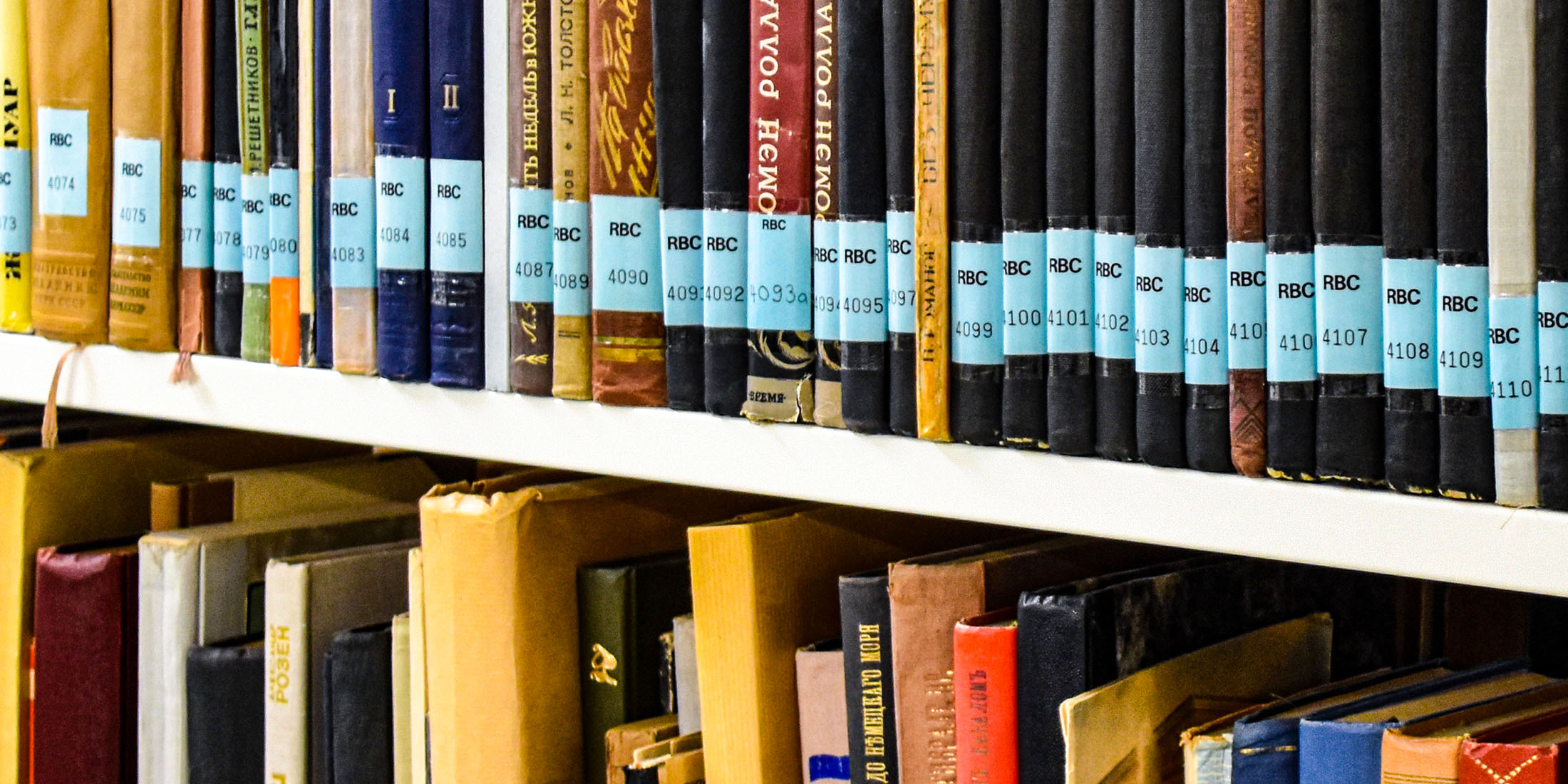

The Russian Library Zurich (RBC): History and Stories

From 1927 to 1983, there was an association in Zurich dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of Slavic literature. The Russian Library Zurich (Russische Bibliothek Zürich, RBC), which was run on a voluntary basis, offered its members – including citizens of various Slavic nations, Swiss-Russians and Soviet dissidents – a large selection of Russian-language titles. The unique collection of books and the association’s archive have belonged to the Zentralbibliothek Zürich since 2002.

‘It’s great that they are here!’

(Как приятно, что она здесь существует!)

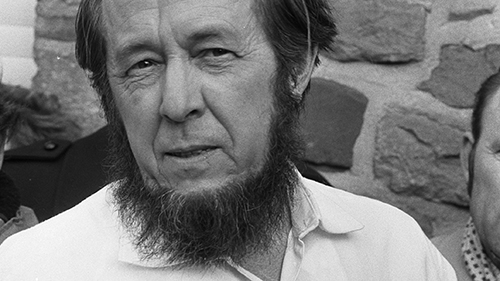

Aleksandr Solženicyn* on the RBC, Zurich, 16 April 1975. Copy of a dedication from the RBC archives. (ZB Zürich, Hs AR 10, M1)

* For this article, the Russian-Cyrillic alphabet has been transliterated according to DIN 1460-1.

The founding years

‘For more than forty years, there has been an institution in our city that not many people know about but which has been quietly carrying out valuable cultural work.’ This is how Ella Studer, a long-standing employee of the association, described the work of the Russian Library Zurich in the ‘Neue Zürcher Zeitung’ newspaper of 15 January 1970. In fact, the association, which managed to operate without any public funding, performed an important function within Slavic and Slavophile circles in Zurich – and far beyond.

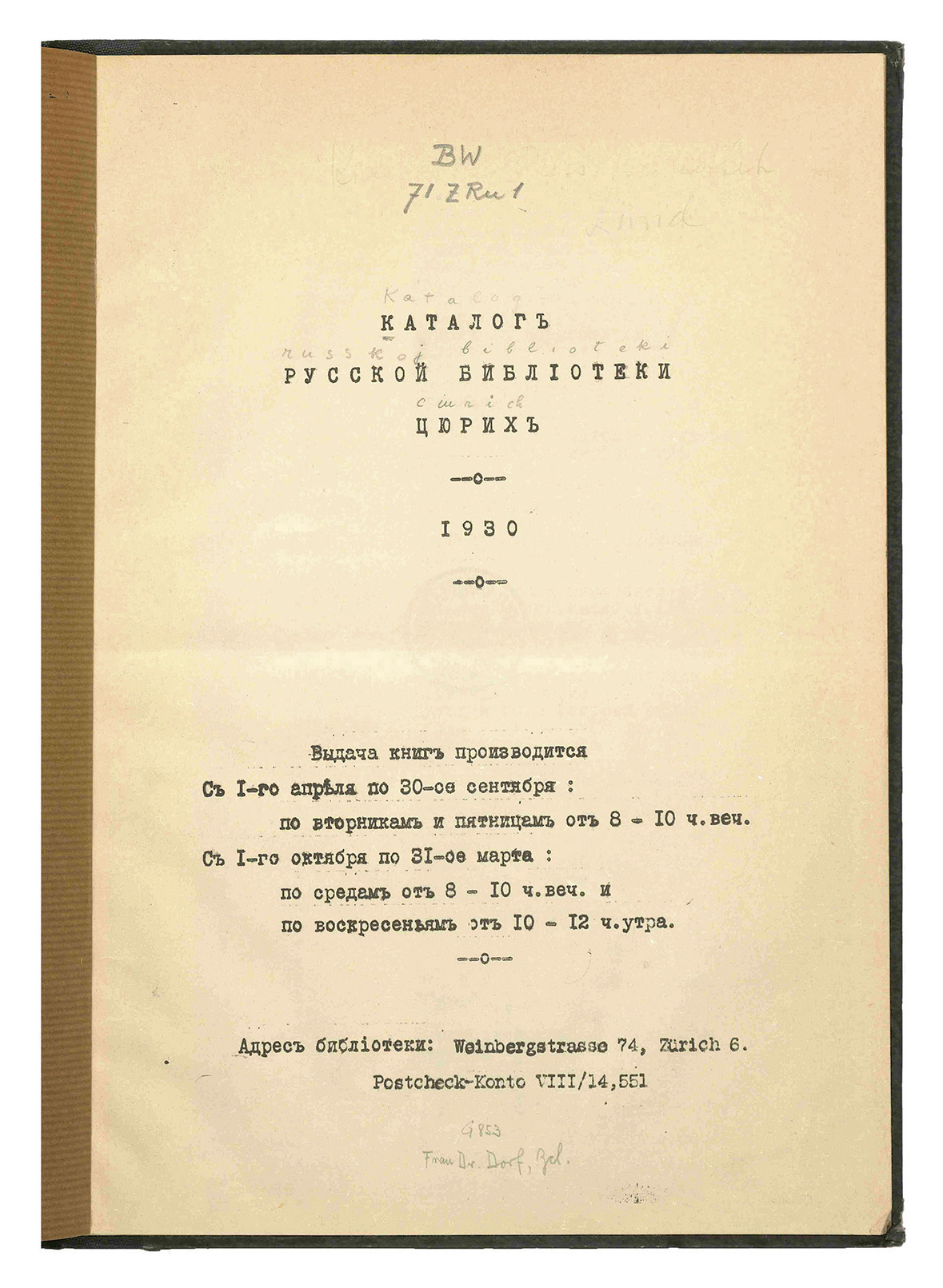

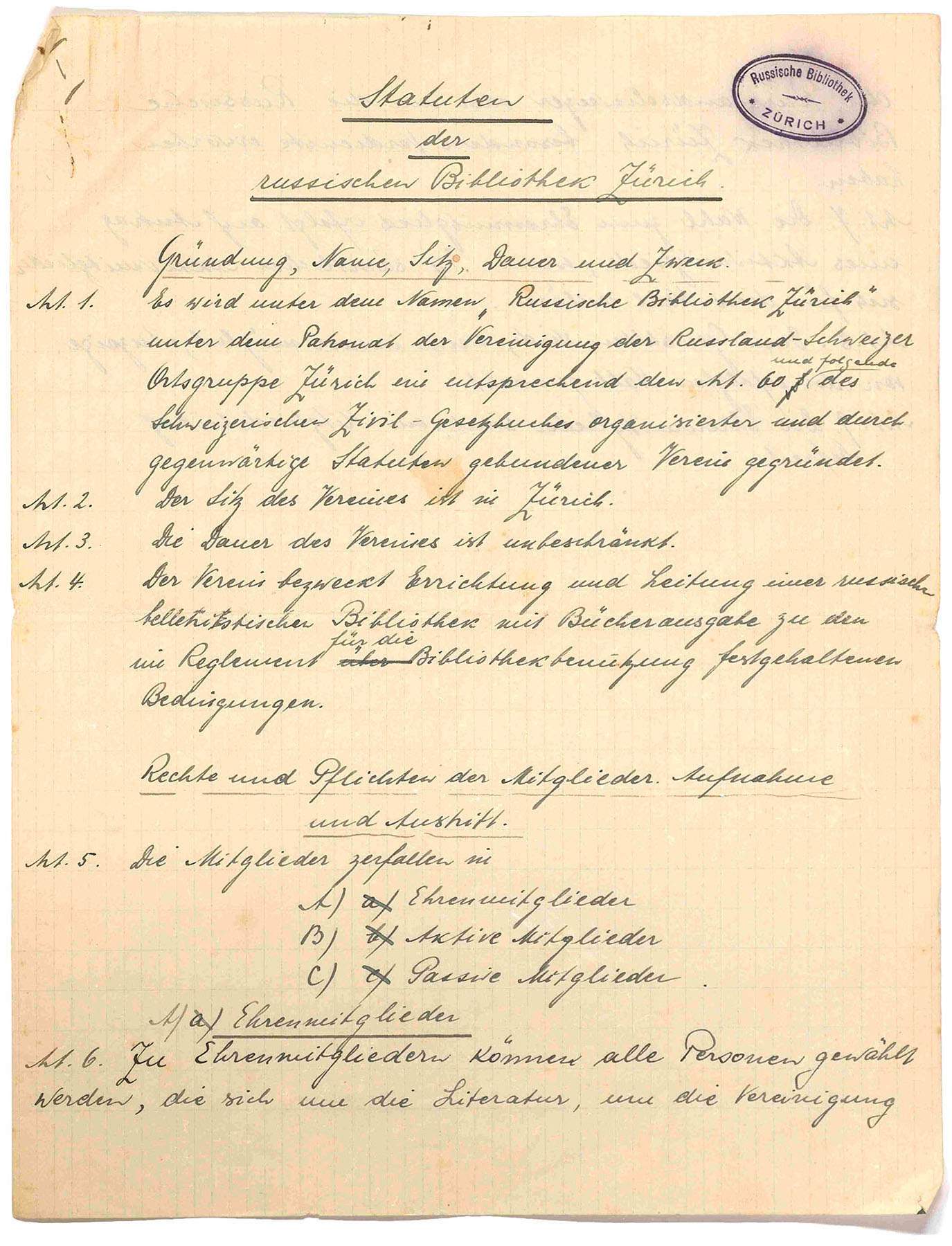

The idea of founding a Russian library in Zurich was suggested by the numerous Swiss-Russians who had returned to Switzerland, often involuntarily, after the October Revolution of 1917. The Russkaja Biblioteka v Cjuriche (RBC) opened its doors in 1927 with a collection of only around 400 books. The first premises was in the basement of a house at Weinbergstrasse 74 in Zurich.

The opening of the library was preceded by the founding of the association of the same name, which only had limited funds. Out of consideration for the financial situation of its members, the monthly subscription fee was initially only 1.50 francs. This revenue was used to pay for facility rental and for new acquisitions. At that time, Russian-language literature was not readily available in bookshops in Zurich. Nevertheless, the RBC managed to expand the collection of books to around 2,000 titles in just two years.

‘There were no Russian books in the bookshops of Zurich. Catalogues had to be sent from Berlin, Paris and Prague in order to select and order the books.’

‘The History of the Foundation of the “Russian Library”’, anonymous, 18 April 1975. Typescript from the RBC archive. (ZB Zürich, Hs AR 10, M5)

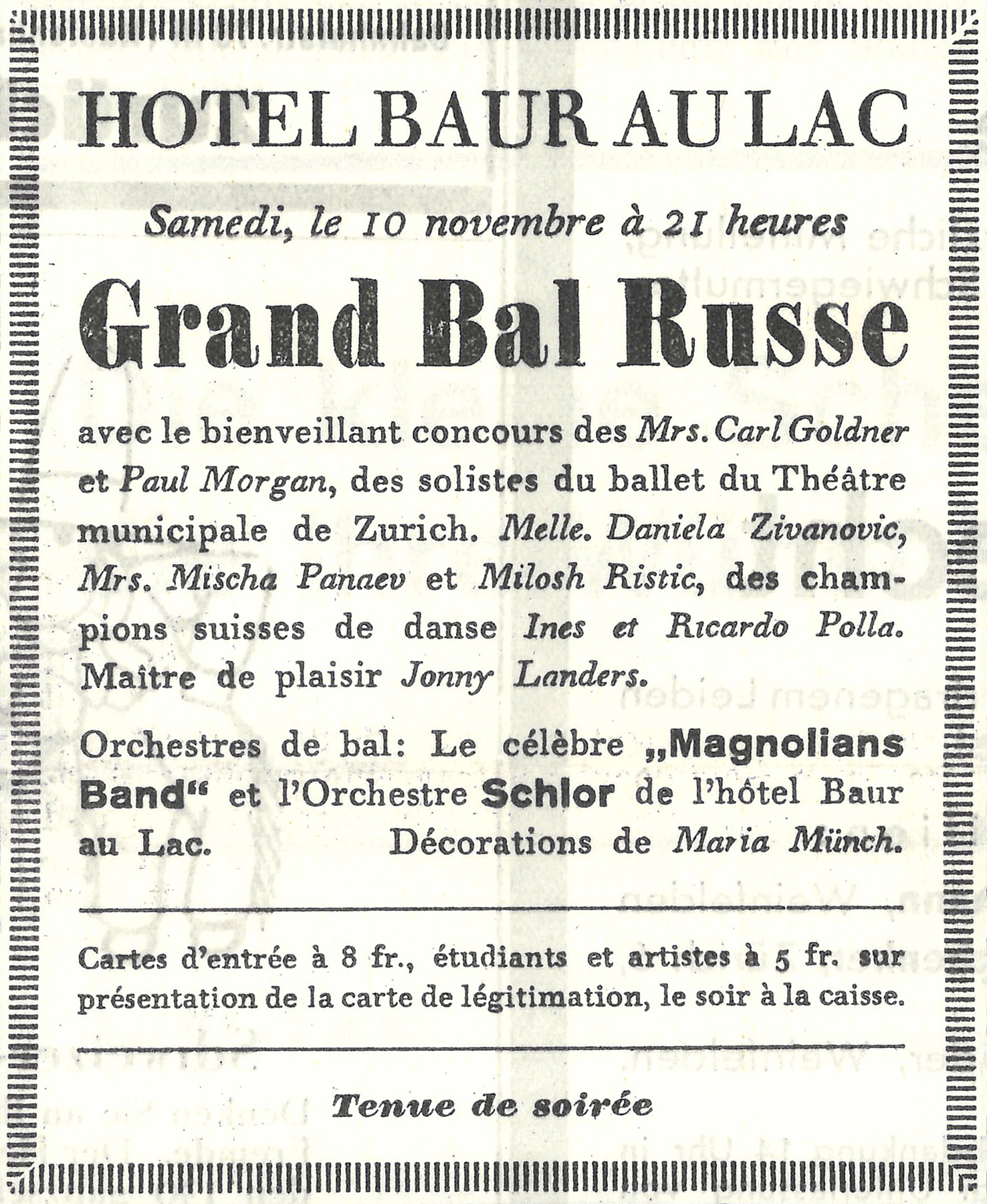

Grand Bal Russe

Little is known about what else the association did, beyond running the library. In the 1930s, however, it did host a charity ball in Zurich, the Grand Bal Russe.

‘Saturday, 10 November, at 9 pm, the Grand Bal Russe will take place in the Hotel Baur au Lac. Performing will be Carl Goldner and Paul Morgan, soloists of the Stadttheater Ballett [...], as well as the Swiss masters of ballroom dance [...]. In the [...] decorated rooms, guests can expect all sorts of surprises. The net proceeds will be donated to the relief fund of the Cercle Suisso-Russe and to the Russian library.’

Announcement in the ‘Neue Zürcher Zeitung’ newspaper, 7 November 1934.

The president of the Association of Russian Emigrants invited the Russian library association’s board of directors to host the annual ball at the Baur au Lac hotel or the Dolder Grand hotel. Despite some reservations – after all, the RBC had no experience in hosting such an exclusive event – the board accepted the offer.

The lavishly designed dance events, which included cabaret performances and tombolas, developed a very good reputation within Zurich high society. At the Grand Bal Russe of 1934, the famous Zurich photographer Jakob Tuggener photographed the illustrious goings-on of the guests at the ball with his Leica camera for the first time. He followed the event for years and immortalised it in his series entitled Ballnächte.

Worries and glimmers of hope

The profits from the Grand Bal Russe brought temporary financial relief, but after a few years, the RBC stopped organising the ball. In early 1938, in a letter to the association’s members, the board of directors openly admitted that the first ten years of library operation had been ‘tough’. They requested that the 5 francs members had paid as a deposit be converted into a donation.

The association also contacted the then Mayor of Zurich Emil Klöti and asked the city for a free or at least inexpensive property to use. The board feared that, without this help, there was a danger that ‘the library, which has a valuable collection of books that is probably unique in Switzerland, [...] will have to close down’. The RBC also asked the cantonal education department for support, but both requests were turned down.

In addition to all of the difficulties, there were positive developments, primarily in relation to the recognition of the library. The City of Zurich Directory listed the RBC in the ‘Libraries’ section from 1943, alongside the Swiss Social Archives, the Pestalozzi Society and the Zentralbibliothek. In 1977, it was also included in the ‘Libraries in Zurich’ guide. In the same year, the Swiss press celebrated the association’s 50th anniversary, and the library even received attention in the Soviet Union.

Library operation

At the end of the 1950s, the RBC moved into an apartment at Freiestrasse 101 in Hottingen, Zurich. The previous monthly fee of 1.50 francs was increased to 2 francs. The library now comprised more than 4,000 titles and was open one evening a week. Volunteer staff – most of them women – attended to the visitors.

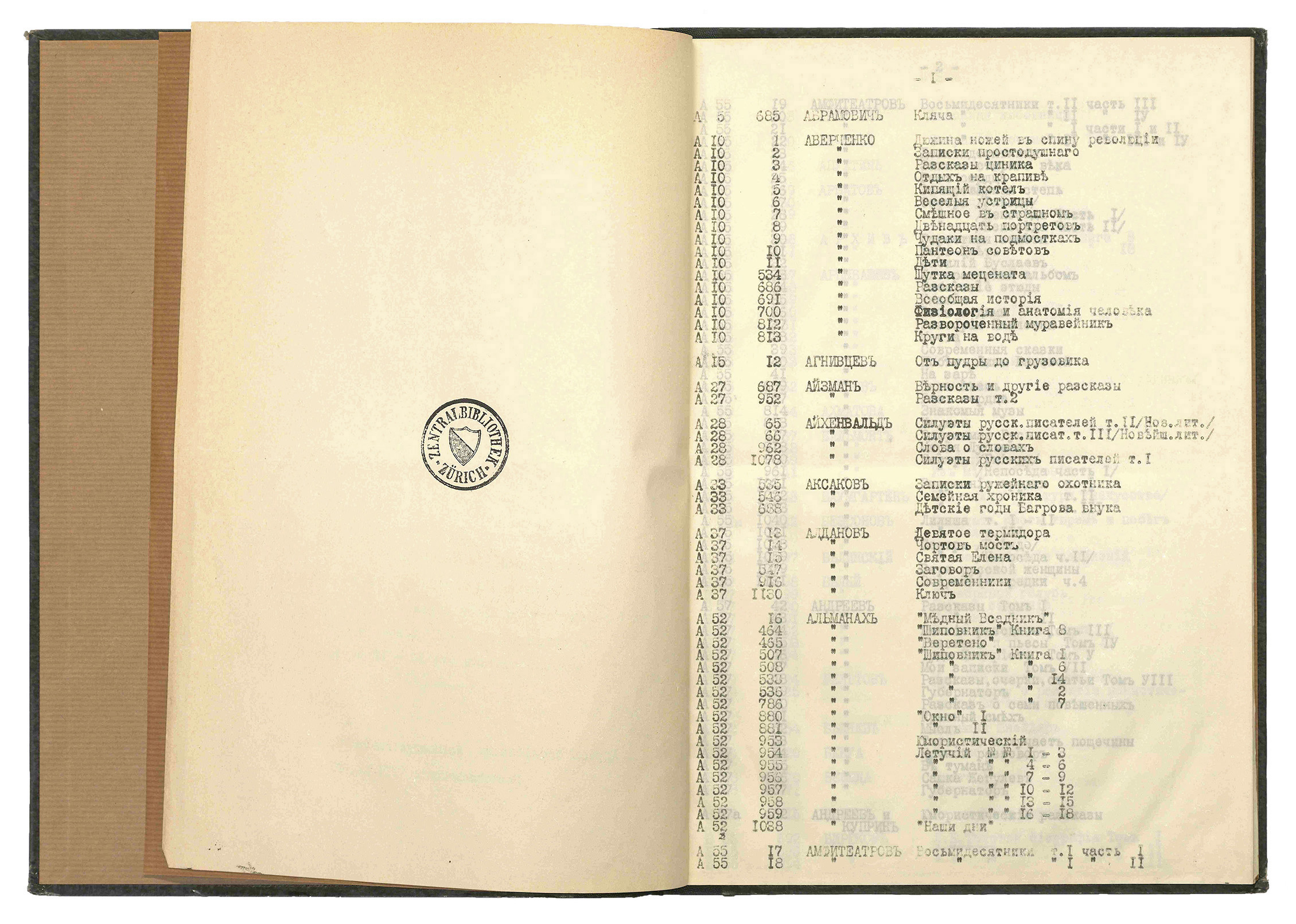

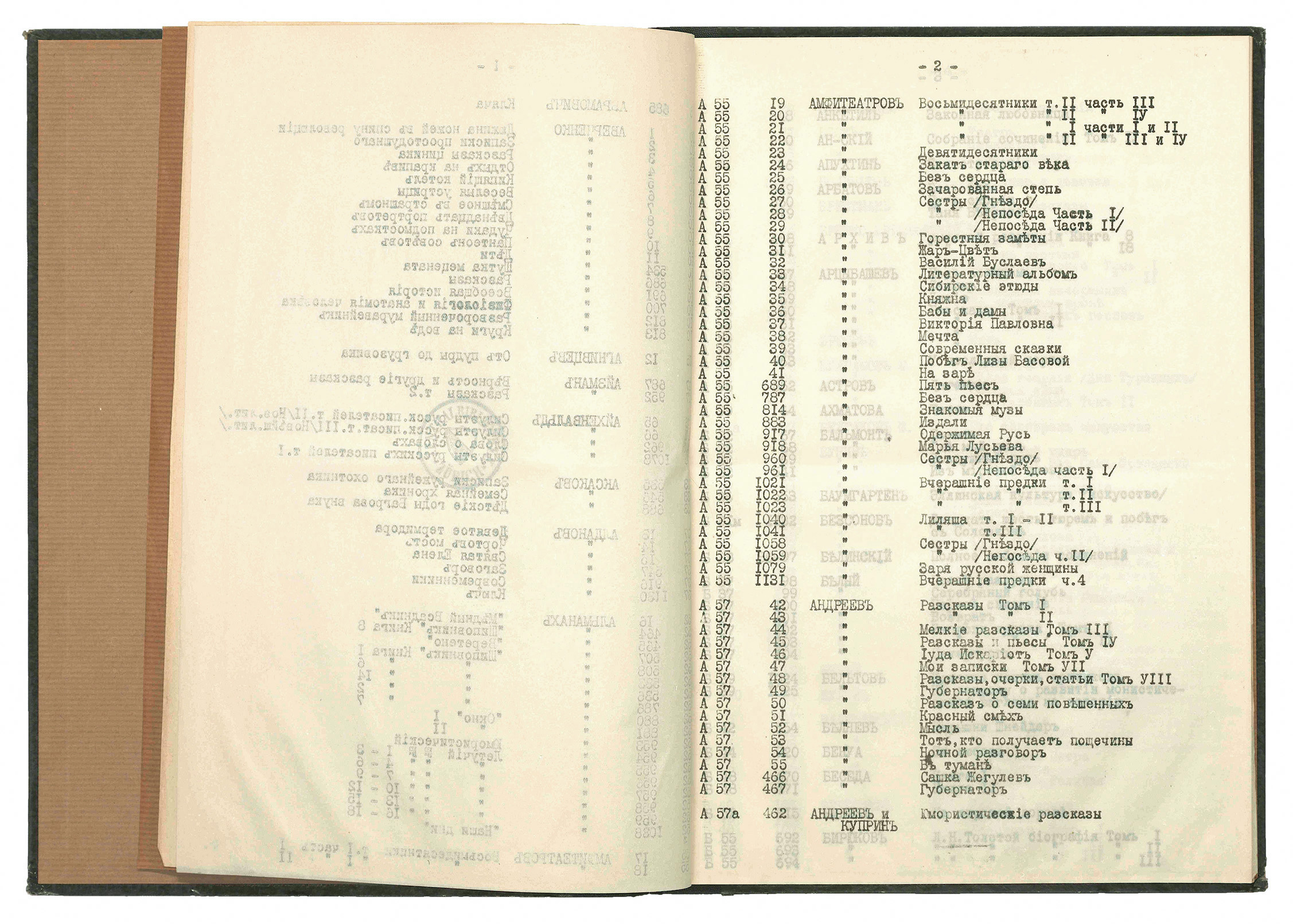

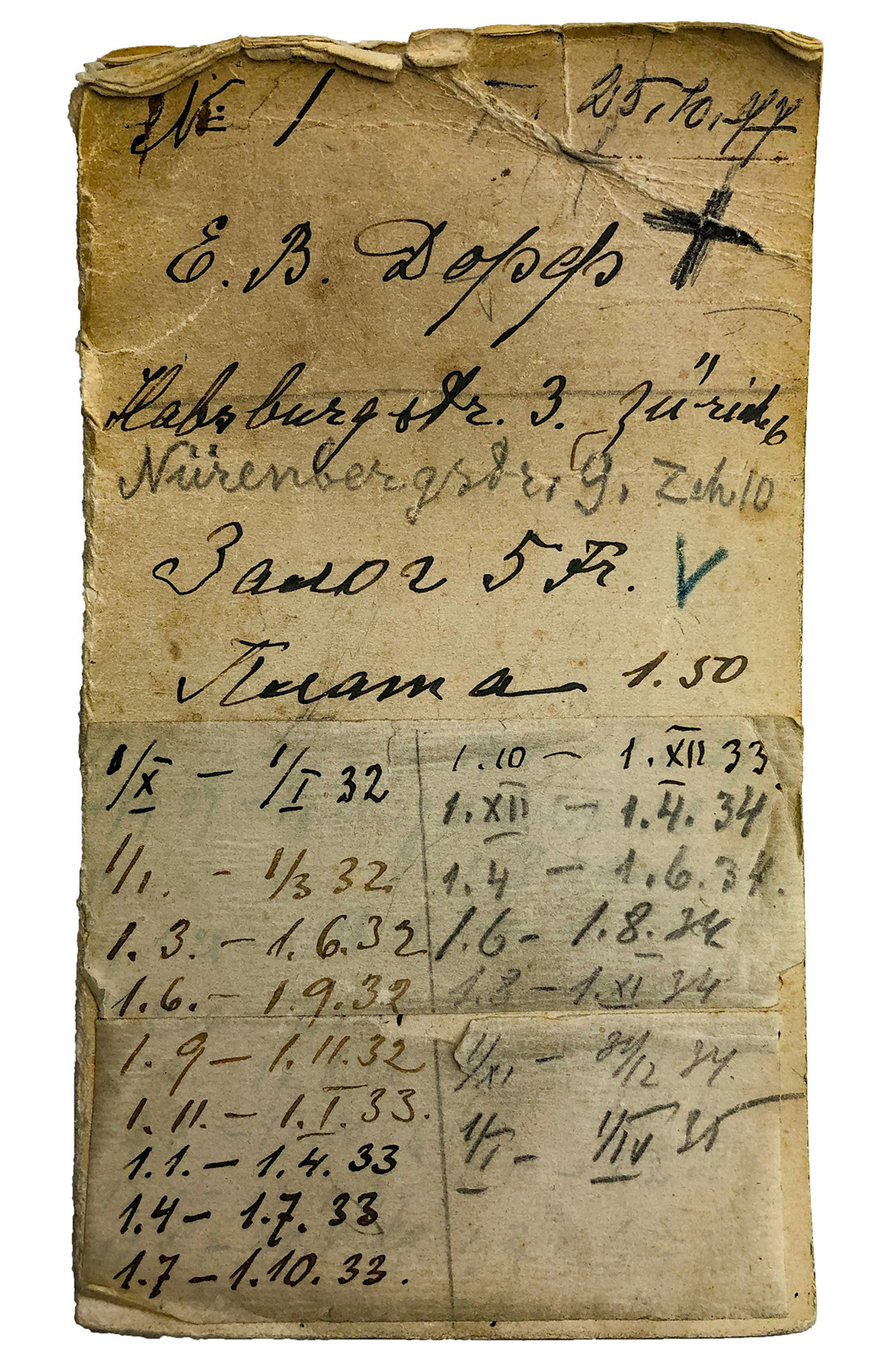

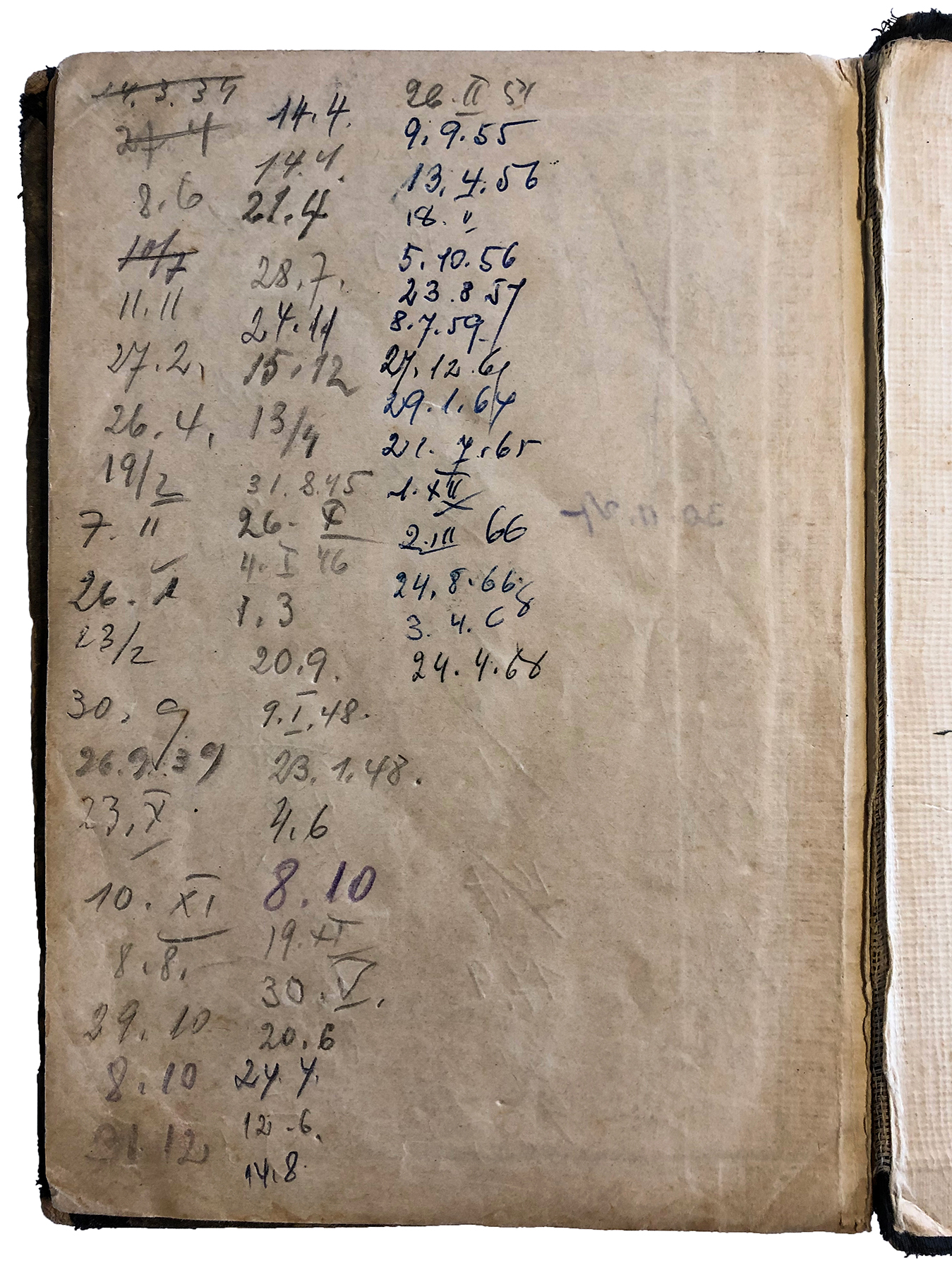

Library operations were simple but effective: members were given a sequentially numbered index card on which it was noted whether the monthly fee had been paid. Books could be borrowed for up to three weeks. The loan note was often simply placed on the endpapers in the books themselves. A regularly updated catalogue listing the titles in alphabetical order provided orientation.

‘Every Wednesday evening, from 7:30 p.m. to 9 pm, there is life in this narrow, book-filled space.’

This is how Ella Studer (1902–1992) described the busy evenings in the RBC. It was mainly thanks to her that the library collections were organised in such a practical way, since she was the only trained librarian among the volunteers. Studer, whose family originally came from Saint Petersburg, was the Pestalozzi Society’s first chief librarian for more than thirty years.

As an extra service, the RBC staff sent packages of books to members throughout Switzerland – an offer that many took advantage of. On average, 80 to 100 volumes were checked out each evening, and more than half of these were requested by telephone and sent by post. The book shipments were dispatched not only to private households but also to sanatoriums, psychiatric hospitals and even a prison and an internment camp.

Members

When it was first founded, the RBC received an interest-free loan of 3,000 francs from a private source, with the condition that 25 members would be recruited – a requirement that the association more than fulfilled in the first year. When it disbanded in 1983, its membership list contained 883 entries. That being said, the numbers of members who left or who died were often reassigned; moreover, it was not uncommon for several people, such as married couples, to be listed under one number.

The founding members of the association were Swiss-Russian. But membership soon began to include Russians who had emigrated to Switzerland and citizens of other Slavic nations, as well as Swiss nationals who spoke Russian or wanted to learn it. Most of the members came from Zurich, and some lived in Bern, Geneva, Lausanne, Locarno and Solothurn.

The association was politically independent and included members from different camps. Their positions ranged from pro-Soviet and democratic to anti-Bolshevik and monarchist. Among them were clergymen and professors, engineers and doctors, clerks and electricians, an opera singer and a ballet dancer. For many, attending the RBC was an opportunity to connect with a lost homeland.

Many of the members had eventful biographies shaped by the upheavals of the 20th century. Some left their mark on the history of the city of Zurich, and others also had an impact far beyond it. Five members of the RBC are presented below as examples.

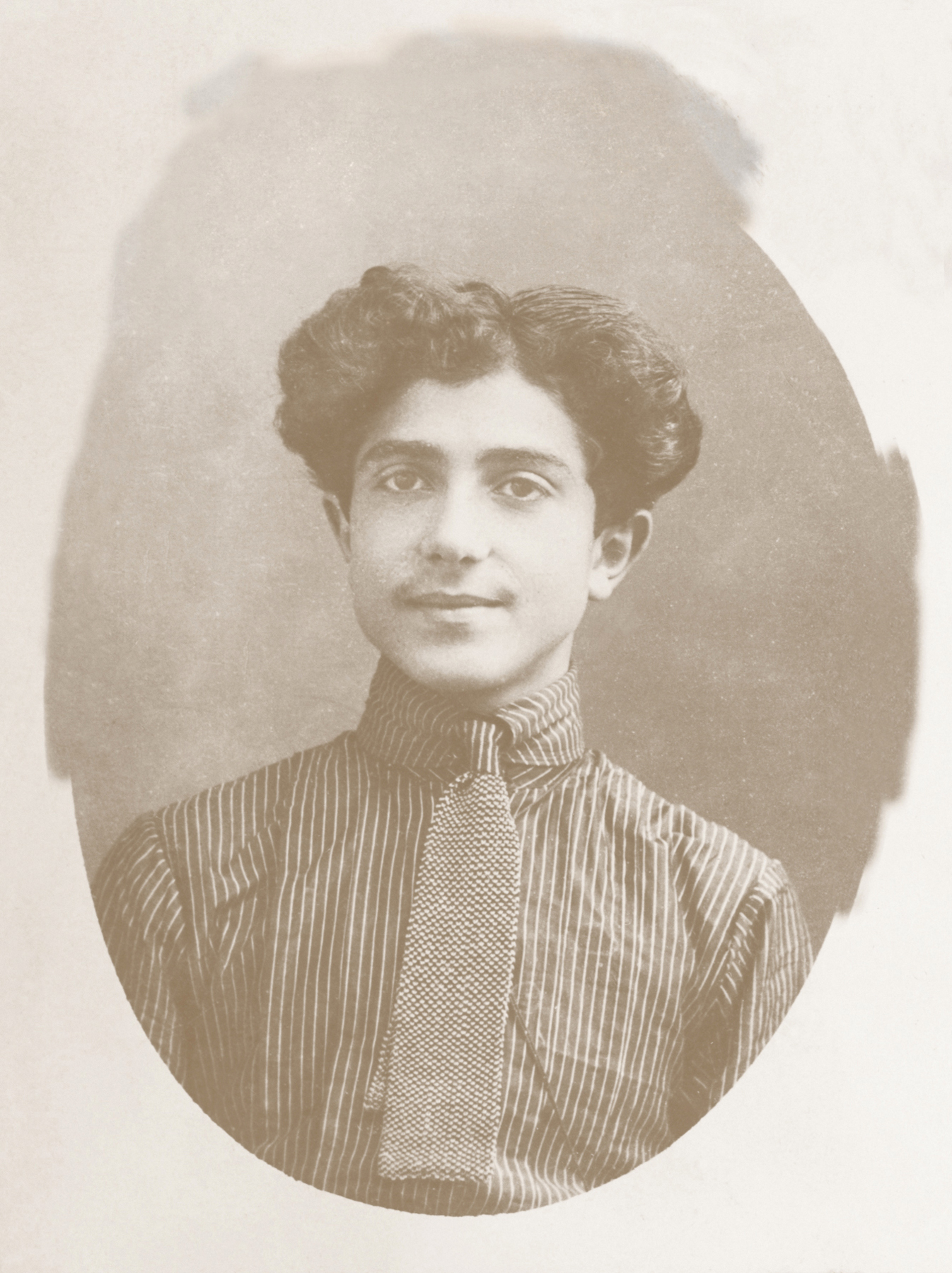

Paulette Brupbacher (1880–1967)

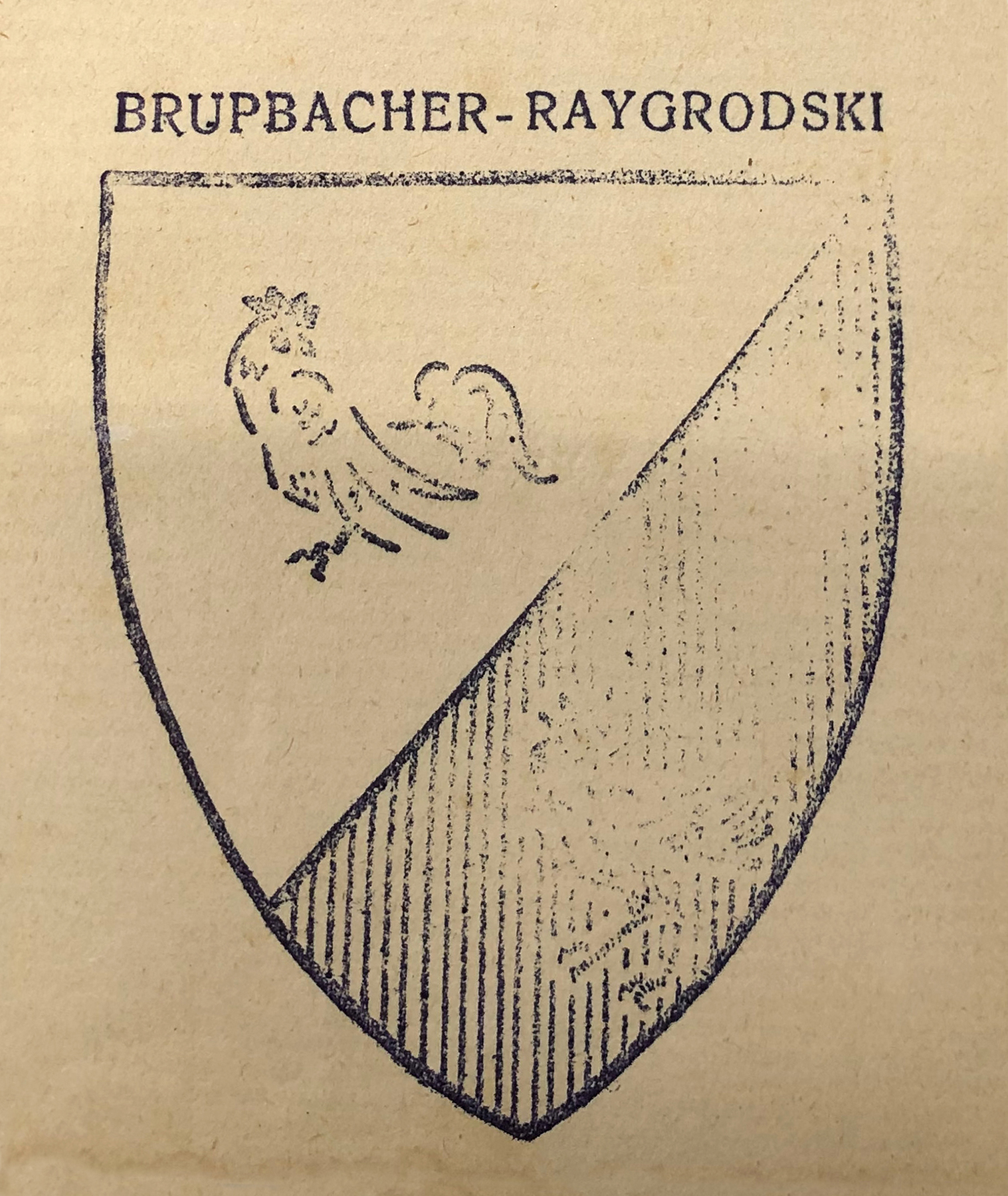

Among the group of politically left-wing members who took a lively interest in developments in the Soviet Union was the anarchist, doctor and women’s-rights activist Paulette Brupbacher. Brupbacherplatz in Zurich is named after Paulette and her husband Fritz Brupbacher (1874–1945).

Paulette Brupbacher was born Pelta Rajgrodskaja in what is now the Republic of Belarus. She moved to Switzerland with her first husband, as it meant she could study there as a woman. After studying philosophy in Bern, she studied medicine in Berlin and Geneva. She married her second husband, the doctor and anarchist Fritz Brupbacher, in 1924. Together, they ran a medical practice in the working-class district of Aussersihl in Zurich. After her husband’s death, she continued the practice until 1952.

While Fritz joined the RBC as early as 1927, Paulette was not listed as a member until 1944. She donated several books from her own collection to the library.

Boris Dreiding (1893–1954)

Among the first members of the RBC was Boris Dreiding, a prisoner of war who founded a perfumery dynasty in Zurich.

Dreiding came from what is today the Republic of Moldova. He was interested in cosmetics from an early age and began training as a pharmacist. He decided to go to Paris, but while travelling there, the First World War broke out and he was taken prisoner. From an Austrian internment camp he reached Switzerland, where he quickly gained a foothold.

At first, Dreiding worked as a bottle cleaner in Ernst Osswald’s grocery shop in Zurich, but soon he was responsible for the entire chemist section. Dreiding manufactured his own cosmetic products, the formulas of which he had been able to save – sewn into the hem of his jacket – when he fled. In 1921, he opened his first perfumery at Bahnhofstrasse 24, Zurich, which still exists today (now at Bahnhofstrasse 17) and is named after his patron, Osswald.

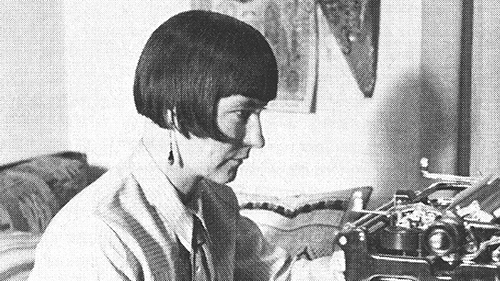

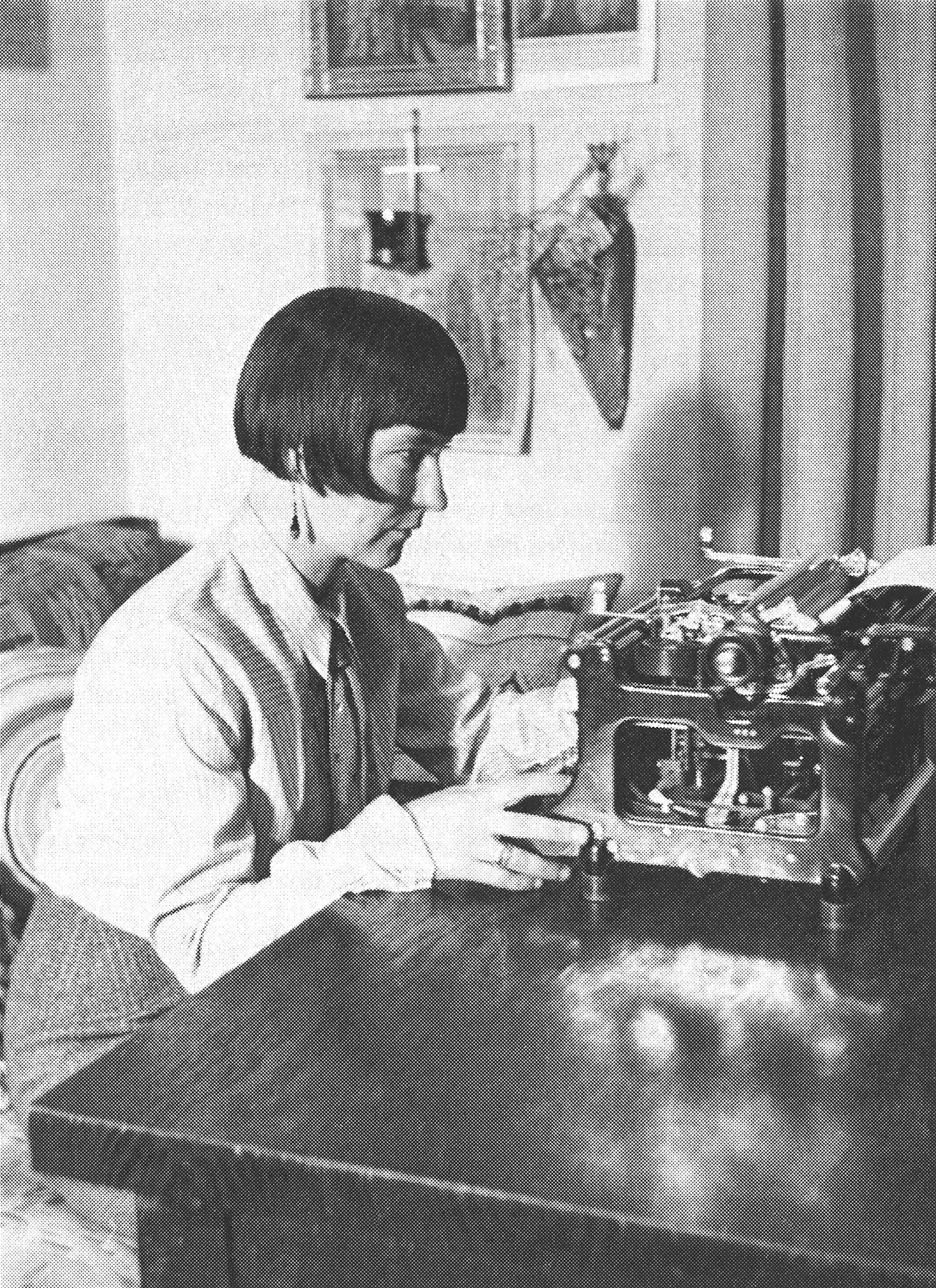

Alja Rachmanova (1898–1991)

The RBC’s members included numerous authors, publicists and translators. Among them was Alja Rachmanova,

born Galina Dyuragina, a successful writer who grew up in an upper middle-class household in the southern Urals. During the Russian Civil War, her family fled to Irkutsk. Dyuragina began studying psychology and married the Austrian prisoner of war Arnulf von Hoyer (1892–1970). In 1926, the couple was expelled from the Soviet Union and settled in Austria. At the end of the Second World War, during which their only son was killed in action against the Red Army, the couple fled to Switzerland. After a stay in Winterthur, they lived in Ettenhausen, in the canton of Thurgau.

Dyuragina always kept a diary about her difficult life, which was marked by flight and displacement. Her notes provided the material for her autobiographical writings, which her husband translated from Russian into German. With her bestsellers, which she published under the pseudonym Alja Rachmanova, she reached numerous readers during her lifetime.

After moving to Ettenhausen, Rachmanova and her husband became members of the RBC in 1949. In addition to Rachmanova’s own books, the Zentralbibliothek Zürich holds other titles in Slavic languages from her archive.

Ivan Ilʹin (1883–1954)

Even though the RBC professed political neutrality, its members included many Russian emigrants who were decidedly anti-Bolshevik. Among the most controversial figures was the conservative religious and political philosopher Ivan Ilyin, who lived in Zollikon for many years and was an active member of the RBC.

After studying law and philosophy in Moscow, Ilyin received his doctorate in 1918, writing his thesis on the German philosopher Hegel. During the Russian Civil War, he joined the struggle against the Red Army of the Bolsheviks and was expelled from Soviet Russia in 1922. He travelled to Germany on one of the ‘philosophers’ ships’, as they were known. His major work, On Resisting Evil By Force, was published in 1925.

In the wake of the National Socialists coming to power, Ilyin went to Switzerland in 1938, where he settled in Zollikon. In secret, he worked on a constitution for post-communist Russia, which envisaged a religion-based autocracy. The renewed interest in his theories under Vladimir Putin led to his remains being transferred from Zollikon to Moscow in 2005.

In 1940, Ilyin became a member of the RBC, which he visited regularly. Several of his works can be found in the RBC’s collection. He and his wife Natalya also donated titles from their own collection to the RBC.

Aleksandr Solženicyn (1918–2008)

The RBC was even able to count some Soviet dissidents among its members. The best-known among them was Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. He became a member of the RBC during his short stay in Zurich.

Solzhenitsyn was a mathematician by training. He fought in the Red Army during the Second World War, before being sentenced by a Soviet court in February 1945 to eight years’ imprisonment and subsequent exile. He later wrote about his time in the Gulag labour camps. His unsparing descriptions of the Soviet regime of injustice brought him worldwide fame. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1970.

After the publication of his epic work The Gulag Archipelago in the West in 1973, Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Union. In 1974, he moved with his family to Zurich, where he immediately became a member of the RBC. Just two years later, he settled in the USA but remained critical of Western democracies. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, he returned to Russia and was exonerated by Vladimir Putin.

He donated two editions of The Gulag Archipelago to the RBC. The volumes are now lost; the RBC archives only contain copies of Solzhenitsyn’s dedications to the association, whose work he greatly appreciated.

Collections

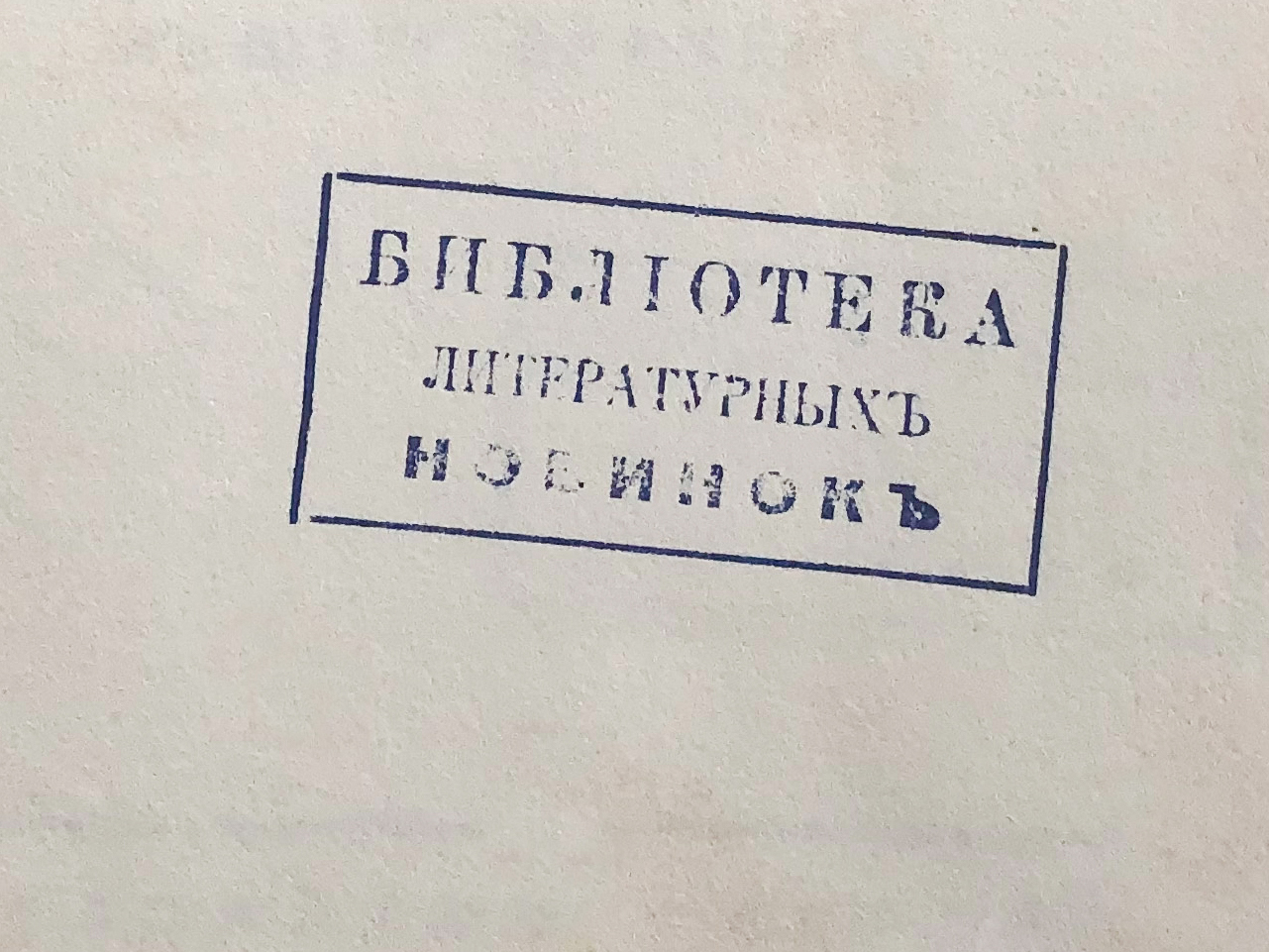

At the end of its existence, the RBC had around 6,000 titles – all of them neatly enclosed in brown wrapping paper. In addition to a diverse selection of light fiction there was historical and cultural-historical literature, as well as regional studies, memoirs and biographies, and some 300 children’s books.

Many of the books dated back to the Russian Empire. The collection is clearly dominated by the Russian classics of the 19th century: the works of Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–1881) and Leo Tolstoy (1828–1910) filled entire shelves.

Despite operating on a consistently tight budget, the librarians endeavoured to acquire contemporary works and new publications. Here, too, the claim of political neutrality applied. Thus, in addition to works by emigrants, they acquired works by modern writers from the Soviet Union.

This set the RBC apart from the other historical Russian libraries in Switzerland that had been established in the 19th century. Consequently, the collection included not just Russian-language emigrant literature and works by Soviet dissidents but also texts by 20th-century literary figures who endorsed the State.

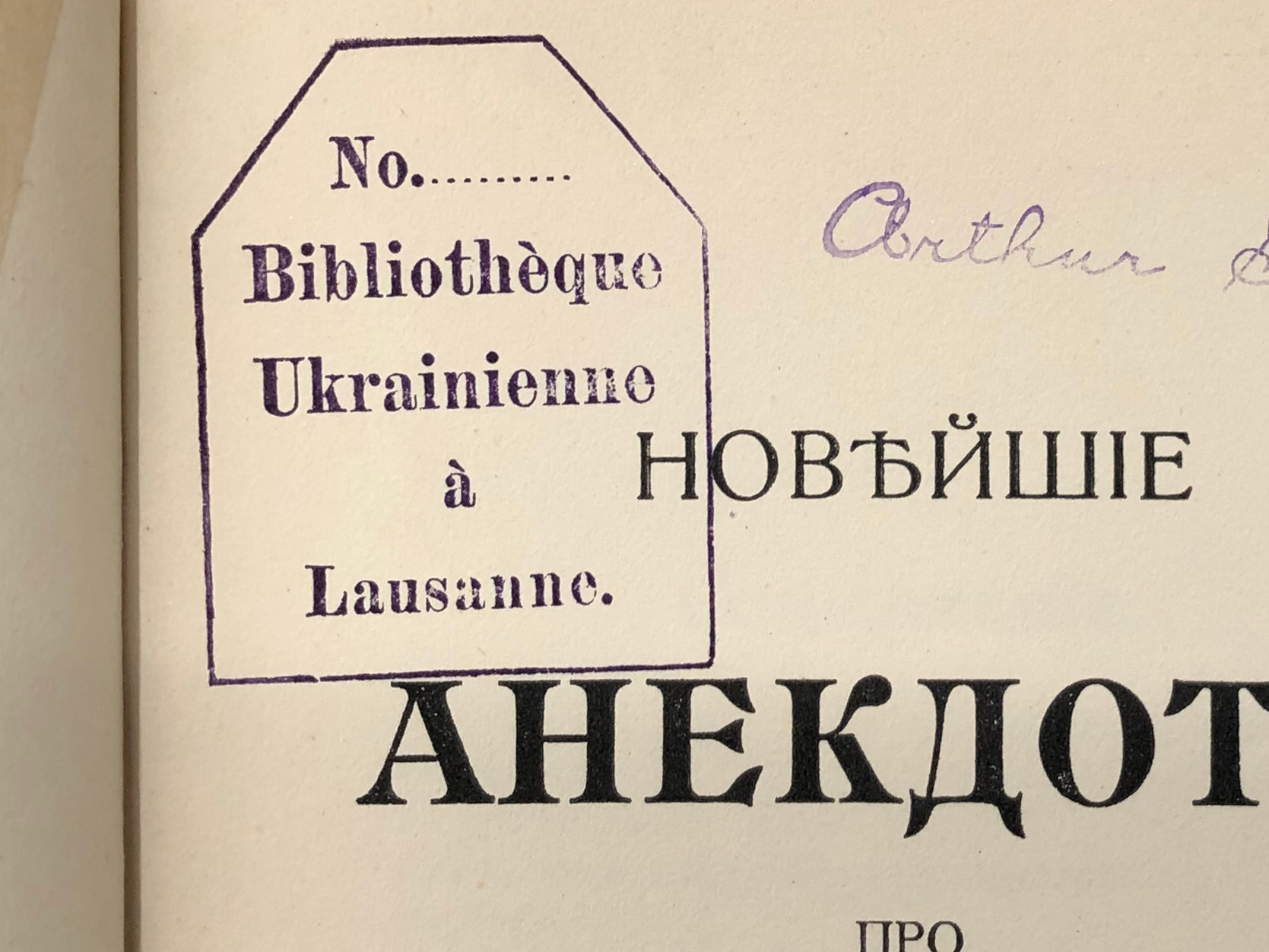

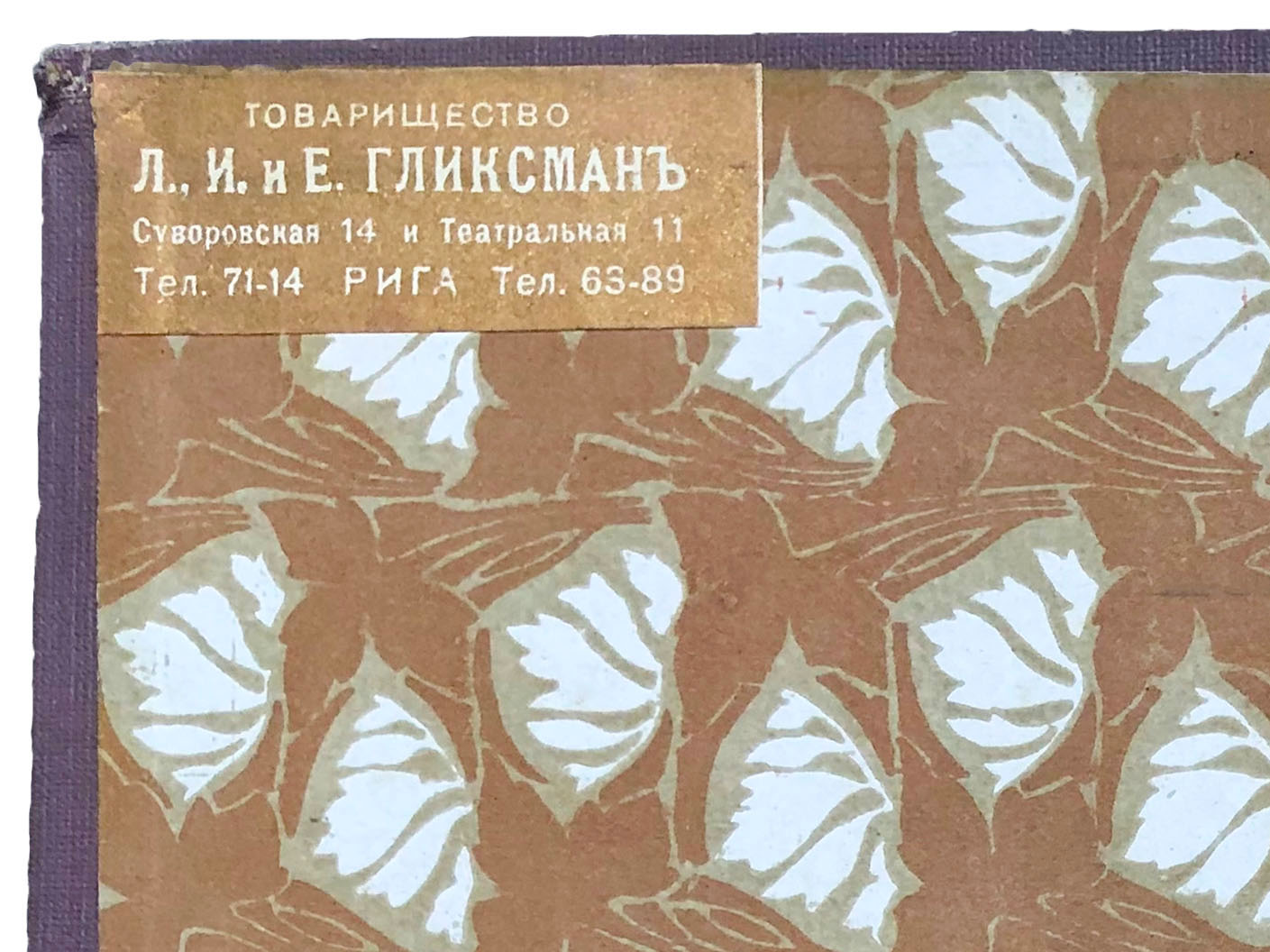

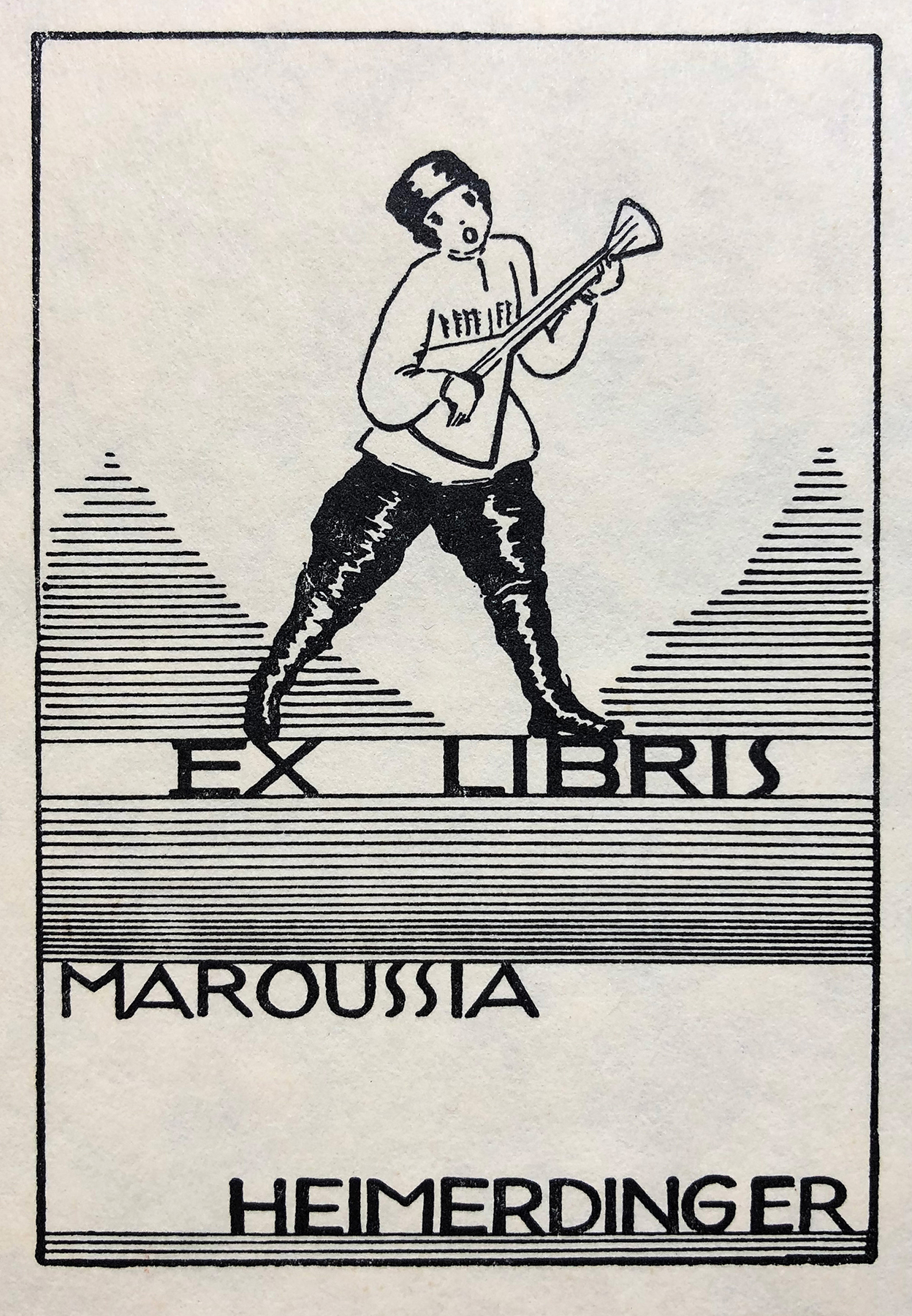

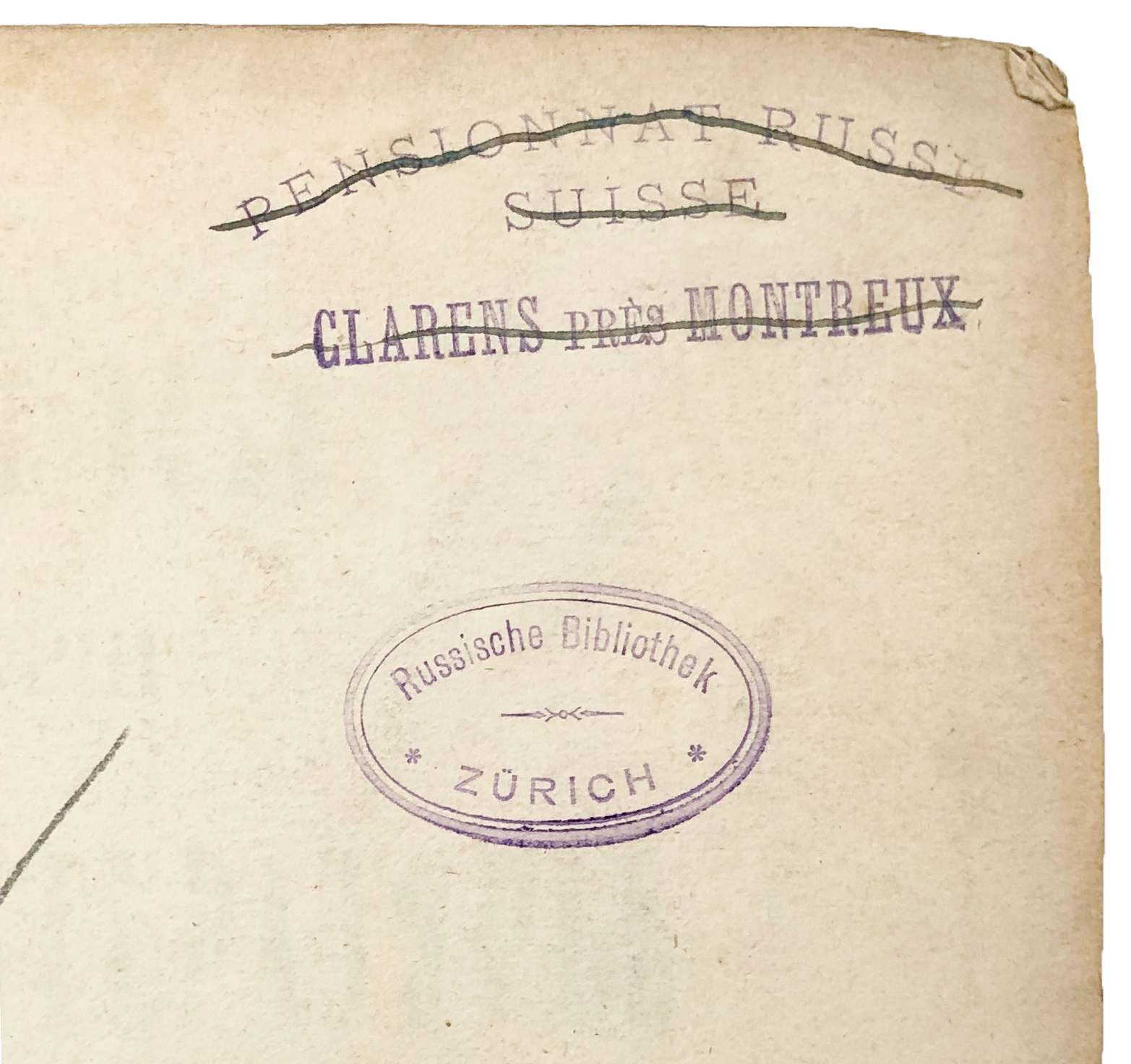

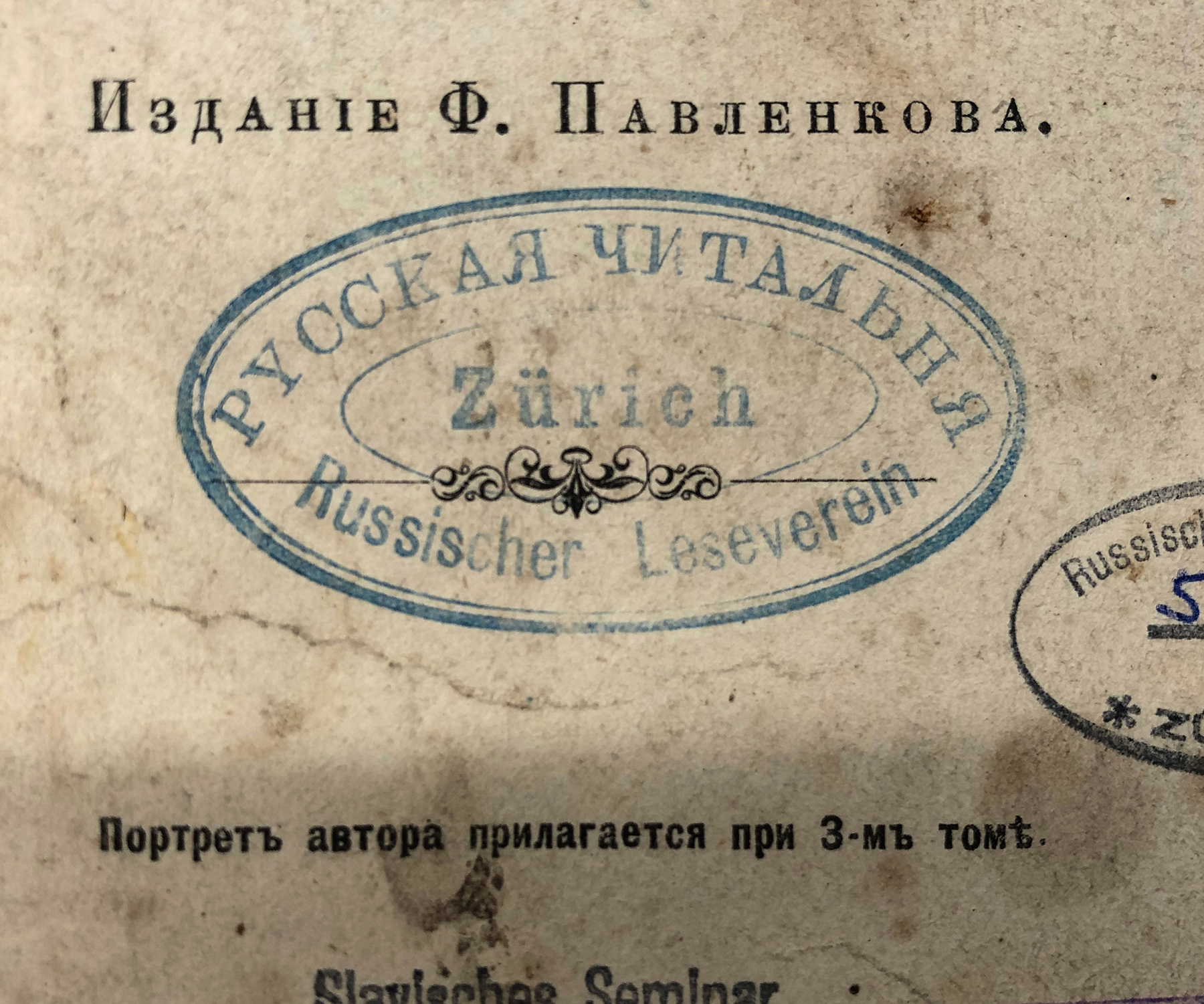

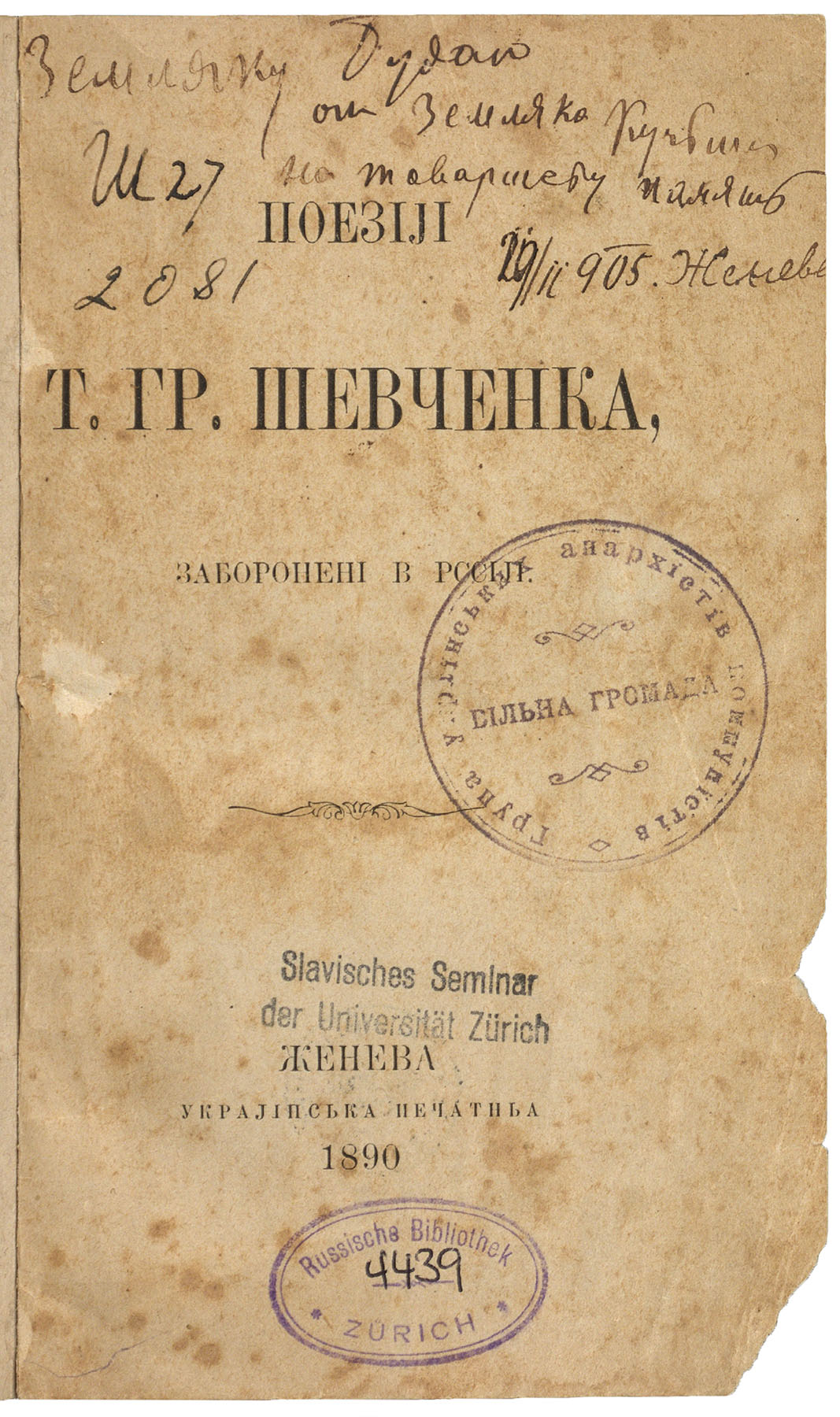

The books were acquired for the RBC partly new, partly from antiquarian sources, and many were also donated to the library. Dedications and notes by the previous owners are evidence of this. Artistically designed bookplates and stamps indicate the long journey of some volumes. For example, several books in the RBC’s collection come from the city of Harbin, a former Russian settlement that now belongs to the People’s Republic of China.

Russian-speakers can still borrow books from the Russian Library Zurich. The following reading recommendations exemplify different aspects of the collection.

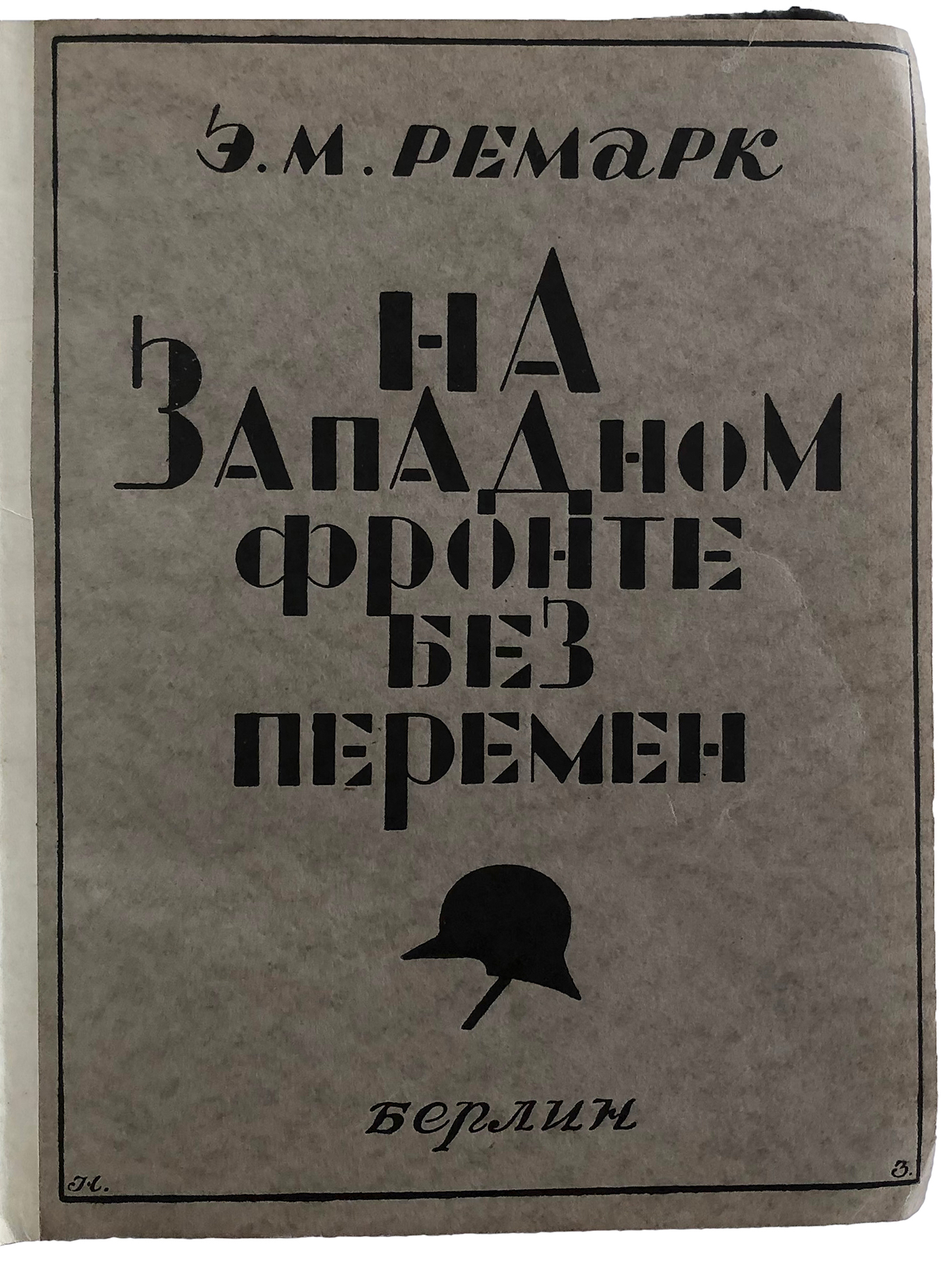

Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front

The focus of the RBC was on Russian literature. However, the library also held works by Western authors that had been translated into Russian. These included German-language writers like Heinrich Mann (1871–1950), Heinrich Böll (1917–1985) and Erich Maria Remarque (1898–1970).

Ten years after the end of the First World War, Remarque wrote his novel All Quiet on the Western Front about the horrors of war. The anti-war novel is about the tragic fate of a young German soldier on the Western Front and was an immediate success upon publication. In the same year of its publication, it was translated into 26 languages, including Russian.

The RBC owned a copy of the ‘only authorised and complete Russian edition’ from 1928, as can be seen from the title page. The book was published not in Moscow or Leningrad but in Berlin. An active scene of Russian-language publishers had formed there during the Weimar Republic.

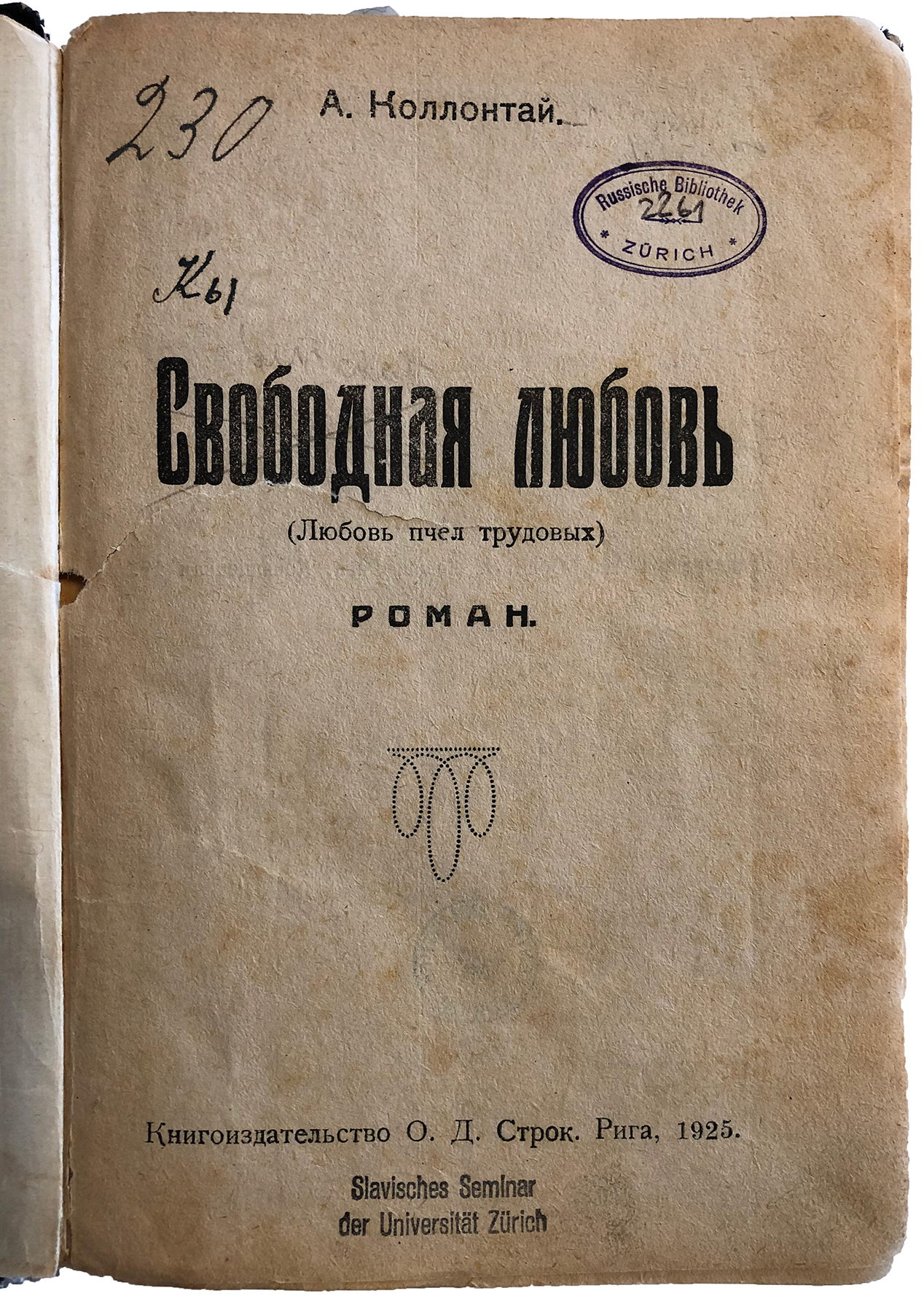

Alexandra Kollontai’s Free Love

Male writers predominate in the RBC’s collection. However, female authors who held progressive views and led unconventional lives are also represented. These include the poets Anna Akhmatova (1889–1966) and Zinaida Gippius (1869–1945), and the writers Elsa Triolet (1896–1970) and Alexandra Kollontai (1872–1952).

Kollontai was one of the pioneers of female equality in the early Soviet Union. She studied at the University of Zurich in 1898, later living in exile in Germany, France and Scandinavia. Under Lenin and later Stalin, she made a political career; as the first female People’s Commissar (as ministers were called in the Soviet Union), Kollontai campaigned for maternity rights, childcare, legal access to abortion and the loosening of marriage laws.

During her later work as the world’s first female diplomat, she published stories featuring her ideas about free love between men and women. These included the volume Love of Worker Bees, which was first published in 1923.

A story from the volume was published in Riga in 1925 under the title Free Love. A copy made it to the RBC in the early 1930s and was regularly borrowed until the late 1960s.

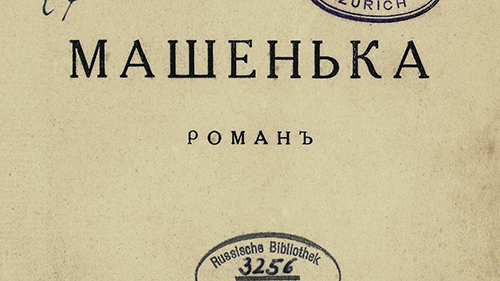

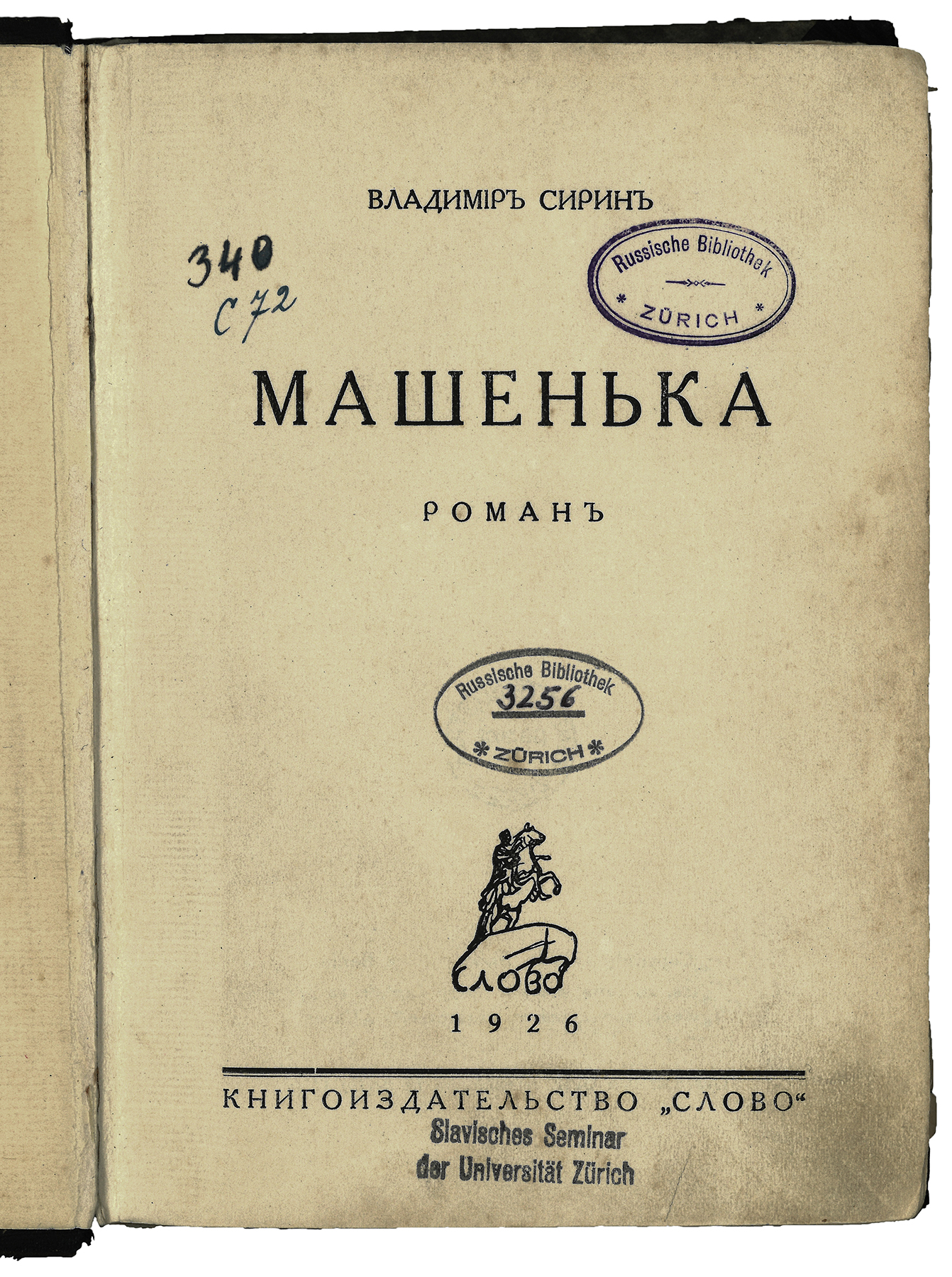

Vladimir Nabokov’s Mašenʹka

The works of authors who had left Russia and the disintegrating Russian Empire after the October Revolution and who were now writing in exile were particularly popular at the RBC. Among those authors were Mikhail Osorgin (1878–1942) and Ivan Bunin (1870–1953), both of whom had emigrated to France. Along with Paris, Berlin became an important centre for Russian exiles. Vladimir Nabokov (1899–1977) and his family also settled in the city after fleeing Soviet Russia.

Under the pseudonym Vladimir Sirin, Nabokov published his first novel, Mašenʹka (Mary), here. Set in Berlin in the early 1920s, it describes the life of the Russian emigrant Lev Ganin, who longingly remembers a lost love and the homeland he left behind. The novel was first published in 1926 by Slovo (Das Wort), a publishing house founded by Russian emigrants in Berlin.

The RBC copy – a first edition – has been in the collection since 1927 and is thus one of the first contemporary works of exile literature acquired by the association.

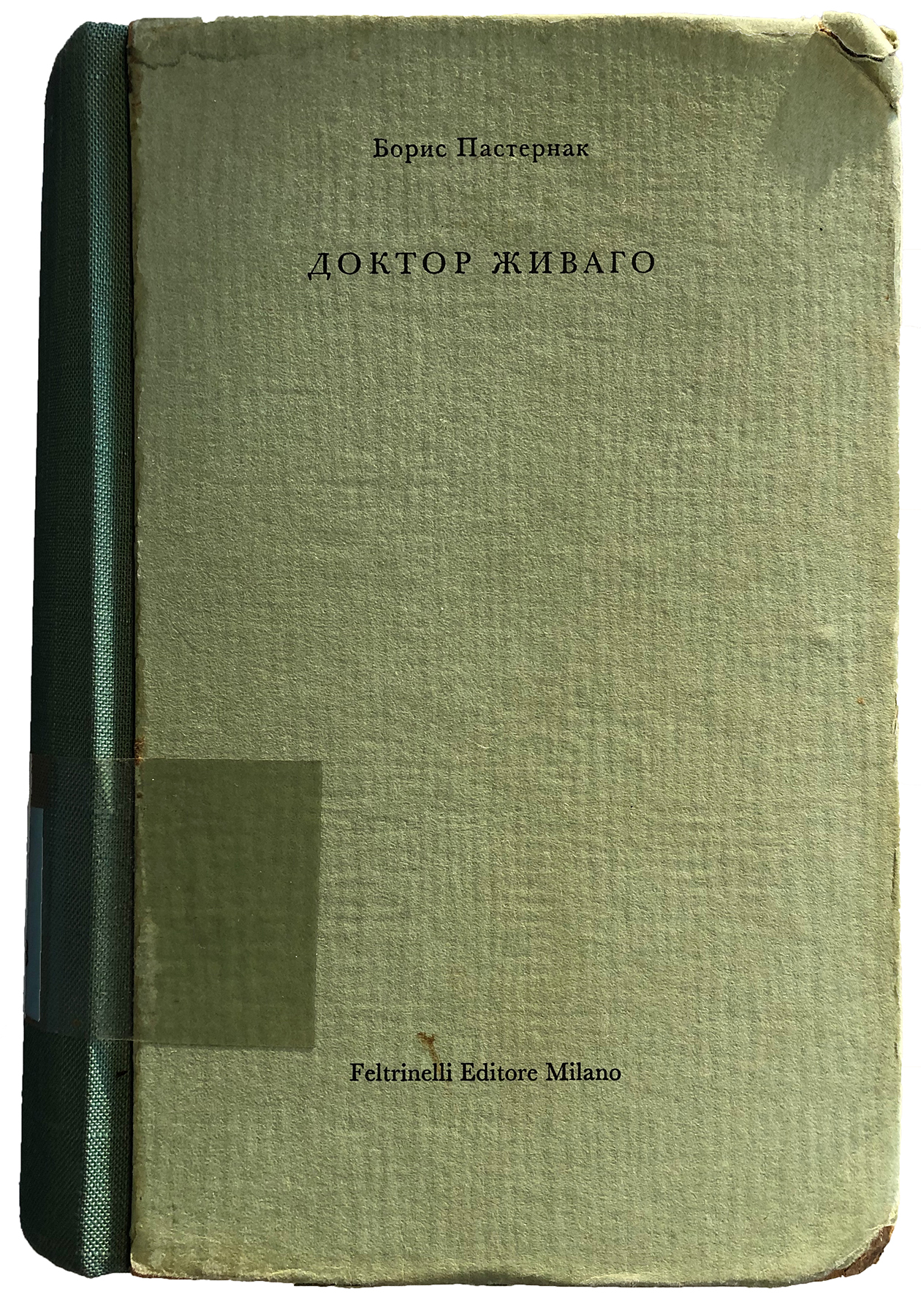

Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago

RBC readers could also obtain literature from the Soviet Union, including examples of socialist realism. Prototypical of the State-imposed style was the novel How the Steel Was Tempered (1932) by Nikolai Ostrovsky (1904–1936), which was available in three editions in the RBC.

More strongly represented, however, were those Soviet writers who, despite the threat of reprisals, stood in open or covert opposition to the State. These included Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940) from Kyiv and Andrei Platonov (1899–1951), whose novels were not allowed to be published in the Soviet Union during the authors’ lifetime. The novel of the century, Doctor Zhivago, for which Boris Pasternak (1890–1960) received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958, was also not published in the Soviet Union at first. The novel tells the eventful love story of Lara Antipova and the poet doctor Yuri Zhivago against the backdrop of the historical upheavals in 20th-century Russia.

Pasternak was able to smuggle a copy of the manuscript, which he had completed in 1955, to the West. Doctor Zhivago was first published in Italian in November 1957 by the publishing house Giangiacomo Feltrinelli Editore in Milan. An edition in the original Russian followed soon after that. The RBC holds one of those early Russian editions from Feltrinelli from the late 1950s.

Taras Shevchenko’s Kobzar

The RBC was a library for Russian-language literature. However, this did not mean that all authors who wrote in Russian were also ethnic Russians. There were also Russian-language works by writers from other Slavic nations and even a few books in other Slavic languages, such as Ukrainian.

One such example was the work of the most important Ukrainian poet of the 19th century, Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861). He was born a serf in the Kyiv Governorate, which, at the time, belonged to the Russian Empire. Only after being freed by wealthy patrons was Shevchenko able to begin studying at the Academy of Arts in Saint Petersburg, but he increasingly devoted himself to writing. His first volume of poetry, Kobzar, appeared in 1840 and was met with an enthusiastic response. It is considered a milestone in Ukrainian literature.

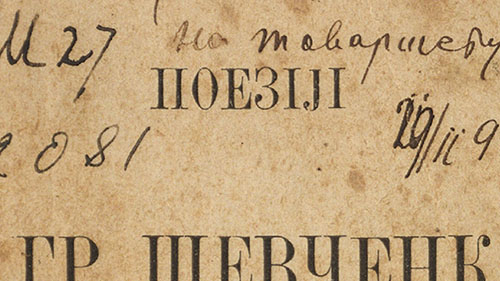

The RBC holds several editions of Kobzar, as well as other volumes of his poetry that were published in Moscow, but also in Kyiv. There is even a copy from a Ukrainian printing house in Geneva from 1890. In the preface, the unknown author explains that this edition contains poems from Kobzar, which were banned by the Russian censor. A stamp on the title page indicates that the volume formerly belonged to a group of Ukrainian anarchist communists.

The first and only Russian library?

The name ‘The Russian Library Zurich’ makes sense, since it describes the only declared purpose of the association. It is unclear, however, whether the founders were aware that their association was in the tradition of an earlier Russian library in Zurich.

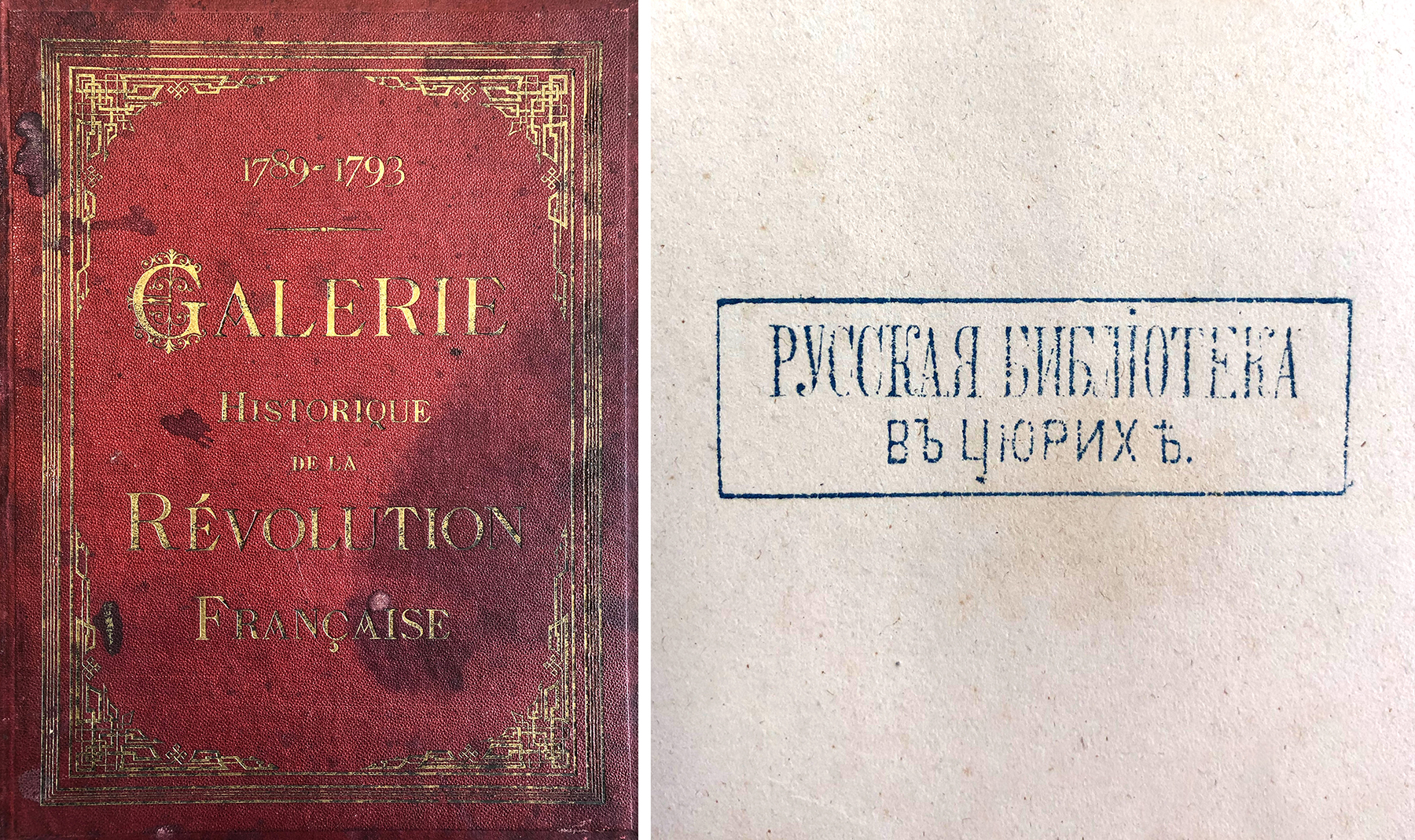

Since the middle of the 19th century, Switzerland had been an important place of refuge for numerous political opposition figures from the Russian Empire. Others came to study here or to seek treatment in the sanatoriums. The diverse circle of Slav exiles became involved in extensive journalistic work, founding their own printing presses, reading societies and libraries. In Davos, for example, a library for Russian spa guests had existed since 1899. And in Lausanne, the Russian pedagogue and supporter of the Social Revolutionary Party Nikolai Rubakin (1862–1946) had been building a library of no fewer than 75,000 titles since 1907.

The Russian colony in Zurich also had a library of Russian-language works – albeit only briefly – as early as the 19th century. The first Russkaja Biblioteka v Cjuriche was founded in 1870. It focused on publications on the national workers’, liberation and revolutionary movements. In 1873, a declaration by the Tsar severely restricting opportunities for female Russian students in Zurich led to the decline of the city’s Russian colony. The library also closed down and the collection was dispersed; the whereabouts of the books can only be traced in individual cases.

One title held by this first Russian library in Zurich was donated to the Zentralbibliothek and is now in the Rare Books Collection.

The fate of the RBC – from the Slavic Studies Department of the UZH to the Zentralbibliothek

In the last years of the RBC’s existence, the volunteer librarians expressed concern about the fate of the library, since the readership was only small and featured few young people. While more and more students of Slavic studies joined after the Slavic Studies Department was established at the University of Zurich in 1961, this did not compensate for the lack of active young members.

From 1980 onwards, the question of the library’s fate became increasingly urgent. The board considered various options, such as selling the collection to private individuals or handing it over to the Zentralbibliothek. In 1983, the Association of the Russian Library Zurich finally donated the collection of around 6,000 volumes, valued at 45,000 Swiss francs, to the Slavic Studies Department of the University of Zurich.

![Transport of the RBC’s collection to the Slavic Studies Department, 1983. (Picture: anonymous/from: Peter Brang et al. (eds.): Widening the View to the East. Fifty Years of the Slavic Studies Department of the University of Zurich [1961–2011], Zurich 2011).](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/zuerich/russische-bibliothek-zuerich/20230215-TUR-Zuerich-RBC-13.jpg)

In the early 2000s, as the department library continued to grow, the question of where the RBC collection should be located arose again. At the end of 2002, it was decided that it should be given to the Zentralbibliothek and, on 11 January 2003, the first of about seven deliveries was made from the Slavic Studies Department, on Plattenstrasse, to Zähringerplatz. At last, the RBC and the archives of the association had reached their final destination.

The RBC in the ZB Zürich – research tips

- The collection of books with the shelfmark RBC can be searched and ordered online via Swisscovery. Volumes published within the last 100 years can usually be borrowed; older volumes can be accessed in the reading room. Please note the spelling when searching for individual titles or authors: the Russian-Cyrillic alphabet has been transliterated into German according to DIN 1460-1.

Željka Vulović, liaison librarian of Slavic Philology, will be happy to answer questions about the book collection. - The archive of the association is listed in the archive portal zbcollections.ch and can be viewed in the reading room of ZB Zürich’s Manuscript Department. To visit, please contact the Manuscript Department in advance via e-mail.

- A collection of 263 historical postcards is also part of the RBC holdings. It can be viewed in the reading room of the ZB’s Department of Prints and Drawings. To visit, please contact the Department of Prints and Drawings in advance via e-mail.

Miriam Leimer, art historian, Willy-Bretscher-Fellow 2022/23

February 2023, last update March 2025

Header image: RBC books in the ZB Zürich (Stefanie Ehrler)

Special thanks

The author is deeply indebted to Stefanie Ehrler, Turicensia Department at the ZB; Marija Simasek, until 2024 liaison librarian of Slavic Philology at the ZB; Anita Michalak, librarian of the Slavic Studies Department at the UZH; Dr Eva Maurer, head of the Swiss Library of Eastern Europe (SOB) in Bern; and, especially, Monika Bankowski, subject specialist in Slavic Philology at the ZB until 2011.

The research was made possible by the 2022/2023 Willy-Bretscher-Fellowship.