Bookmaking – a foray through the history of publishing in Zurich

Publishers straddle the divide between culture and business – two spheres that cannot be easily combined. Nevertheless, courageous book-lovers in Zurich have repeatedly taken the plunge into the world of publishing. A foray through the history of Zurich’s publishing houses shows how closely they are interwoven with intellectual and political history.

Internationally renowned printer-publishers

A text on indulgences, published in 1479, was the first book printed in Zurich. Almost thirty years later, the first illustrated book was printed in the city: a perpetual calendar with colourful pictures and decorations.

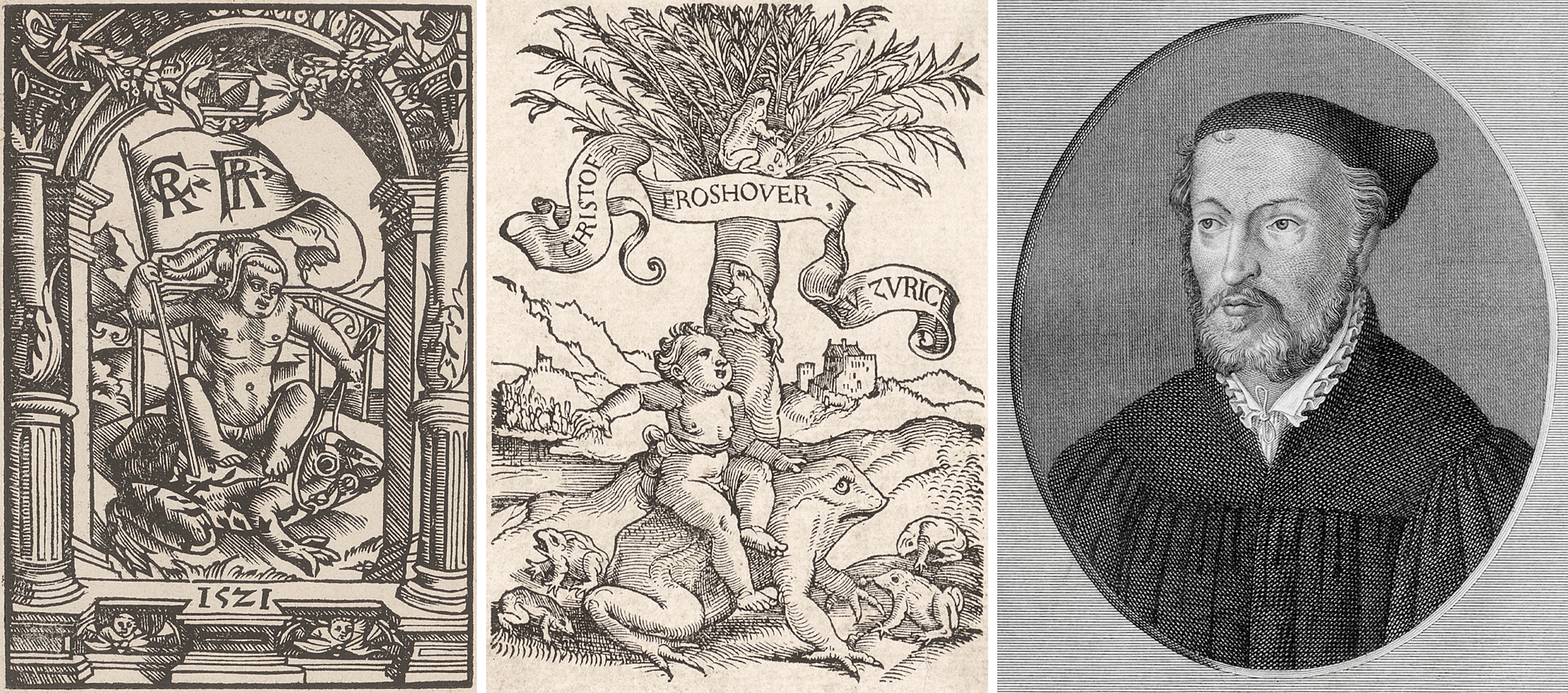

The Reformation saw Zurich’s book printing industry truly come into bloom for the first time, as authors sought to disseminate controversial publications. Alongside Basel and Geneva, the city thus developed into a major hub of book printing in Switzerland. Christoph Froschauer seized the opportunity: his printing house was soon the dominant force in Zurich and he made a name for himself far beyond the borders of the country.

The Enlightenment brought with it a second peak for publishers. Well-known figures such as Johann Jakob Bodmer, Johann Jakob Breitinger, Salomon Gessner and Johann Caspar Lavater made Zurich the most important place in Switzerland for the industry, particularly due to the Orell Füssli publishing house. Throughout Europe, the city was viewed as ‘Athens on the Limmat’. However, the political unrest around the turn of the 19th century saw its international renown disappear once again.

Literature in exile and pacifism on the Limmatquai: Rascher Verlag

In the 19th century, Swiss-German authors such as Gottfried Keller, Conrad Ferdinand Meyer, Johanna Spyri and Robert Walser mainly had their works printed by German publishers. At the beginning of the 20th century, however, the publishing house Rascher & Co. was founded in Zurich – marking a major milestone.

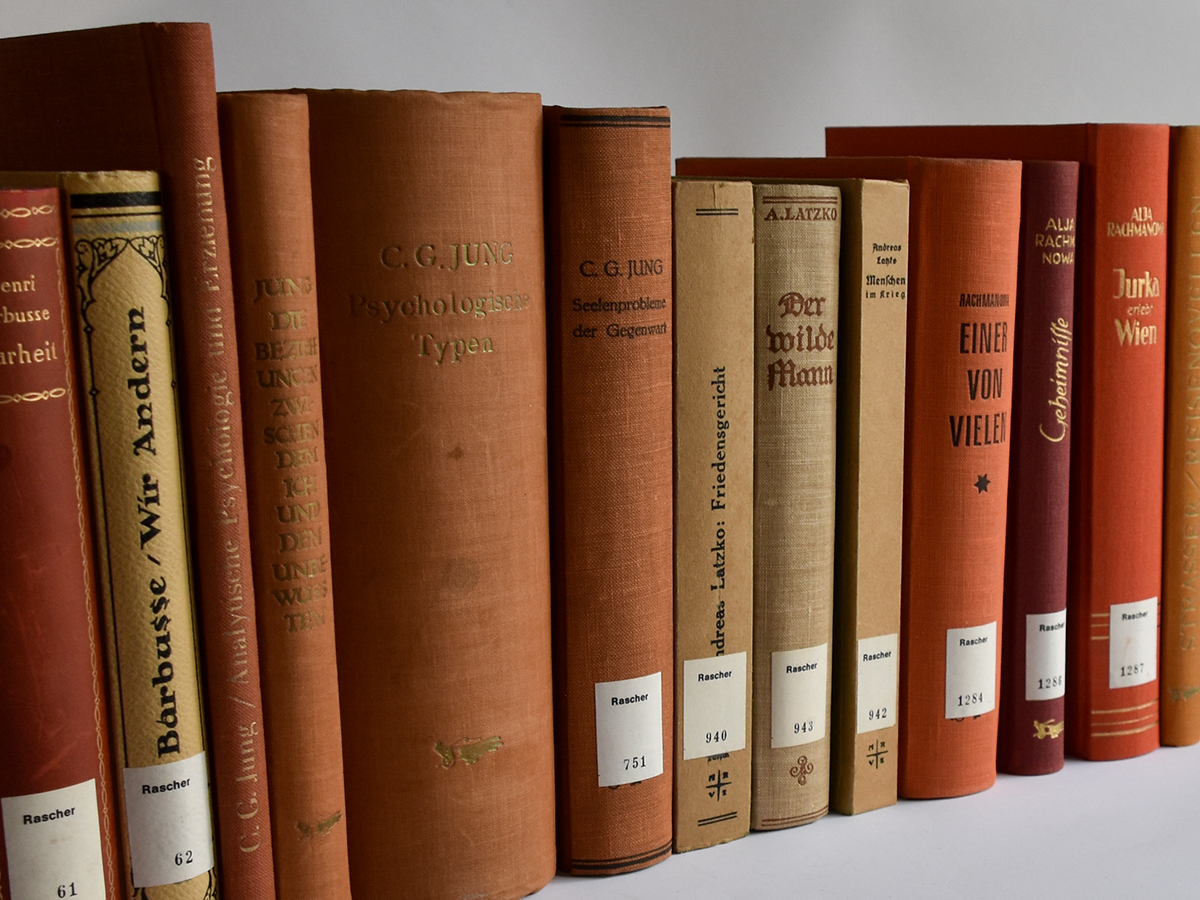

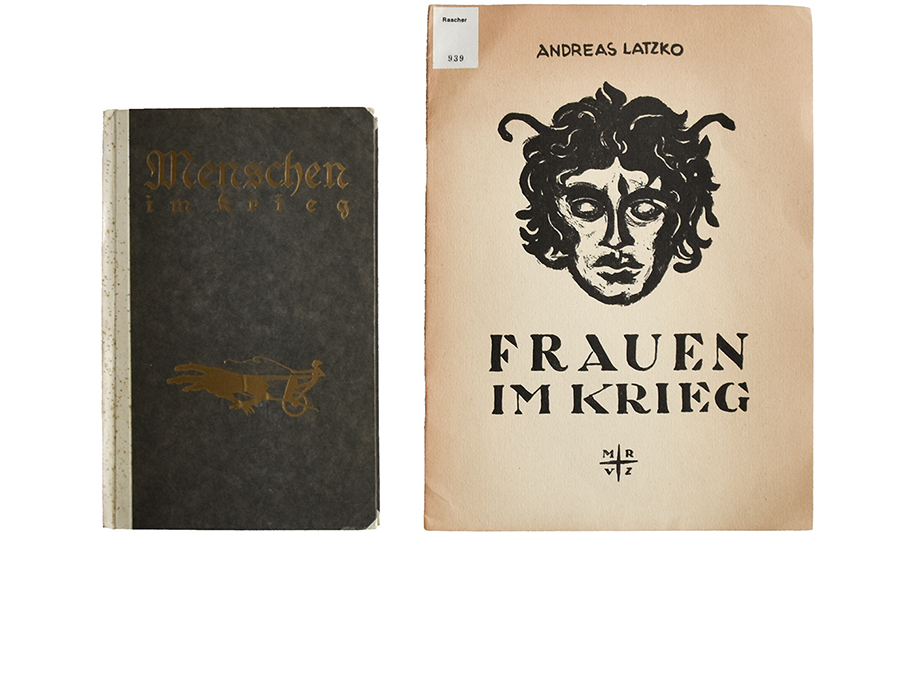

The First World War was a challenging time for book production in Germany: paper became scarce and the public’s purchasing power dwindled. Swiss publishers found it was no longer worth exporting their wares, and only a few publishers published more titles than in the pre-war period. One of them was Max Rascher.

He offered a platform for poets, painters and intellectuals who had emigrated. Most of the writings he published were pacifist treatises, but they also included works on psychology and art. By publishing exile literature and anti-war books, Rascher risked being expelled from the ‘Börsenverein der Deutschen Buchhändler’ (‘Association of German Booksellers’), a powerful organisation in the German-language publishing industry.

Intellectual national defence on paper – and, once again, literature in exile

German publishers once again dominated the Swiss book market during the 1920s and Switzerland continued to have close cultural ties with its neighbour. This changed in 1933 when the National Socialists seized power.

In this year, an article in the ‘Anzeiger für den Schweizerischen Buchhandel’ (‘Swiss Booksellers’ Gazette’) called for the intellectual defence of the country, which the author also (and especially) saw as the responsibility of the book industry. In 1934, booksellers and publishers developed a new strategy to promote Swiss books. A general meeting of the industry took place in 1939, symbolically held as part of the Swiss National Exhibition in Zurich.

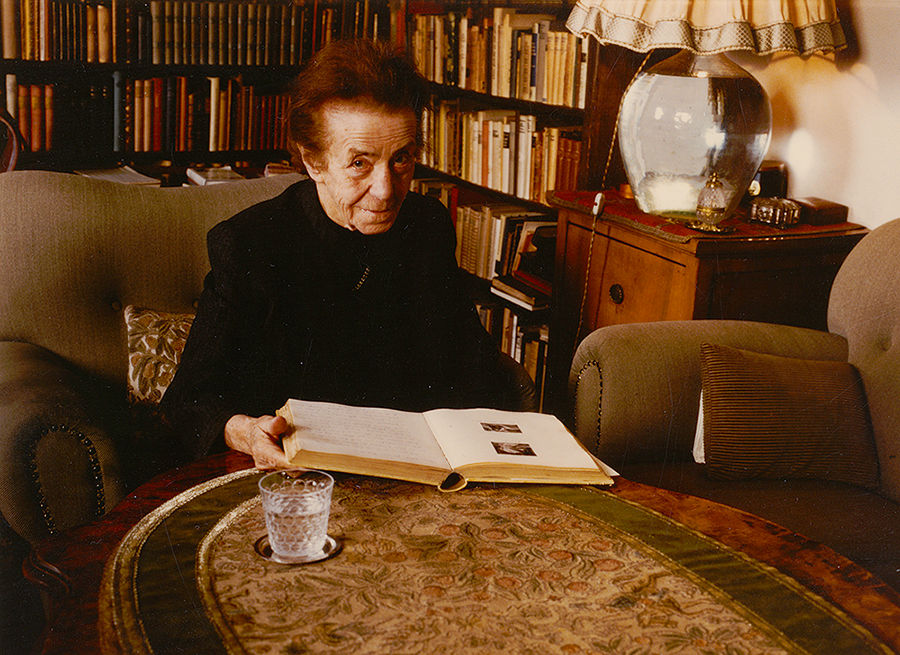

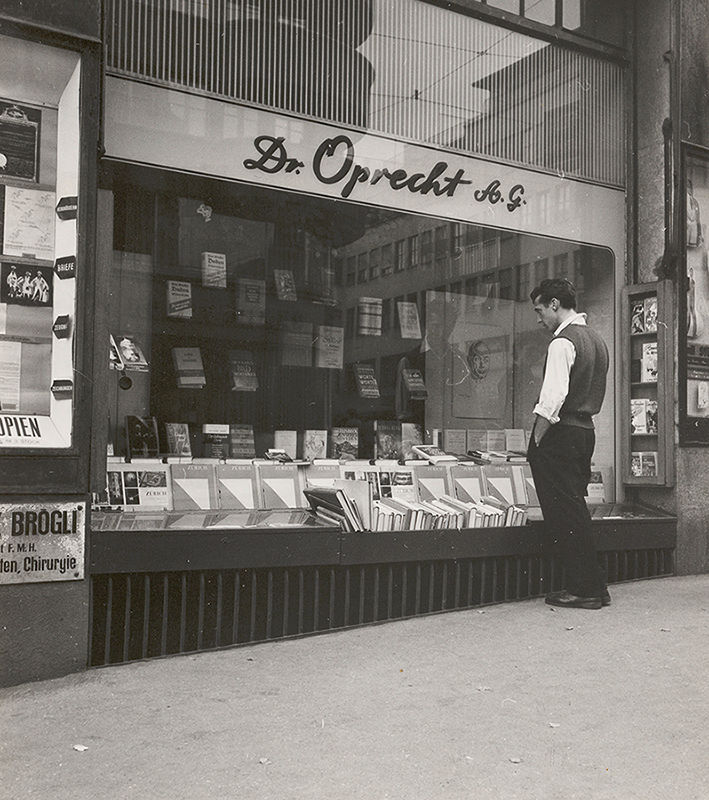

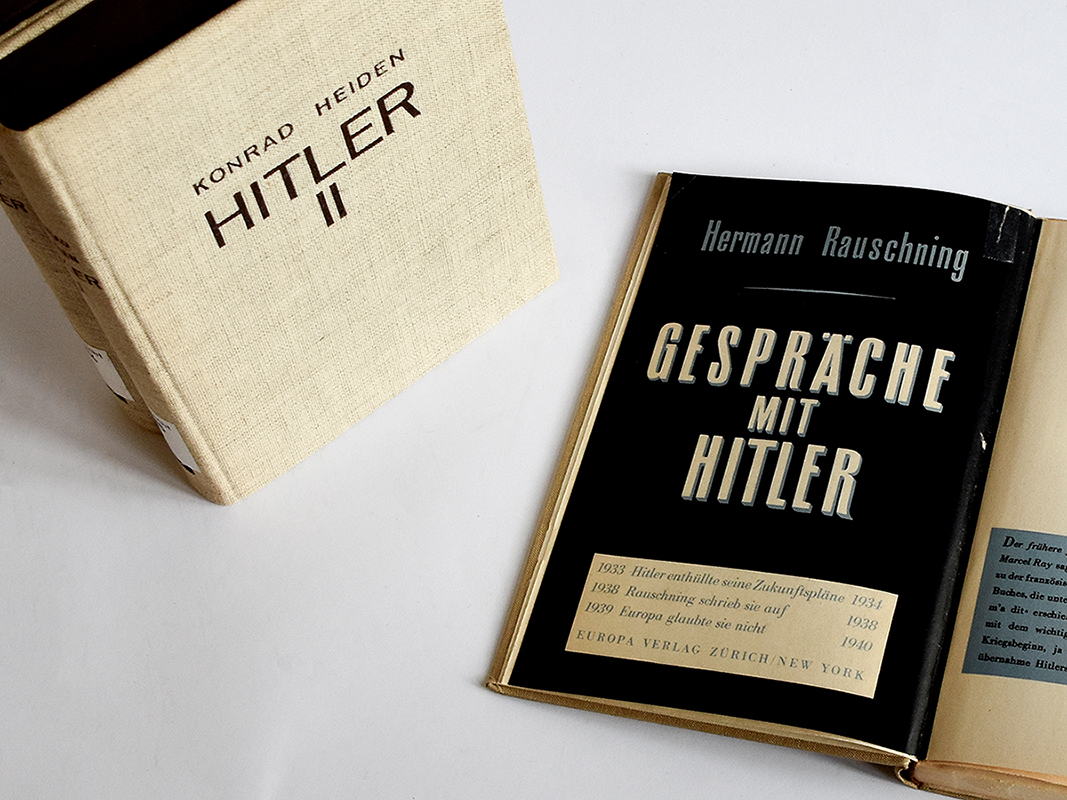

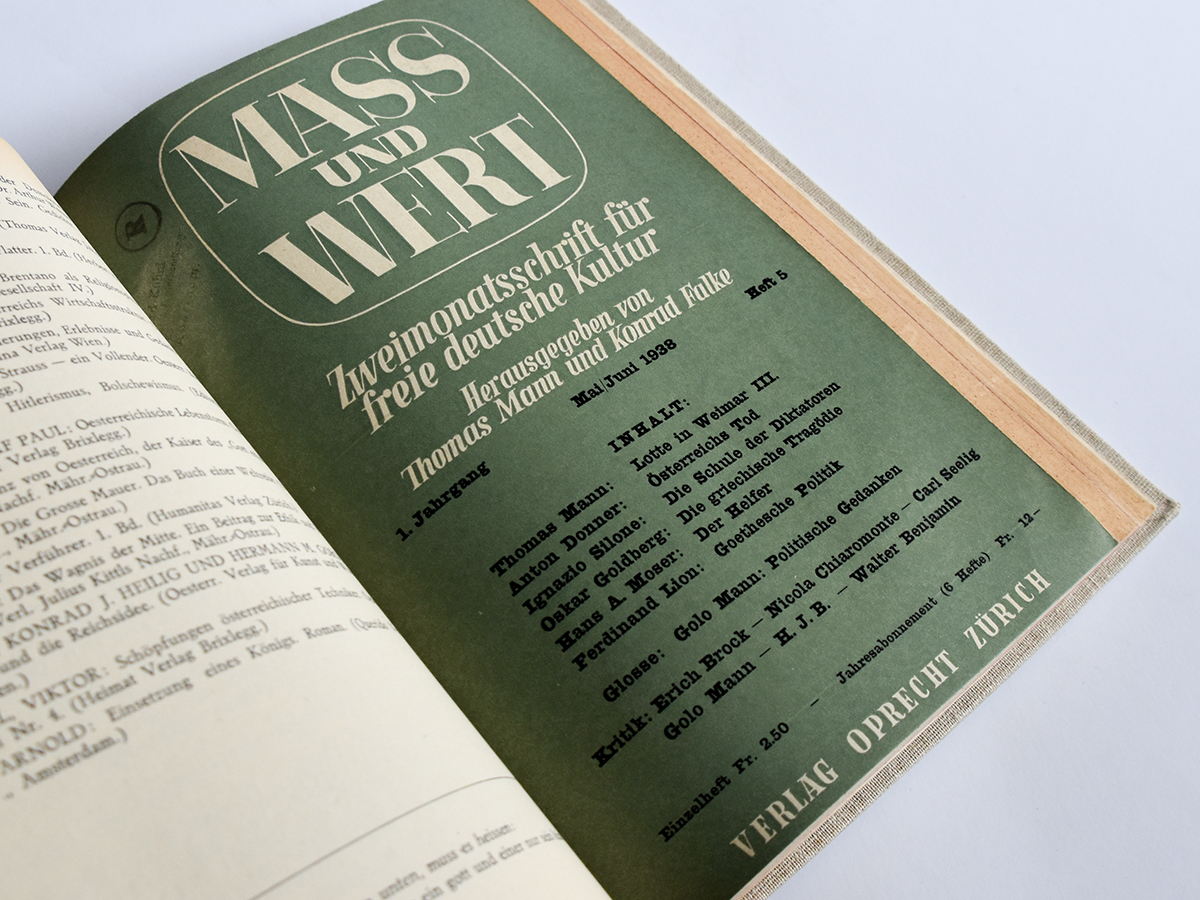

In parallel with this strong national focus, persecuted authors once again began to publish their works in Switzerland. The most important Swiss publisher of works by authors in exile was Emil Oprecht with his Oprecht Verlag and Europa Verlag, which mainly published critical writings on the subject of fascism. As the Deutsche Börsenverein increasingly became a tool with which the National Socialists wielded their power, Oprecht was excluded from membership.

The ‘golden hour of bookselling in Switzerland’

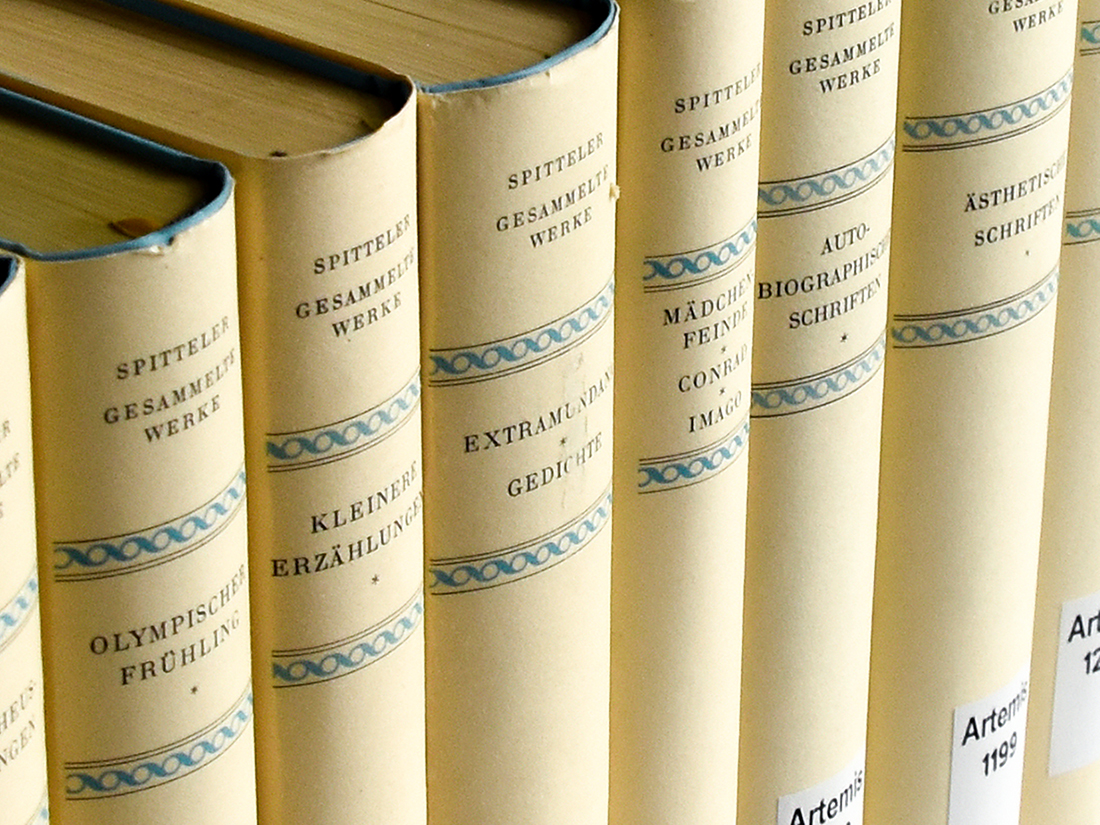

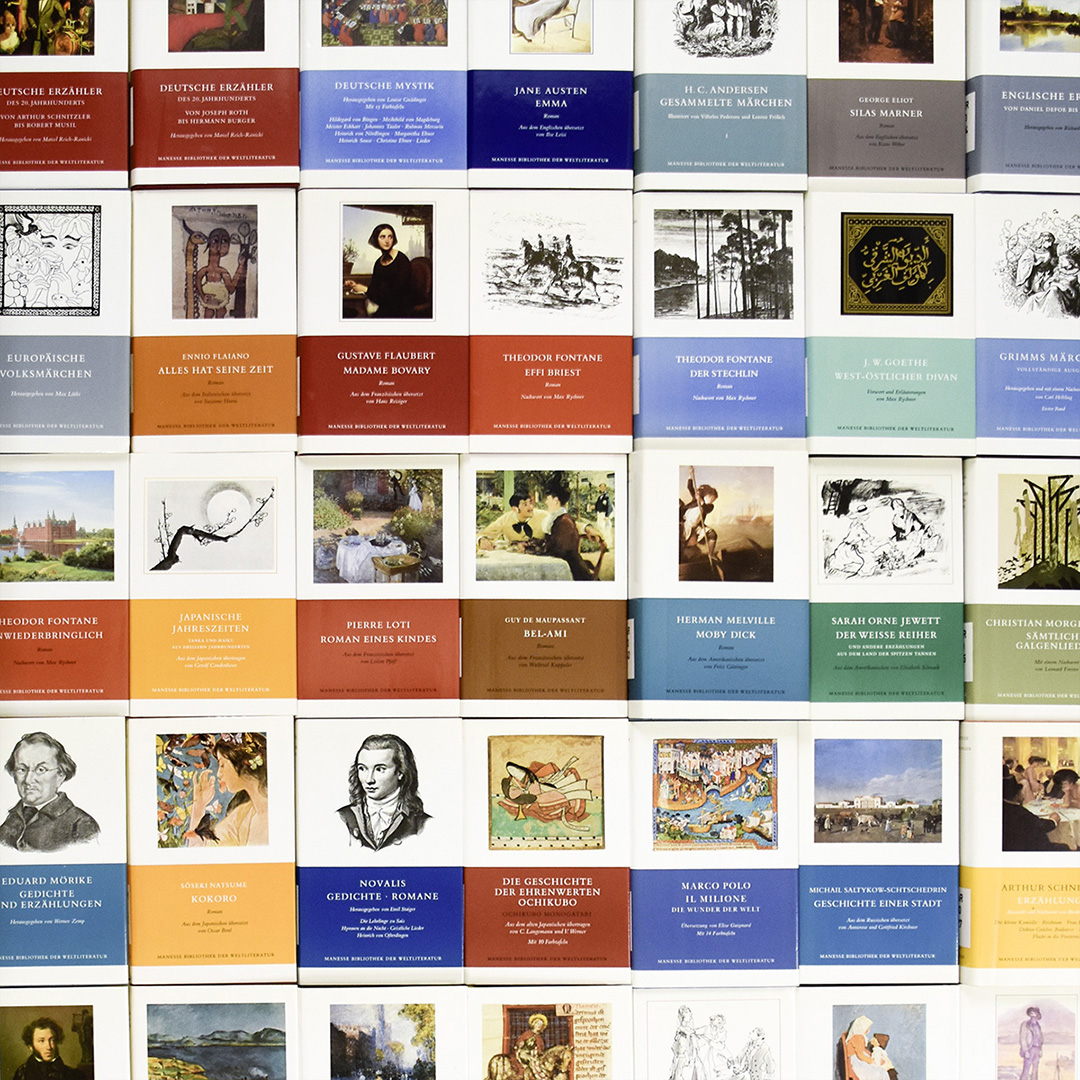

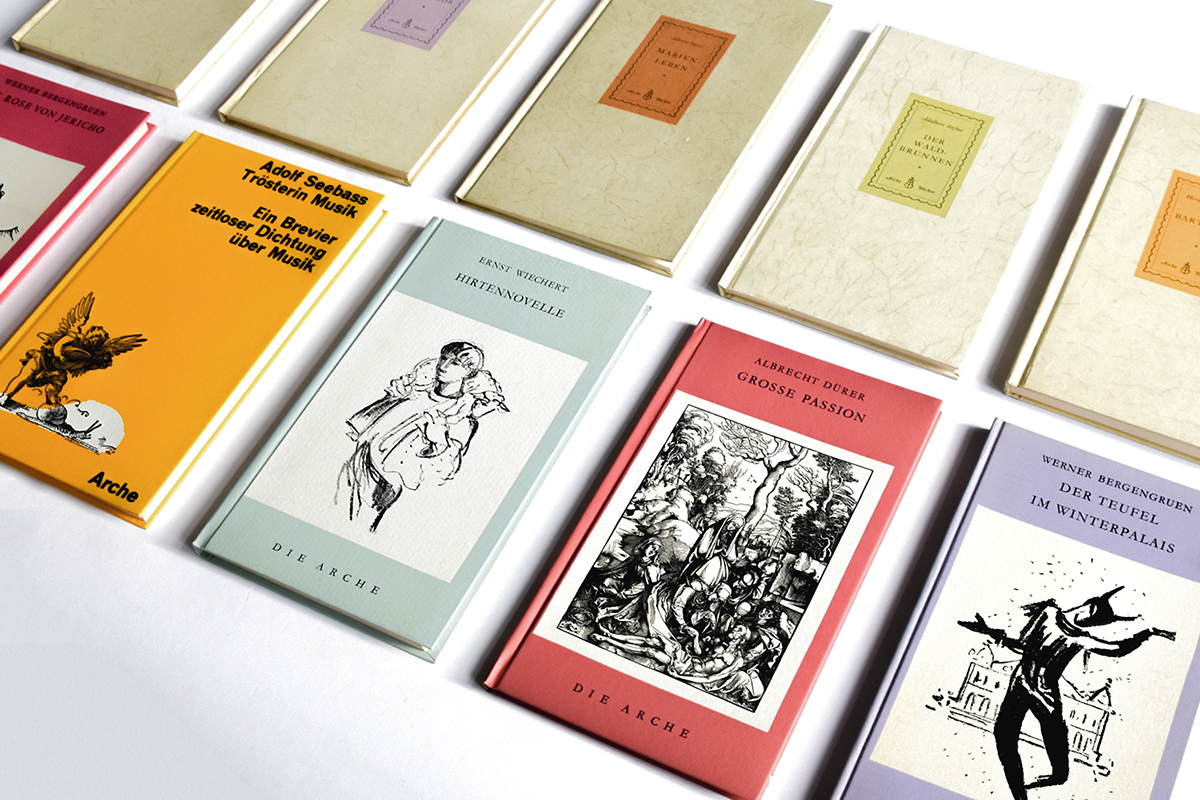

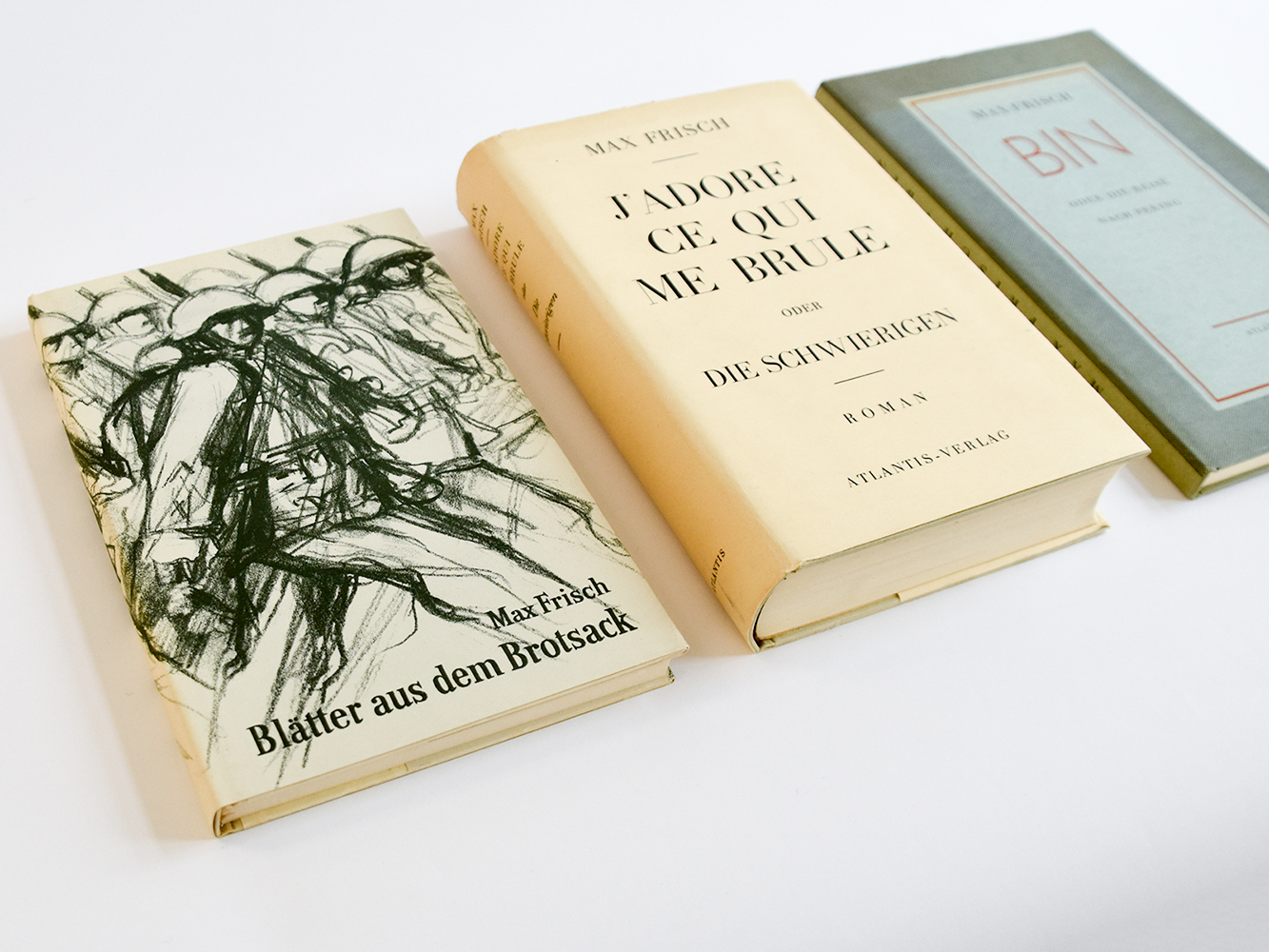

The Swiss publishing industry prospered after the Nazis seized power – and the post-war period promised further growth, with countless new publishing houses established from 1943 onwards. In Zurich, Friedrich Witz founded Artemis Verlag, Peter Schifferli set up Die Arche and Walther Meier established Manesse Verlag. Atlantis Verlag was also based in Zurich at the time: due to the political situation, Martin and Bettina Hürlimann had moved their headquarters here.

In addition, the Federal Council took protectionist steps by adopting a resolution entitled ‘Protecting the Swiss Publishing Houses from the Excess Influence of Foreign Nationals’ (‘Schutz des schweizerischen Buchverlags gegen Überfremdung’). The aim was to prevent German citizens from buying up Swiss publishing houses in order to publish works from Switzerland after Germany had collapsed.

In the post-war period, Swiss publishers had untold opportunities to gain a foothold on the international stage. However, they were unable to seize their chance and restricted themselves to the national arena. The ‘golden hour of bookselling in Switzerland’ was soon over.

Turbulent times

During the 1950s and 1960s, up-and-coming publishers such as the Zurich-based Diogenes Verlag, founded in 1952, gave light fiction a permanent place in their programmes. In doing so, they turned away from elitist educational aims, with the importance of politically left-wing publishing houses, such as Europa Verlag, diminishing.

The 1968 movement saw bourgeois culture become even more unstable and the publishing landscape changed. Countless new, small publishing houses with socially critical programmes were set up; this wave did not abate even after the Opera House riot. Publishers reflected and influenced a society that was changing and becoming more diverse. Here are some of the Zurich-based publishing houses that emerged as part of this wave.

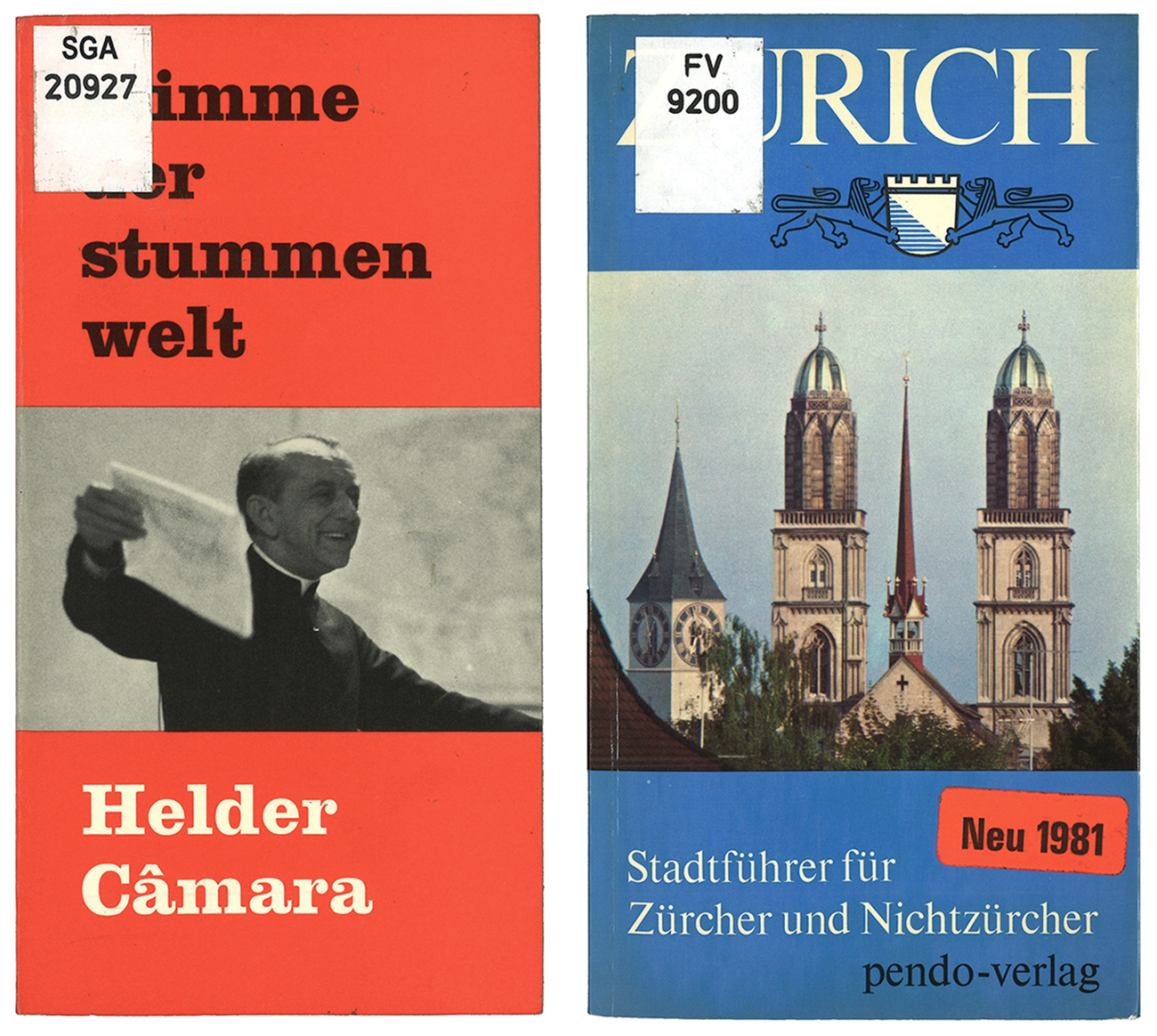

Pendo Verlag

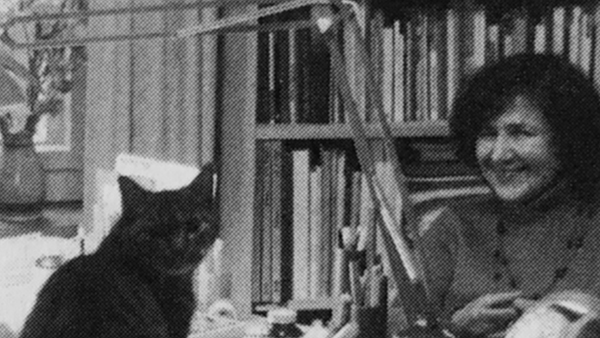

Journalist Gladys Weigner and photographer Bernhard Moosbrugger founded Pendo Verlag because of – and with – their own report: in 1971, they published the book Stimme der stummen Welt (Voice of the Silent World) about a Brazilian archbishop. Pendo means ‘common understanding’ or ‘love’, and their commitment to cultural understanding was reflected in their publishing programme.

In addition to non-fiction, Weigner and Moosbrugger published illustrated books, fiction and poetry. They also edited various book series, including ‘pendo-zürich’, with its multi-award-winning Stadtführer für Zürcher und Nichtzürcher (City Guide for Zurich Residents and Non-Residents).

The founders stepped away from the publishing house at the end of the 1990s. After several changes of ownership, Pendo is now part of the entertainment section at Munich-based Piper Verlag; the notion of common understanding has been lost.

![The duo behind Pendo Verlag – Bernhard Moosbrugger and Gladys Weigner – in the 1980s with tomcat Kater Murr. (Image: anonymous/from ‘Bernhard Moosbrugger – Fotograf und Verleger’ [‘Bernhard Moosbrugger – Photographer and Publisher’])](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/zuerich/Zuercher_Verlage/20240304-TUR-Zuerich-Verlage-05-1-1.jpg)

Limmat Verlag

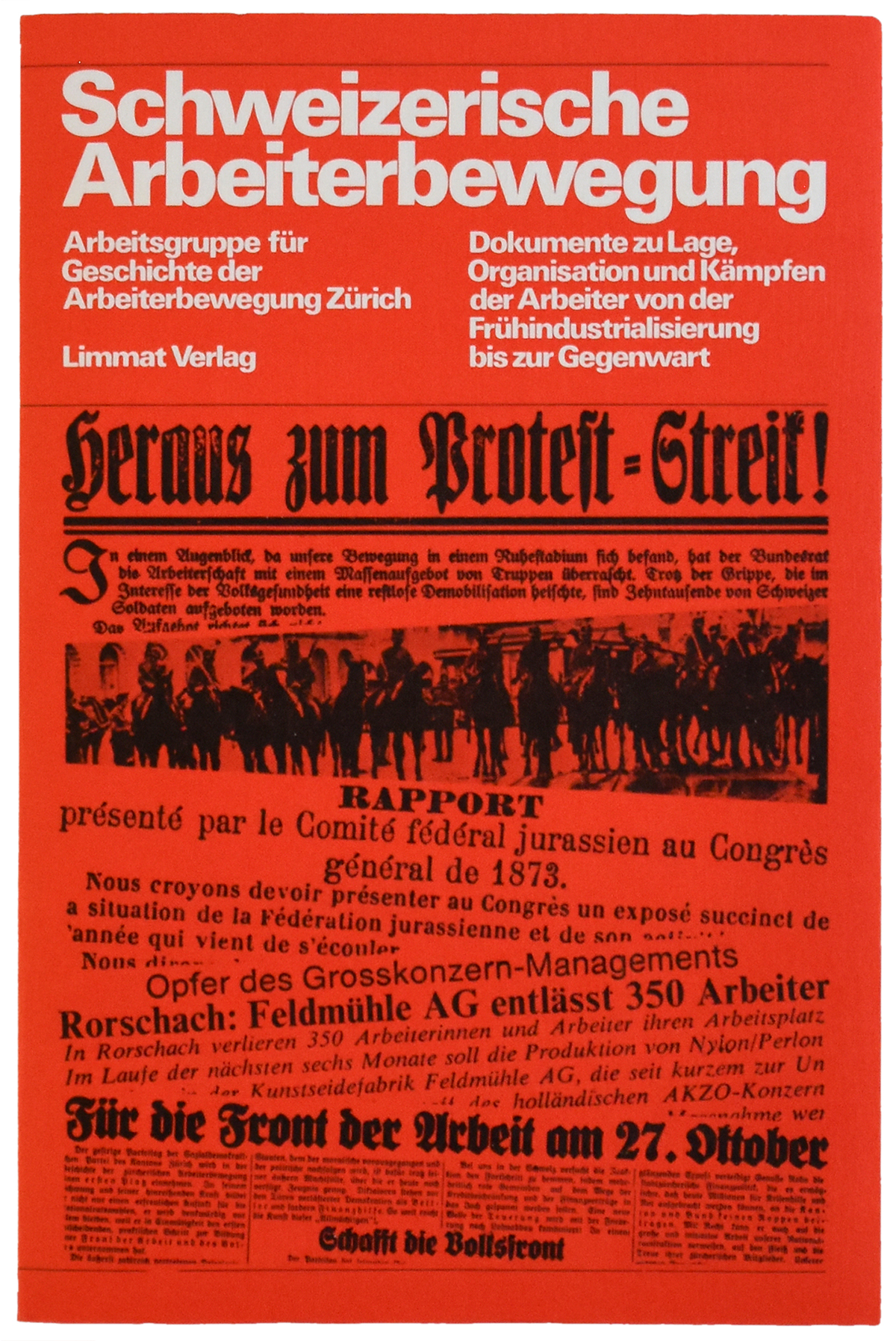

An exhibition on the history of the Swiss labour movement marked the beginnings of Limmat Verlag. It was not permitted for the documentary volume to be released by two publishers, and so it was published in 1975 by Limmat Verlag, which was founded especially for this purpose. The publishing house, which was organised as a cooperative and grassroots democracy at the time, soon began releasing more books.

Its publishing programme still includes political non-fiction to this day. Titles such as Die unheimlichen Patrioten (The Uncanny Patriots), Sniffelstaat Schweiz (The Swiss Snooping State) and Frauengeschichte(n) (Women’s History and Stories) attracted renown, while its literary programme included books by Laure Wyss, Isolde Schaad and Niklaus Meienberg. Max Frisch’s last book was also published by Limmat Verlag. Biographies and autobiographies are another focus of its programme.

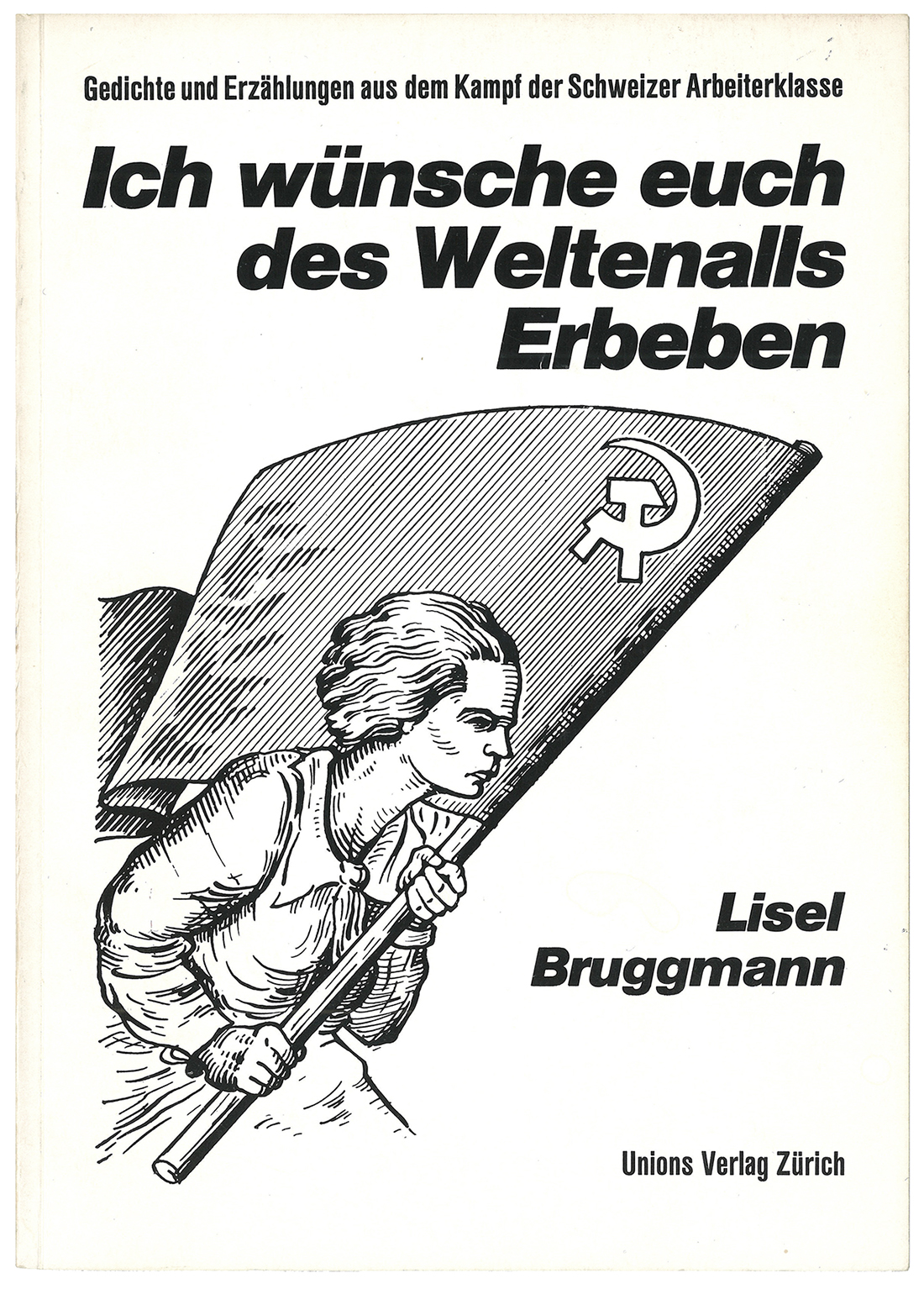

Unionsverlag

The history of Unionsverlag, another left-wing publishing house, also began in 1975. Unionsverlag was founded at a kitchen table with CHF 2,000, plenty of idealism and zero publishing experience.

From these brave beginnings, it has evolved into a firm fixture of Zurich’s publishing industry. Unionsverlag soon brought a cosmopolitan touch to Zurich with its international fiction. ‘We want people to read books and then understand the outside world and the people there better,’ publisher Lucien Leithhess explained to WOZ, describing the idea behind the programme.

Unionsverlag has recently found a wonderful new home under the banner of the publishing group C.H. Beck in Munich, its future seems secure, but, at the same time, Unionsverlag is to remain independent within this overarching framework.

Rotpunktverlag

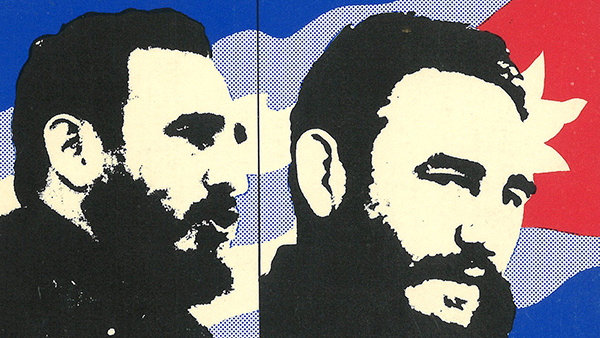

The communist-oriented ‘Progressive Organisationen der Schweiz’ (‘Progressive Organisations of Switzerland’, POCH) founded Rotpunkt Verlag in 1976. Its first book was Fidel Castro’s ‘Ausgewählte Reden zur internationalen Politik 1965–1976’ (‘Selected Speeches on International Politics 1965–1976’) and Walter Andreas Diggelmann’s controversial novel Ich heisse Thomy (My name is Thomy). A collective decided on the publisher’s programme.

In the 1990s, the voluntary political project became a publishing house with salaried staff and a well thought-out approach to book design. Its range of political non-fiction and primarily, but not exclusively, Latin American fiction was supplemented by books on hiking.

The publishing house managed to make it into the new millennium. When the founding generation withdrew in 2017, it subtly reinvented itself without losing sight of its own roots.

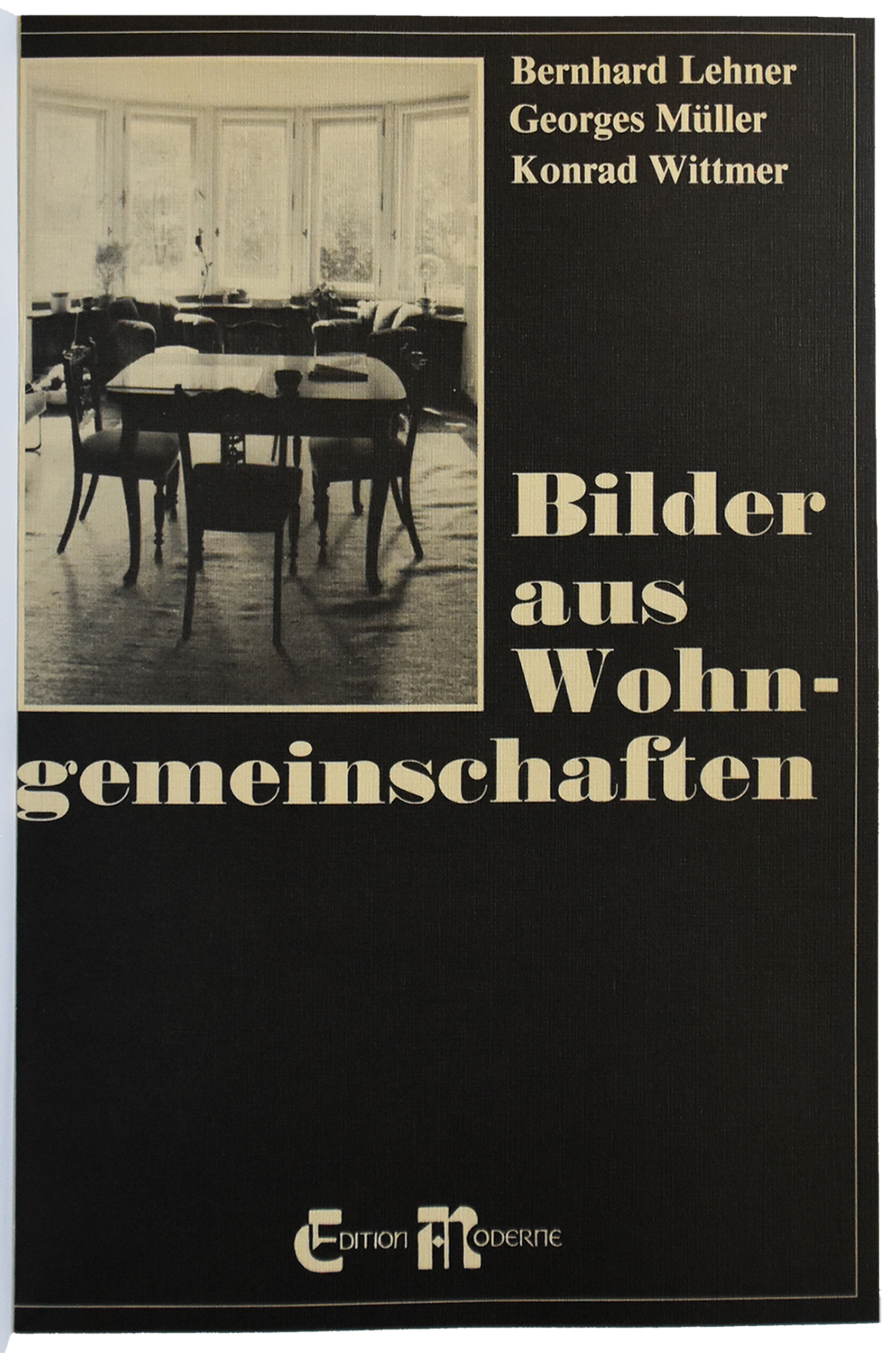

Edition Moderne

Today, Edition Moderne is known as a publisher of comics and graphic novels. However, it all started with the photo book Bilder aus Wohngemeinschaften (Images from Residential Communities), followed by fiction and comics. Its first bestseller was s’Knüslis in 1987. Edition Moderne has solely published comics since 1989, and it has been able to pay its staff a wage since the success of Zürich by Mike in the late 1990s.

The Edition Moderne office ‘almost functions like a flat share – just like I’ve always wanted it to be,’ long-standing publisher and co-founder David Balser told the NZZ at the turn of the millennium.

The next generation of publishers has been leading Edition Moderne into the future since 2019. It’s still indie, but now bears a new look.

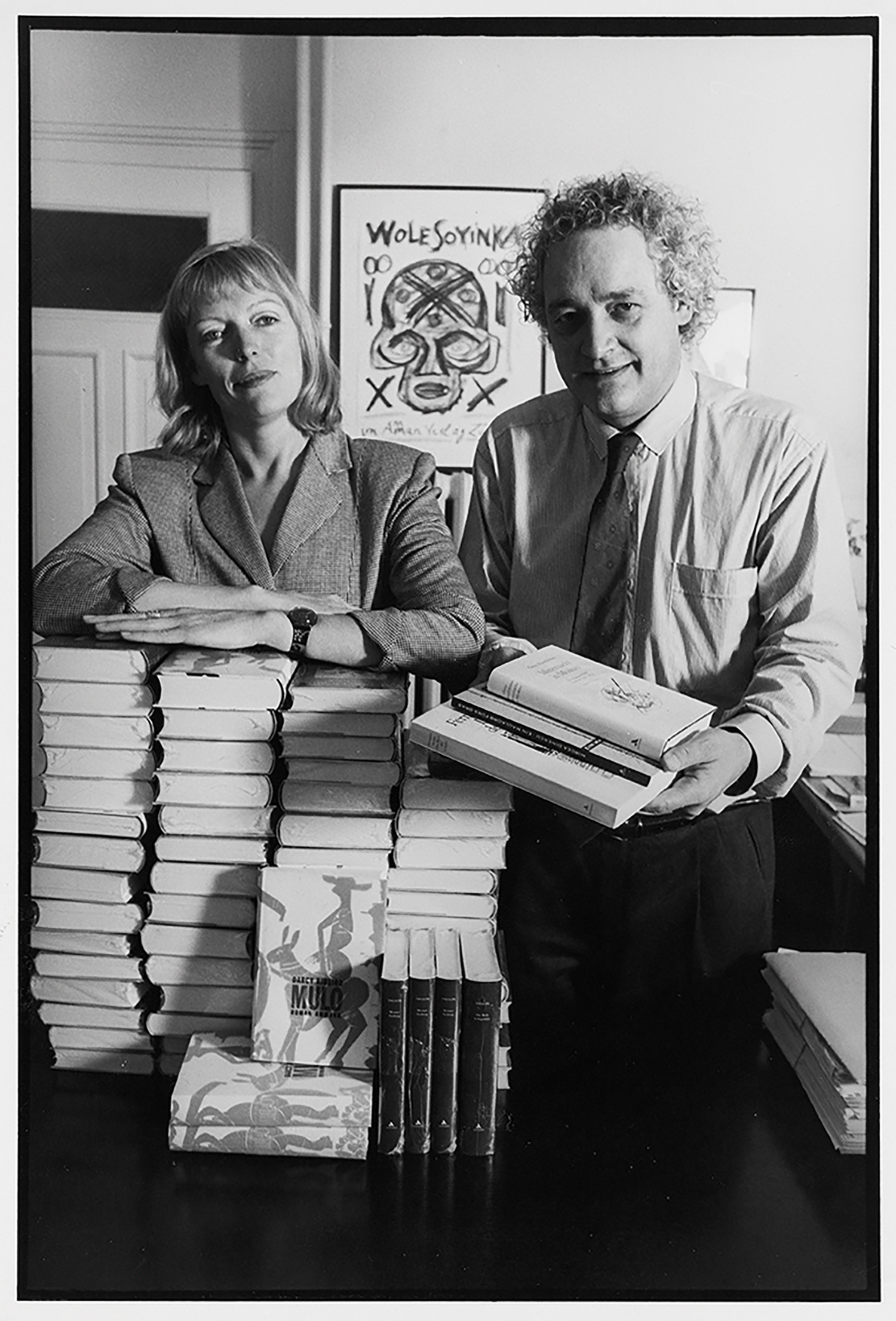

Ammann Verlag

Egon Amman’s first publishing project failed due to financial difficulties, but helped him to get an editorial job at Suhrkamp’s Zurich office. In 1981, he once again tried to get his publishing dream off the ground and founded Ammann Verlag with his wife Marie-Luise Flammersfeld. The publishing house’s first book was also the first book by the author Thomas Hürlimann – and Die Tessinerin (The Woman from Ticino) was a success.

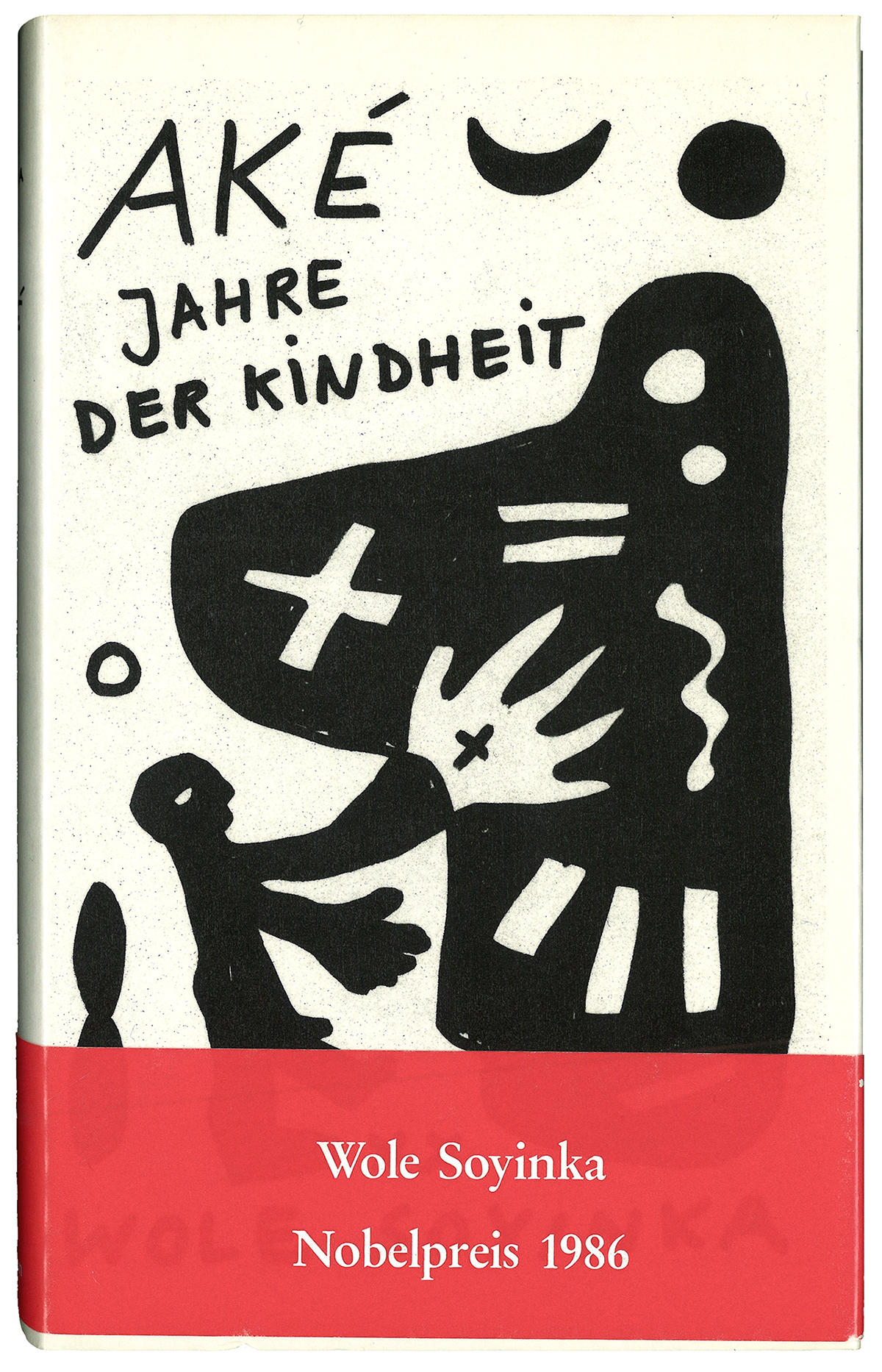

Over the course of almost 30 years, Amman Verlag published contemporary literature and major classics, such as Wole Soyinka’s Aké, which became a surprise bestseller thanks to the author’s Nobel Prize, and Dostoyevsky’s Elephants in the new translation by Swetlana Geier. In 2010, the publishers pulled the plug on their enterprise. ‘Not defeated, but tired of winning,’ said Egon Amman at the time.

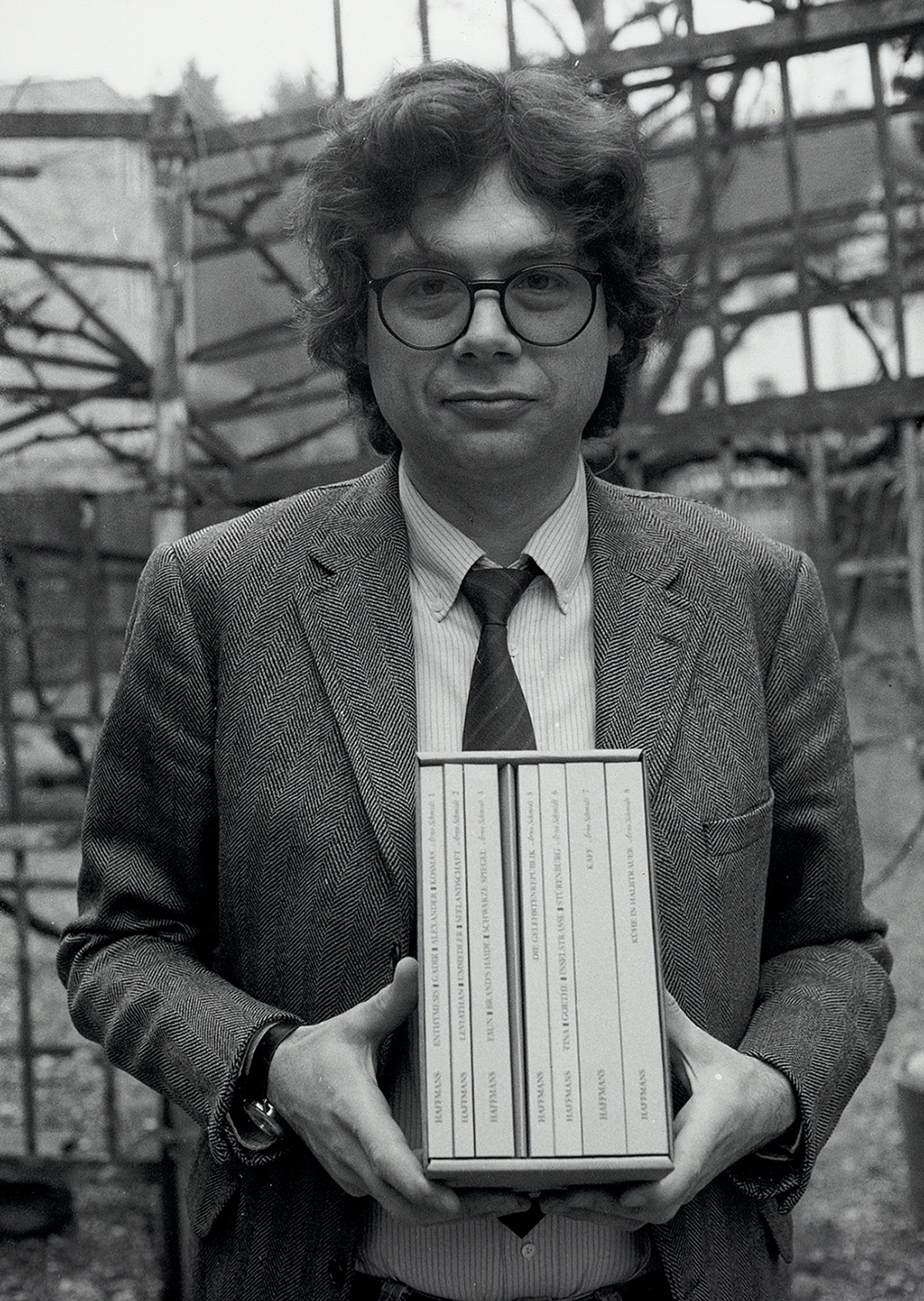

Haffmans Verlag

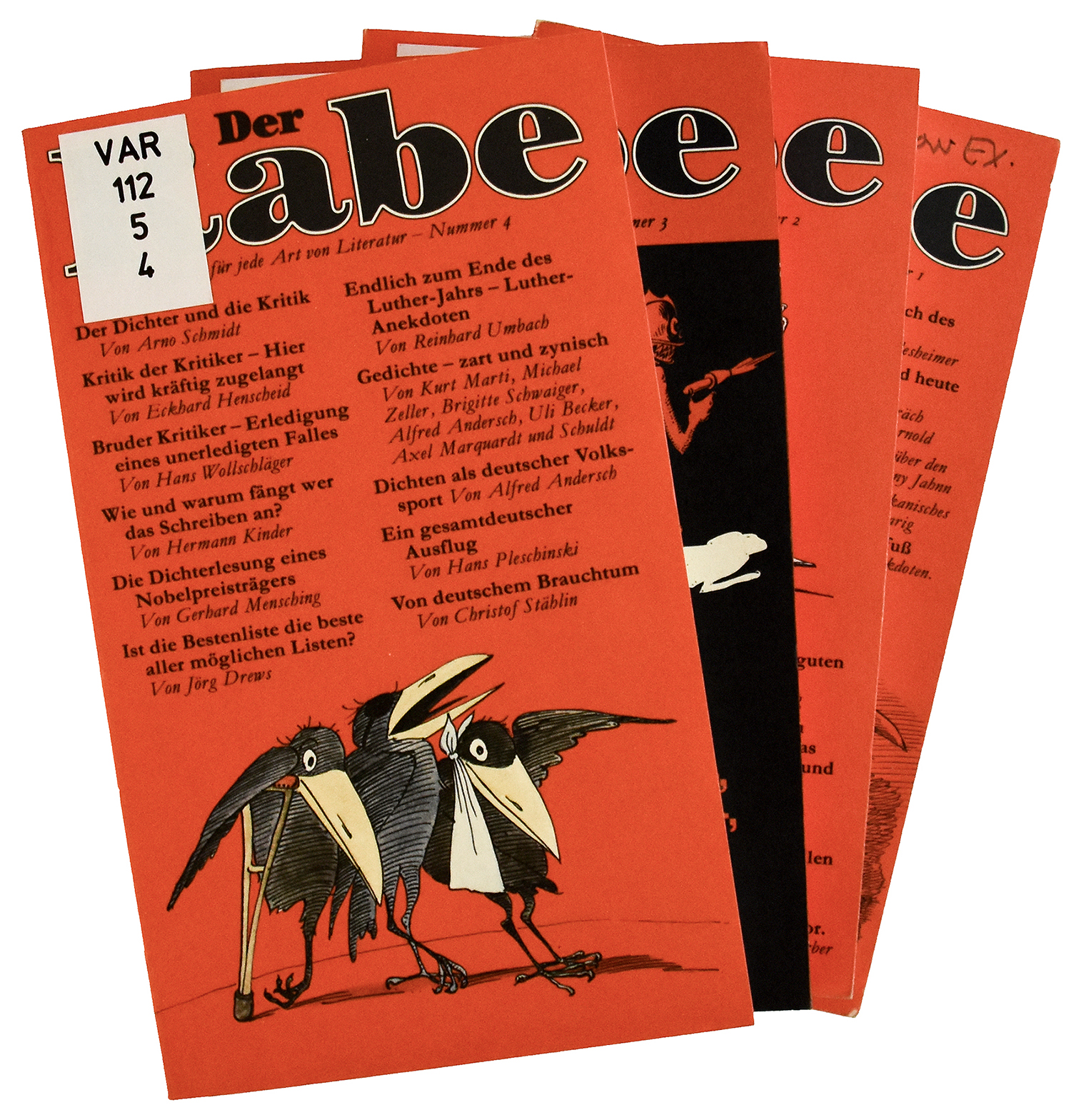

Gerd Haffmans worked for Diogenes Verlag before founding Haffmans Verlag in 1982 with Urs Jakob and Thomas Bodmer. Haffmans published comic literature as well as works by Arno Schmidt, who dared to mix the high-brow with the low-brow. The publishing house helped these genres gain recognition and played a role in them both making it onto newspapers’ features pages. New editions and new translations of classics were soon added to its programme.

After almost twenty years, Haffmans Verlag went bankrupt in 2001. Even the publisher’s mascot, a raven, was liquidated. Back then, ‘not only an unusual publishing house went bankrupt, but also an idea of literature,’ says the Süddeutsche Zeitung. As a brand within the publishing house and mail order company Zweitausendeins, publishers Gerd and Tini Haffmans continue to write their publishing history to this day.

edition sec52

Ricco Bilger opened his bookshop sec52 on Josefstrasse in 1983, adding edition sec52 in the same year. This rather unseasoned bookseller and publisher was in his mid-twenties and ‘half a punk’, as he once told Schweizer Buchhandel. He sold and published avant-garde works, underground pieces and new voices of Swiss literature. A gallery was attached to the bookshop.

In the 1990s, edition sec52 was transformed into the publishing house Ricco Bilger, which became bilgerverlag in 2001. Its publishing programme mainly includes Swiss and international literature, but occasionally also comprises different formats, such as books of photographs.

Nagel & Kimche

The publishing house Nagel & Kimche, founded in 1983, shaped the literary scene in Zurich for many years. From the off, Renate Nagel and Judith Kimche focused on contemporary Swiss literature and international children’s and young people’s literature. Biographies and non-fiction books were added over the course of time, as was the Nagel & Kimche series. The publishing house was sold to the Hanser Literaturverlage group in 1999, and it has been part of the Harper & Collins publishing group since 2023.

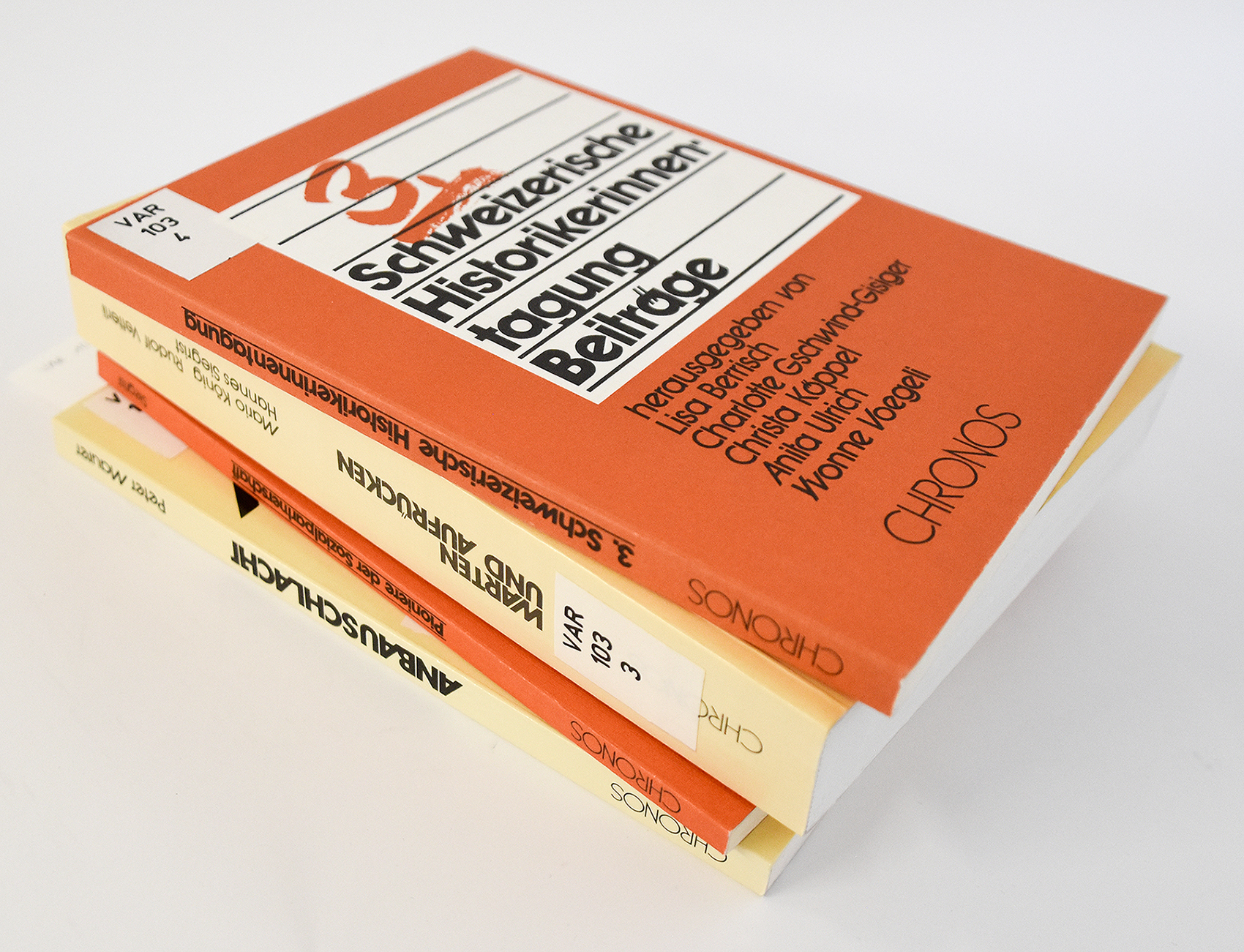

Chronos Verlag

Historians Dieter Brupbacher and Hans-Rudolf Wiedmer founded a publishing house in the critical left-wing space for books in their field, mainly from universities and the field of economic and social history, in 1985. The publishers never wanted to be political: their aim was to publish specialist works and, later, non-fiction books too. Nevertheless, Chronos Verlag was initially considered to be left-leaning.

The publishing company’s profile changed in the 1990s, hoping to address a broad audience without neglecting its academic underpinnings. Cultural history and current political issues complement its original focus to this day. In addition to works such as the 25-volume Bergier report, its programme includes, for instance, Susanna Schwager’s Fleisch und Blut (Flesh and Blood).

The indomitable publishers

Some fell by the wayside, while others were swallowed up by larger media houses. These bite-size histories of Zurich’s publishers reveal a trend that began in parallel with the wave of new publishing houses: a publishing crisis kicked off in the 1980s, and would only get worse the 1990s. There are various reasons for the ongoing process of concentration.

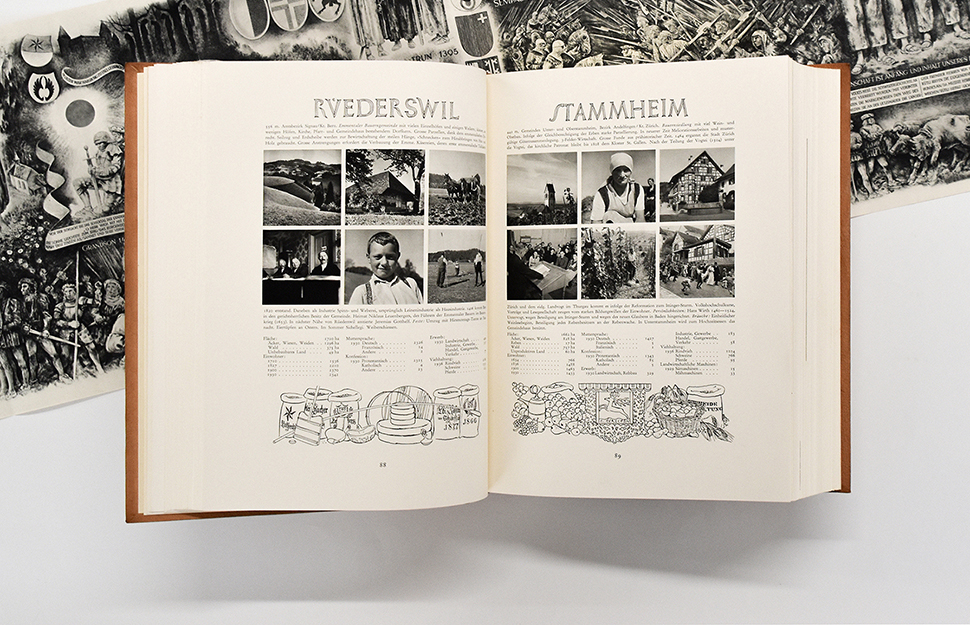

This pattern continued – and continues – in the new millennium. True, e-books have not been able to supplant printed books, but the change in the media brings with it all kinds of competition, and newspapers’ feature sections, which used to boost sales, have diminished greatly in importance. Publishing has remained a difficult business. The federal government has been offering a helping hand since 2016, but funding for publishing is a drop in the ocean. However, a few indomitable individuals have founded publishing houses in the 21st century. This is not due to their ignorance of the industry: Anne Rüffer, Yvonne-Denise Köchli, Sabine Dörlemann, Daniel Kampa and other Zurich-based publishers knew what they were getting into. A duo of publishers sum up why the adventure of publishing is worthwhile despite the challenging conditions:

‘Making books is still one of the best jobs in the world.’

Bruno Meier and Denise Schmid from Verlag Hier + Jetzt in ‘25x die Schweiz’ [‘25x Switzerland’].

Read more

- ‘Reformation als Auftrag: der Zürcher Drucker Christoph Froschauer the Elder’ (‘Reformation as an Order: the Zurich-based Printer Christoph Froschauer the Elder’) by Urs B. Leu in Buchdruck und Reformation in der Schweiz (Book-Printing and Reformation in Switzerland)

- Das Schweizerbuch im Zeitalter von Nationalsozialismus und Geistiger Landesdefense (Swiss Books in the Era of National Socialism and Intellectual National Defence) by Martin Dahinden

- Sternstunden or verpasste Chancen: zur Geschichte des Schweizer Buchhandels 1943–1952 (Golden Ages or Missed Opportunities: the History of the Swiss Book Trade 1943–1952) by Jürg Zbinden

- ‘Deutschschweizer Verlagslandschaft seit 1945’ (‘The Swiss-German publishing landscape since 1945’) by Rainer Diederichs in the volume Literatur – Verlag – Archiv (‘Literature – Publishers – Archive’)

- Publications on the individual publishing houses can be found via Swisscovery, for example on Ammann Verlag

- For anyone looking for updates from the horse’s mouth: Schweizer Buchhandel, the specialist magazine for the bookselling and publishing industry

- For researchers: our publishers’ book archives and publishers’ archives. The Global Archives project by the German Literature Archive Marbach enables our publishers’ book archives and publishing archives to be part of an international network.

Anita Gresele, Head of the Turicensia Department

Stefanie Ehrler, member of the Turicensia department

März 2024

Header-Bild: All in a row: an image from our publisher’s book archives. (ZB Zürich)

Pictures with © ProLitteris: all copyrights remain reserved. All reproductions and any other use without the permission of ProLitteris – with the exception of individual and private access to the works – are prohibited.

The latest issue of ZürichFenster showcases selected Zurich publishers and their publishing houses.

Special thanks

Many people have made this article possible, be it by providing information or approving the publication of images: the authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to them. Special thanks go to the publishers Tini Haffmans, Yvonne-Denise Köchli, Bruno Meier, Anne Rüffer and Denise Schmid as well as Urs B. Leu, Head of the Rare Books Department at Zentralbibliothek Zürich.