Money makes the world go round – a century of success for cooperative housing in Zurich

A century ago, Zurich’s Grand Council made a political decision that has had a lasting impact on the city ever since: it issued new regulations for the construction of non-profit housing, aiming to provide greater support for construction projects of this nature. In turn, this enabled Zurich’s construction cooperatives to flourish.

Zurich’s ‘Principles’

The new regulation came into force in 1924 in the form of the ‘Grundsätze betreffend die Unterstützung des gemeinnützigen Wohnungsbaues’ (‘Principles concerning the Support of Non-profit Housing Construction’). In Zurich, this funding comes from various sources, including credit facilities decided on by voters. These are supplemented by residual loans, the maximum amount of which was raised to 94% in 1924. At the same time, the city decided to participate financially in the cooperatives’ capital; this involvement was capped at 10%.

The ‘Principles’ only underwent minor amendments over the decades that followed and remained valid until 2012. The version in force since then is largely identical to the old one, but allows the city to instigate a change of use after expiry of the construction right if the plot is to serve a different purpose in the public interest.

The impetus for promoting non-profit housing came from times of acute housing shortages. Since then, the funding has proved its worth in the long run and is still of great importance today, as the city and surrounding area attract new residents.

Funding has an impact

Zurich’s support of non-profit housing construction offsets the social hardship fostered by the commercial real estate market. Why? Because non-profit housing construction is all about charging ‘cost rent’. This covers the cost of construction and maintenance; landlords forego any profit.

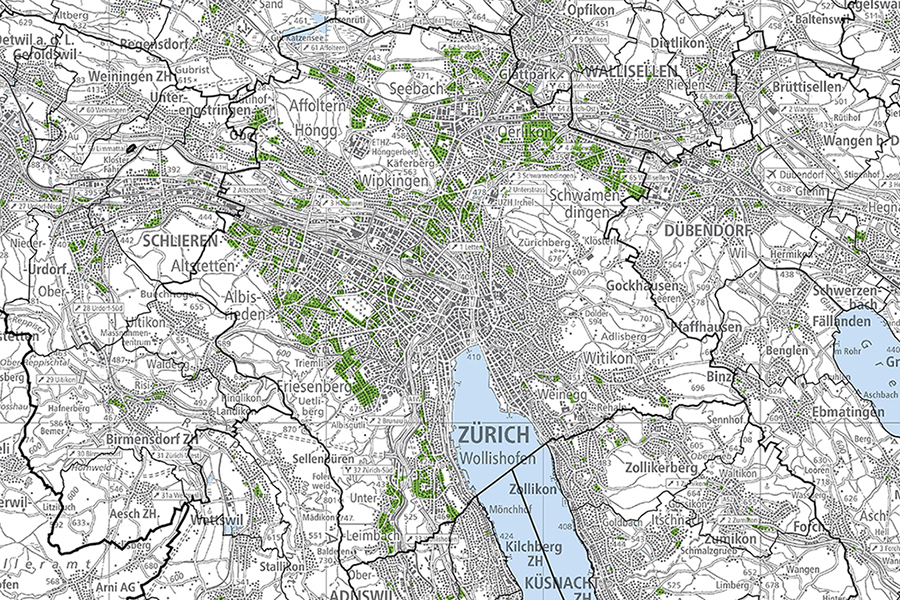

The enormous impact of Zurich’s ‘Principles’ is reflected in impressive figures: around a quarter of all residential units in the city of Zurich are non-profit. The support for the cooperatives has contributed the most to this impressive number, as their stock covers around three-quarters of this non-profit housing – 18% of all residential units in the city of Zurich. The remaining non-profit housing is owned by the city and its foundations. Non-profit housing developers only make up 5% of the market across Switzerland, but this number is 10% for the canton of Zurich.

In 2022, there were 41,352 cooperatively owned apartments in the city of Zurich – so many that they give some of Zurich’s neighbourhoods a unique appearance. This large number underscores the success of the funding provided.

Everyone benefits

The figures show that supporting non-profit housing construction in the city of Zurich benefits large swathes of the population. The aim was to combine smart housing policies with effective social policies – and this aim was achieved.

In addition, the authorities shape the city via their housing funding. When a cooperative receives funding, the city takes a seat on its board and can thus influence the development of the community in question. The funding conditions also include architectural competitions, often resulting in responsible and well-designed residential buildings. It is no coincidence that some cooperative buildings are now considered valuable parts of the city’s historical heritage.

Besides providing money, Zurich has made its own land (some of which was newly acquired for this purpose) available for non-profit housing projects on a large scale. Along with non-profit residential buildings, these plots also house other amenities required by a functioning and liveable city – transport infrastructure, schools, green spaces and much more – which often benefit the entire population.

Looking back: six key periods

The city of Zurich supported non-profit and cooperative housing – albeit to a lesser extent – even before the ‘Principles’ of 1924. Given the economic situation, this support was urgently needed. Cooperative residential buildings underwent architectural changes over the decades that followed: they too are testament to their respective times.

The shortage of workers’ housing

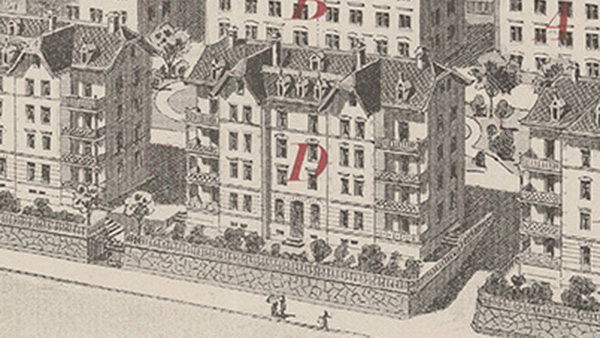

When development began, the city was facing a housing shortage due to industrialisation. Immigrant workers had no idea where to stay, and families had to live in confined spaces, sometimes even sharing them with other tenants. Aussersihl, which was not yet part of the city of Zurich at the time, was particularly badly affected.

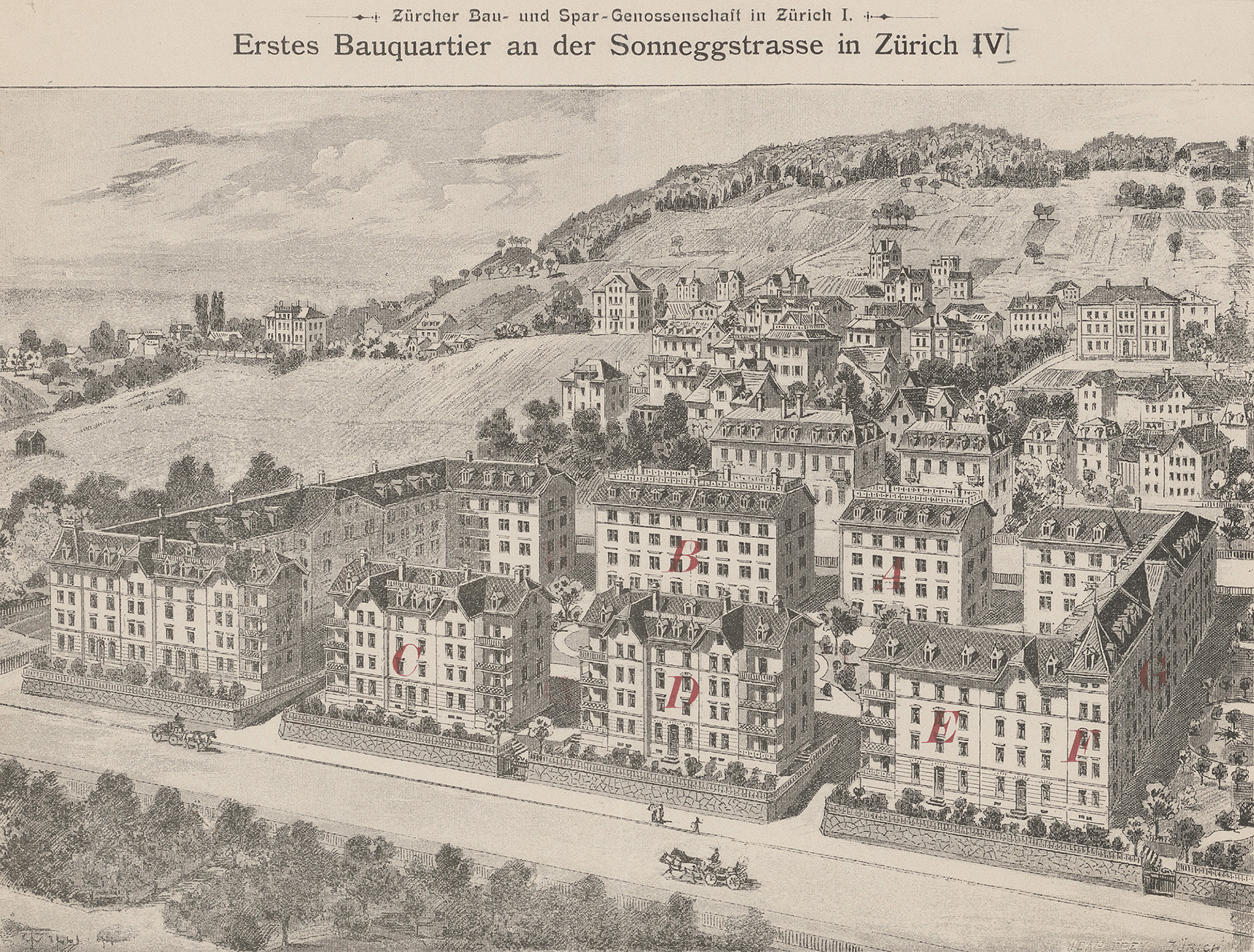

Tenants in Zurich joined forces to form an association as early as 1891. Two years later, this became the ‘Zürcher Bau- und Spargenossenschaft’ (‘Zurich Construction and Savings Cooperative’, ZBWG). Urban planners developed architectural social utopias, such as the garden city, in response to the miserable situation. While these were popular in Zurich, traditional forms such as detached houses and buildings in the local style also came to the fore of cooperative construction here.

Municipal funding begins

A broad political alliance with the Social Democrats – now a stronger force – kick-started housing funding in the early 20th century. The city council had commissioned a study back in 1896, which showed that there was not enough cheap accommodation available. This led to funding being made available: from 1907 onwards, this was via a referendum to build non-profit municipal housing and from 1910 onwards, through the provision of support to cooperatives.

The first housing cooperative funded by the city was the ‘Genossenschaft zur Beschaffung billiger Wohnungen’ (‘Cooperative for Creating Cheaper Housing’; today Berowisa), which has its ‘residential colony’ on the site between Bertastrasse and Wiesendangerstrasse. This and similar projects represented a ray of hope. However, because funds were very limited, the success of municipal funding remained modest at first.

An upsurge from 1924

A significant upswing in cooperative housing was possible from 1924 onwards thanks to increased municipal funding. The new non-profit residential buildings aligned with the city’s self-image as ‘Red Zurich’ in the following years, when the Socialist Party dominated the city government. The leading figure was Emil Klöti, who took over as mayor in 1928 and was the first president of the ‘Schweizerischen Verbandes für Wohnungswesen’ (‘Swiss Housing Association’). He pushed ahead with non-profit housing construction in Zurich.

The new funding policy went hand in hand with a shift towards modern design, as is evident in the guiding principles for building subsistence dwellings. In Zurich, this is demonstrated by prototype buildings such as the ‘Rotach’ show houses (1928) by Max Ernst Haefeli and the Neubühl Werkbund housing estate (1930–1932). Modernist trends are also reflected in the concept of adapting buildings to align with forms of industrialisation and rationalisation. This goes well with the image of a major city in the interwar period, an image that Zurich was starting to align with.

The desire to create homes with plenty of fresh air and sunshine also changed the architectural landscape permanently. Instead of densely-packed buildings, there were now empty plots of land with more open-ended uses. One example of this is the 1931 Sonnenhalde I housing development belonging to the Freiblick building cooperative, which is to be demolished soon.

The war and post-war period

The state supported non-profit housing throughout Switzerland during the Second World War. Cooperative buildings constructed between the 1940s and 1960s continue to shape many streets in Zurich today. This can be seen in various areas, including in Karl Kündig’s Heiligfeld estate belonging to the St. Jakob building cooperative (1943–46), which stretches along Brahmsstrasse and Albisriederstrasse. However, this rise led to saturation and monotony in the mass housing space. This was also exacerbated by the private-sector construction industry, which followed similar approaches throughout Switzerland.

These identikit estates were one of the objects of criticism in the pamphlet ‘achtung: die Schweiz’ (‘caution: Switzerland’) from 1955, written by the authors associated with Max Frisch. Nevertheless, even during this time, there were cooperative buildings that broke the usual mould. Ernst Giesel’s studio and apartment building on Wuhrstrasse is a clear example of this.

Turbulent times: 1968 and its consequences

The emergence of social criticism from the late 1960s onwards also had an impact on the urban environment. The 68 movement protested against the demolition and expensive renovation of properties.

Some of the property owners at the time founded alternative cooperatives, such as Wogeno. The idea of creatively repurposing existing buildings and developing independent organisational structures for this purpose is also reflected in the Dreieck (‘Triangle’) cooperative. This organisation was formed in the 1980s and emerged from resistance to the demolition of houses by the city. It was successful: instead of connecting Zurich more closely to the motorway, a historic section of Werd was preserved and gaps between buildings closed in a sensible way. This approach of constructing buildings within existing space is more topical than ever.

Developments in the 21st century

Urban densification, in particular, has become more important since the turn of the 21st century – and cooperatives have contributed to this. In Zurich, high-density construction can be seen in projects on high-yield plots along the railway line, such as the Zollhaus development by the ‘Kalkbreite’ cooperative. Discussions about the future of housing also led to the founding of ‘mehr als wohnen’ (‘more than housing’) in 2007 – a merger of several cooperatives – which sets store by participation. This organisation took over the successful development of the Hunziker site in Leutschenbach, which 1,200 people now call home.

The situation in the anniversary year

A hundred years after the ‘Principles’ were issued, the question is what the future will look like. The previous trend is continuing – as demonstrated by the fact that cooperatives are heavily involved in current projects, such as the Koch site under construction at present. However, housing cooperatives need to adapt to a new world: the population has changed, and so have expectations of our residences, say, in terms of eco-friendliness and sustainability.

While households are getting smaller, the amount of space required by each individual has increased. This can be counteracted in various ways, such as by experimenting with more diverse floor plans. Creating facilities that are shared among all tenants also gives rise to innovative solutions, and strengthens cultural integration and social cohesion to boot. As a result, attractive cooperative buildings now function as a flagship form of architecture that attracts new residents to the city and makes them feel at home here.

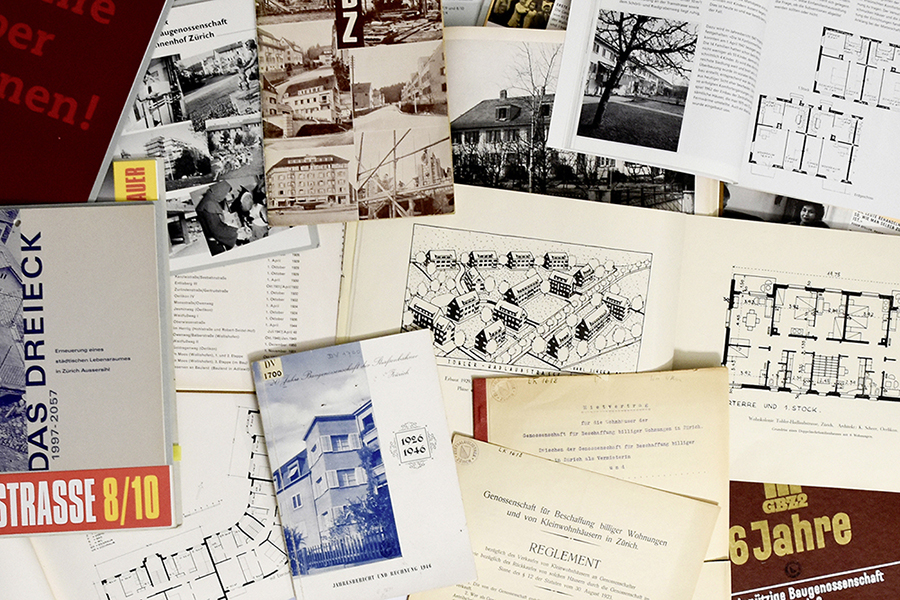

Cooperative construction in Zurich: read more

- ‘Kommunaler und genossenschaftlicher Wohnungsbau in Zürich. Ein Inventar der durch die Stadt geförderten Wohnbauten 1907–1989’ (‘Municipal and Cooperative Housing Construction in Zurich: An Inventory of the Residential Buildings Funded by the City 1907–1989’) published by the City of Zurich, Finance Office and Construction Office II

- ‘Wegweisend wohnen.Gemeinnütziger Wohnungsbau im Kanton Zürich an der Schwelle zum 21. Jahrhundert’ (‘Housing Pioneers. Non-profit Housing Construction in the Canton of Zurich on the Threshold of the 21st Century’) edited by Christian Caduff and Jean-Pierre Kuster

- ‘Mehr als Wohnen. Gemeinnütziger Wohnungsbau in Zürich 1907–2007. Bauten und Siedlungen’ (‘More than Housing. Non-profit Residential Dwellings in Zurich 1907–2007. Buildings and Estates.’) published by the city of Zurich, Office for Building Construction

- ‘Wohnen morgen. Standortbestimmung und Perspektiven des gemeinnützigen Wohnungsbau’ (‘Living in the Future. Stocktake and Outlook for Cooperative Housing Construction’) published by the City of Zurich and the Swiss Housing Association

- ‘Wohngenossenschaften in Zürich’:Gartenstädte und neue Nachbarschaften’ (‘Housing Cooperatives in Zurich: Garden Towns and New Neighbourhoods’) edited by Dominique Boudet

- Wohnen, the magazine of Wohnbaugenossenschaften Schweiz, the association of non-profit housing developers, online and in print

- Celebratory issues and other publications by Zurich housing cooperatives can be found at Swisscovery.

Dr. Lothar Schmitt, Liaison Librarian for Art, Architecture and Archaeology

January 2024

Header-Bild: Die Kolonie der Genossenschaft Eigen Heim am Zürichhorn in Zürich um die Jahrhundertwende, Ausschnitt. (ZB Zürich)