contact the Manuscript Department direct:

Manuscripts

Copyright

This text was compiled by Monica Seidler-Hux, art historian and research assistant in the Manuscript Department, on the basis of the standard literature listed in the research information sheet and from original documents in the estate.

Kokoschka’s work is protected by copyright, which is held by the Fondation Oskar Kokoschka, Vevey / 2021, ProLitteris, Zurich. All forms of reproduction or other use without permission from ProLitteris – with the exception of individual viewing of the works for private purposes – are prohibited. Copyright of the other illustrations (documents, photos) is as indicated in the picture credits.

The ZB Zürich assumes no responsibility for the content of third-party websites that are linked to here.

Monica Seidler-Hux, research assistant in the Manuscript Department

November 2021

Header image: Oskar Kokoschka, “Self-Portrait”, Fiesole 1948 (© Fondation Oskar Kokoschka / 2021, ProLitteris)