Nägeli’s postbox – Zurich’s music publisher at work

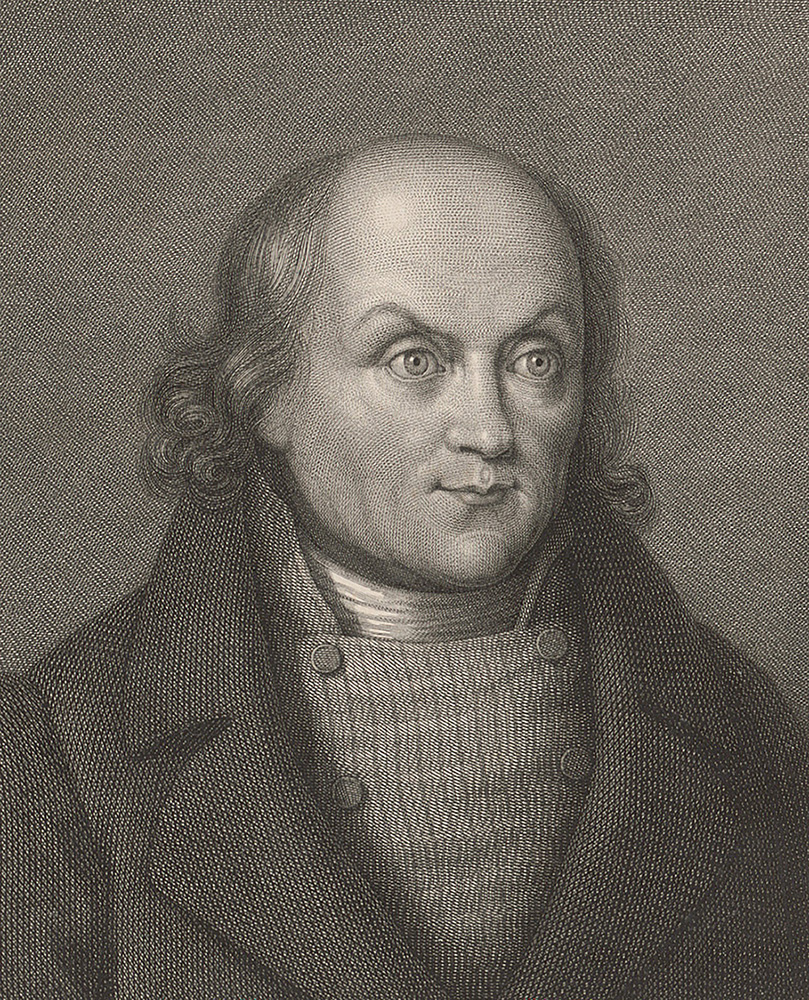

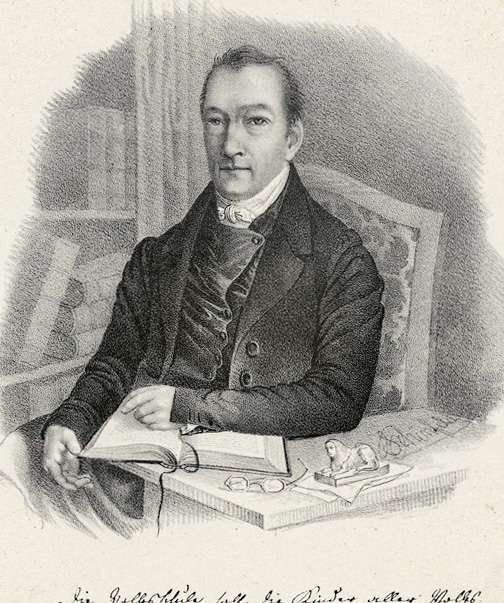

In the early 19th century, Hans Georg Nägeli (1773–1836) was Zurich’s most important music publisher, a busy music teacher and a pugnacious politician. His correspondence, held by Zentralbibliothek Zürich, offers in-depth insights into his world – both professional and social. Nägeli’s letters impacted local and international goings-on and served to disseminate his publications. 2023 marks the 250th anniversary of his birth.

Nägeli’s address book

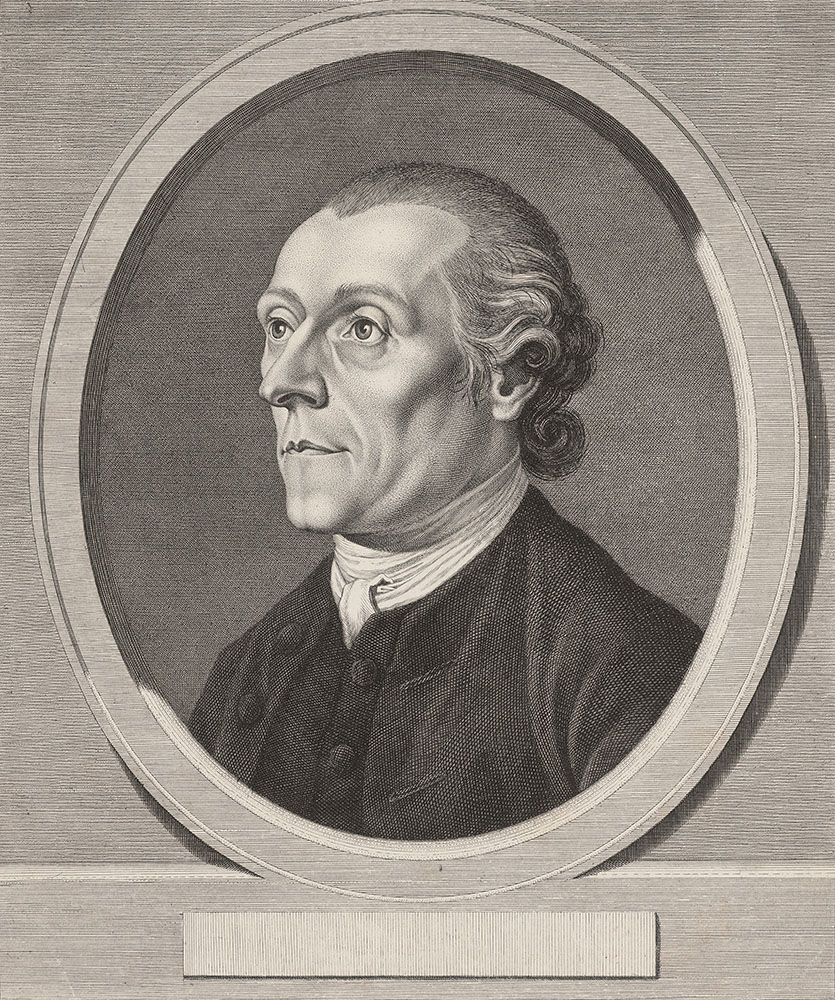

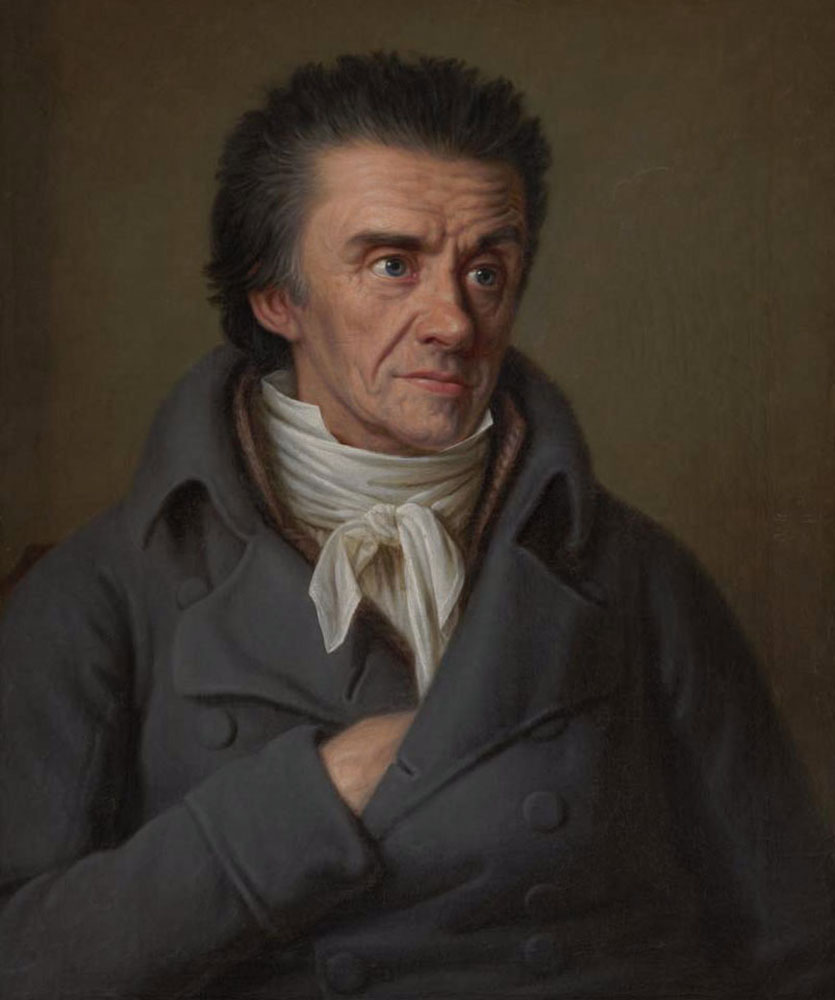

Hans Georg Nägeli’s estate included around 3,000 letters documenting his activities as a business partner, his personal connections and his social endeavours. Friend, publisher, composer and politician – as you read his letters, the array of figurative hats he wore becomes clear: Nägeli described his musical ideas in a letter to Leipzig-based publisher Breitkopf, invited educator Michael Traugott Pfeiffer for a friendly visit and corresponded with his wife, Lisette Rahn, on business matters regarding his sheet music shop in Zurich. He was actively involved in the politics of his day and corresponded with religious figures such as Johann Caspar Lavater.

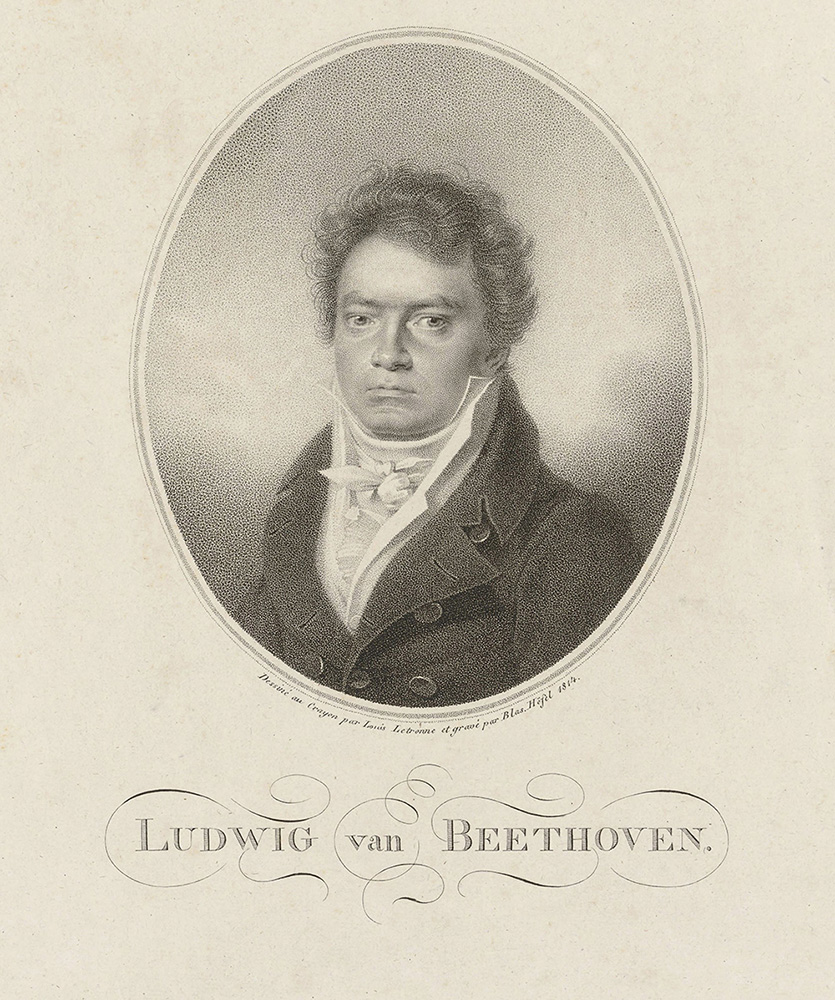

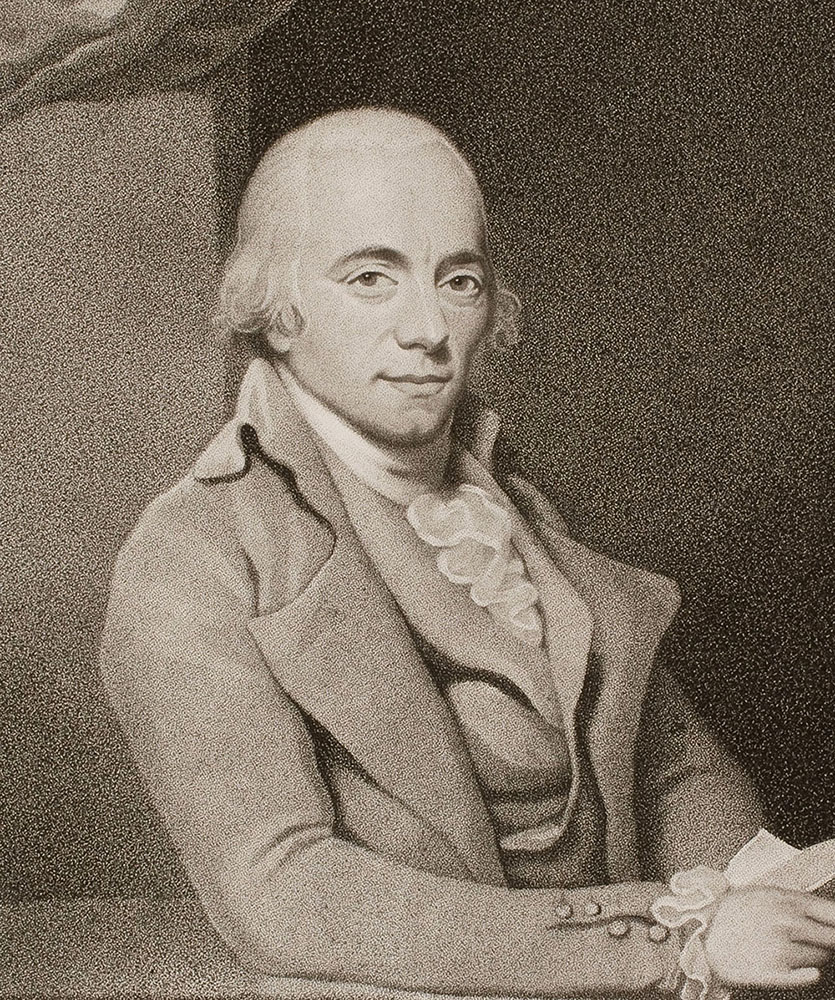

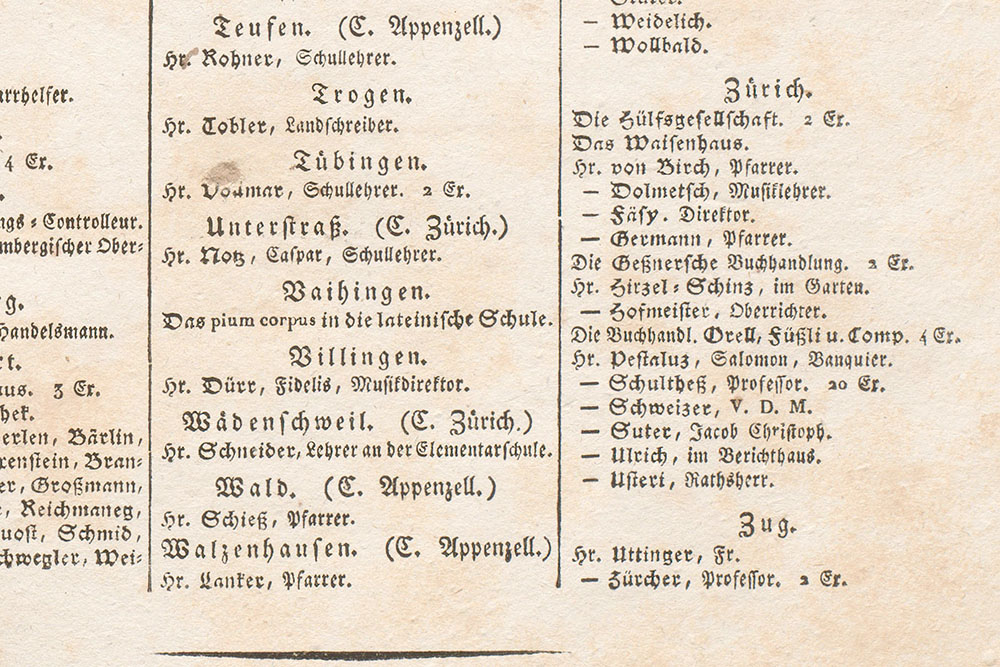

Nägeli’s proverbial address book included hundreds of people, some renowned. His correspondence includes letters from key composers such as Ludwig van Beethoven, Carl Maria von Weber and Muzio Clementi, along with small-scale sheet music retailers. The Zurich-based music teacher was also in frequent communication with Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi and his pupils.

A businessman with a passion for music

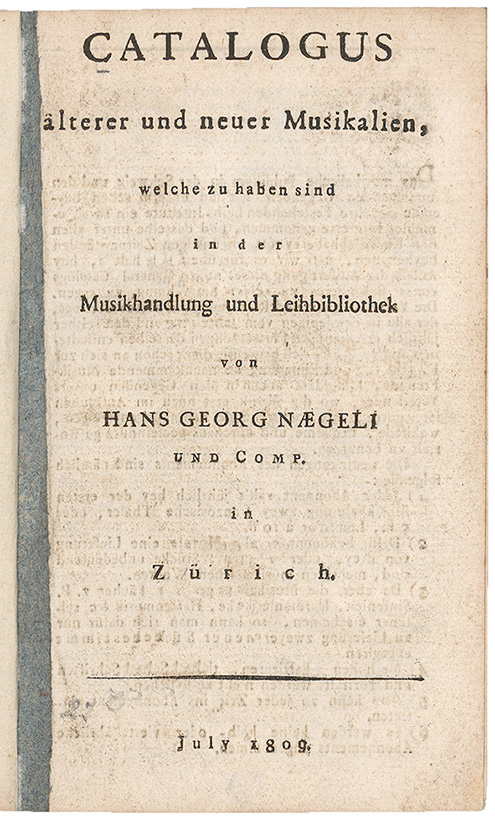

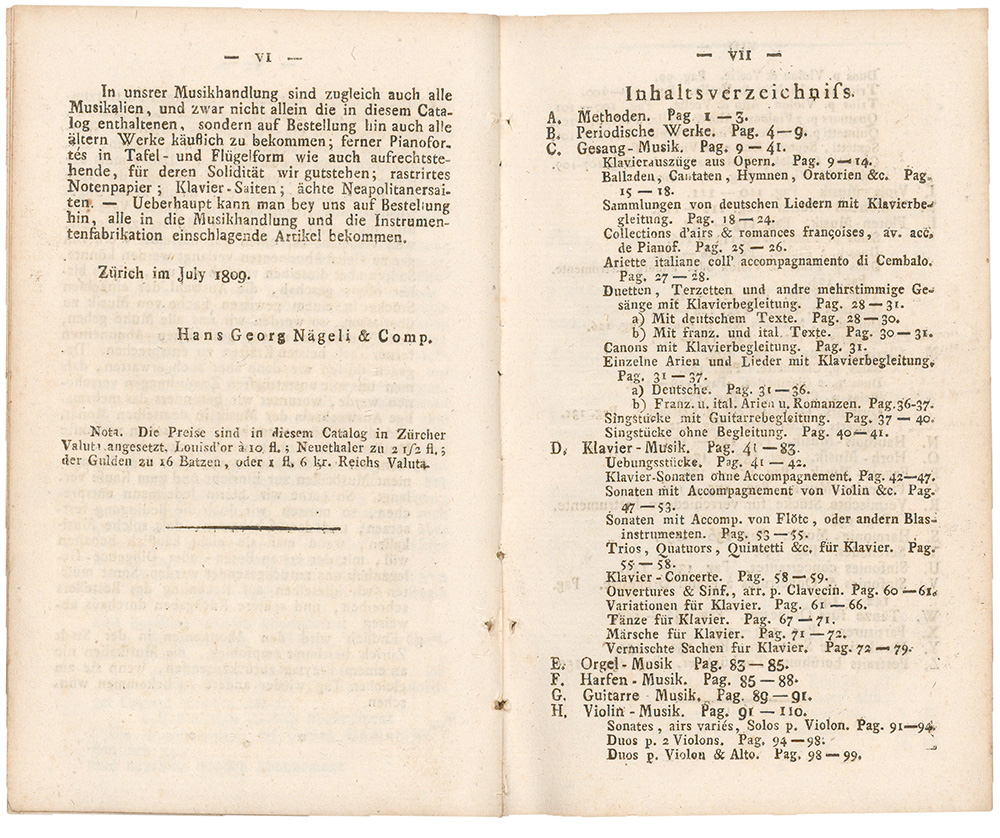

Hans Georg Nägeli set up a music business in Zurich at the tender age of 17. The enterprise comprised a lending library and a sheet music shop, enabling the young man to earn a living while pursuing his passion for music. Thanks to his business relationships with music publishers abroad, he was able to procure sheet music that he was also personally interested in as a musician and composer. He soon began to publish works himself.

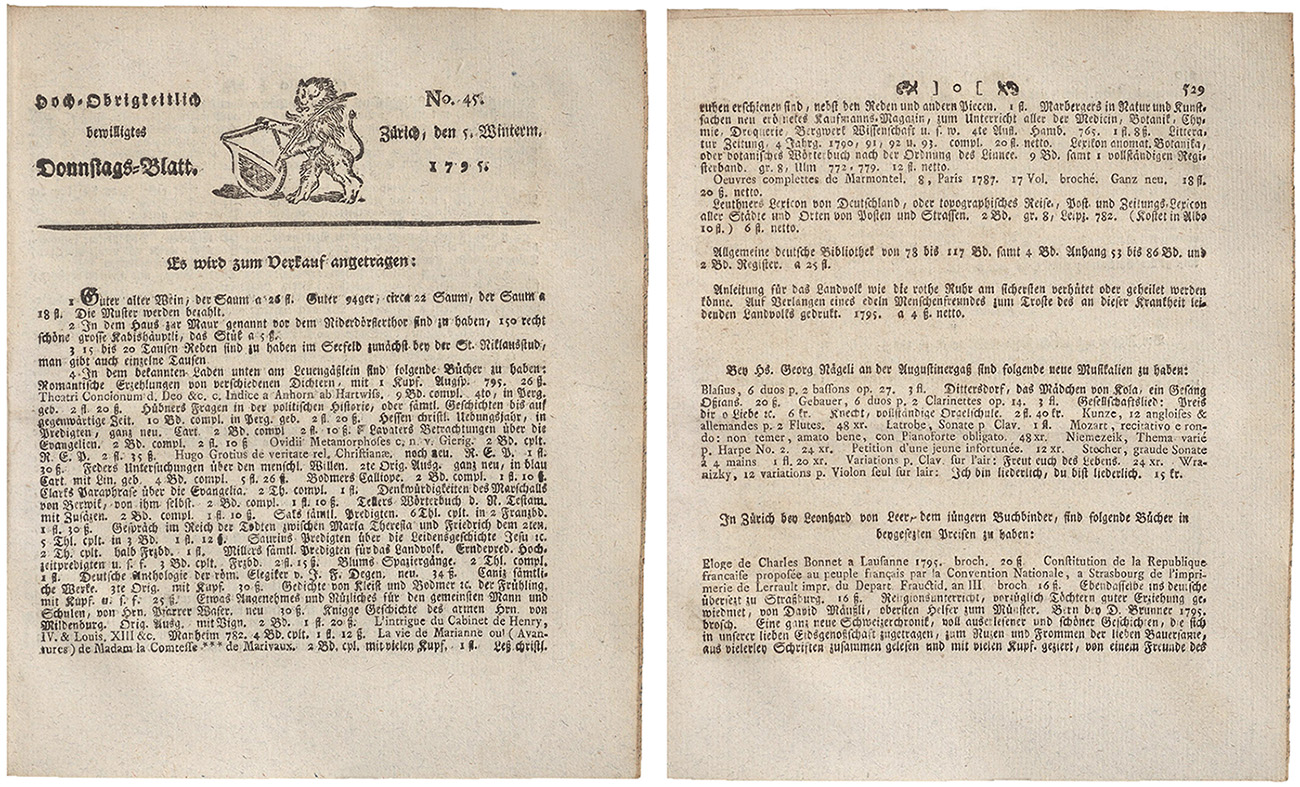

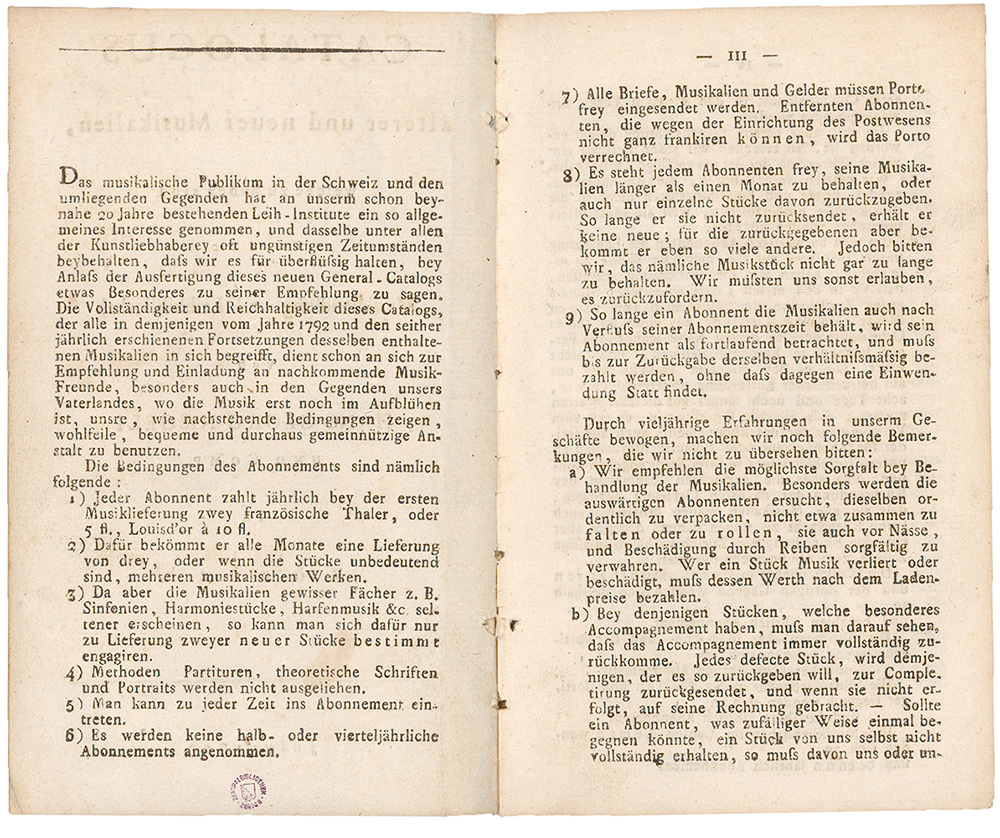

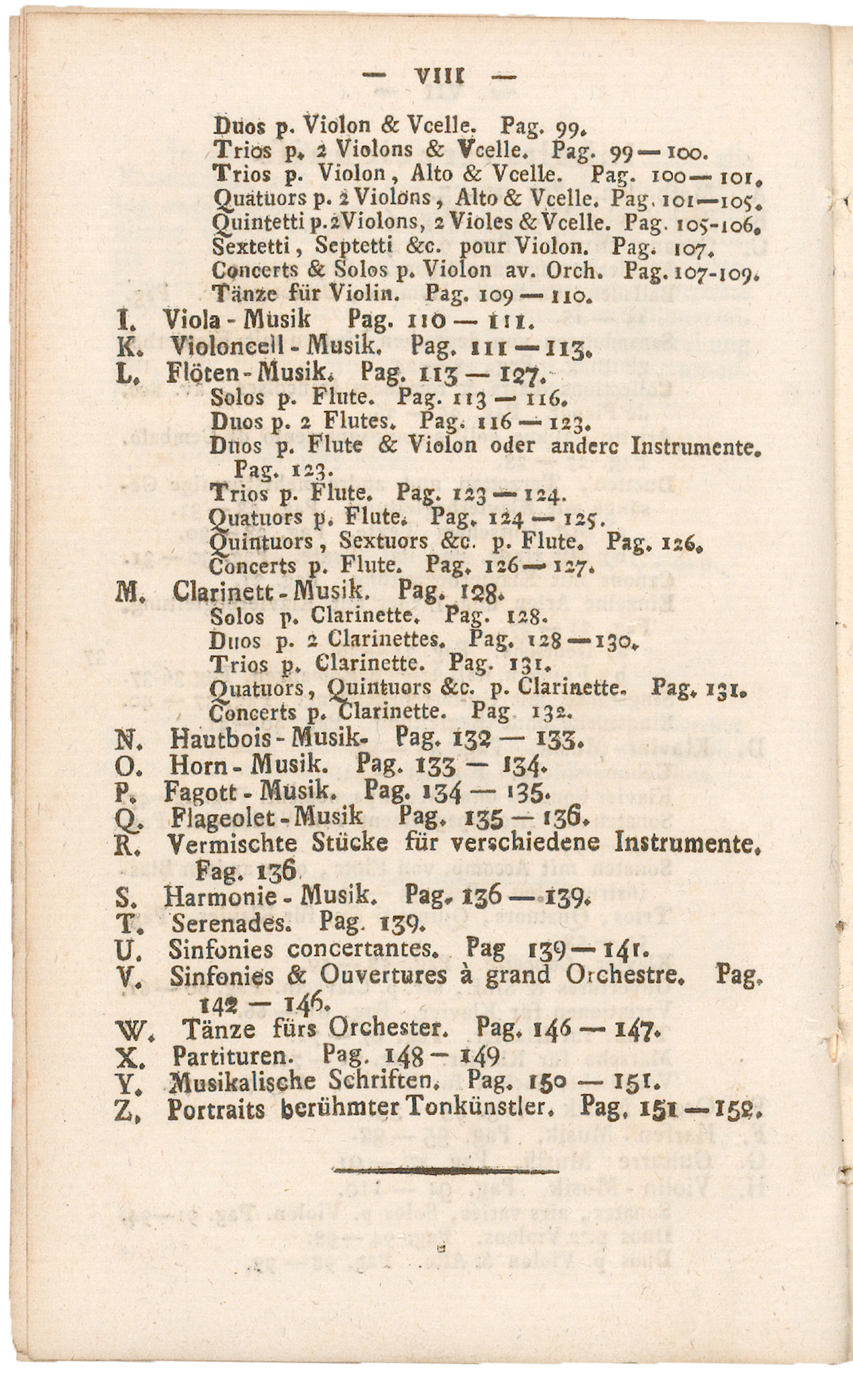

Nägeli’s catalogue listed all the music available from him. As this ‘Catalogue of sheet music old and new’ was only updated once a year, not all the publications listed were actually available, whereas Nägeli published up-to-date weekly adverts for works available in his shop in Zurich’s ‘Donnstags-Blatt’ newspaper.

Nägeli’s enterprise was never solely dedicated to commercial pursuits. The publishing house, in particular, was a passion project. To support it, the young businessman needed substantial financial resources – and the prospects of success were uncertain. It was only possible for him to execute large publishing projects by taking on debt. In return, though, publishers’ programmes helped shape the life of the musical world. Nägeli’s goal was to encourage the general public’s understanding of music: he wanted to make a wide audience aware of challenging works.

Nägeli’s existence as a musical entrepreneur was shaped by highs and lows. The following provides some more information about important milestones in his life.

Birth and childhood

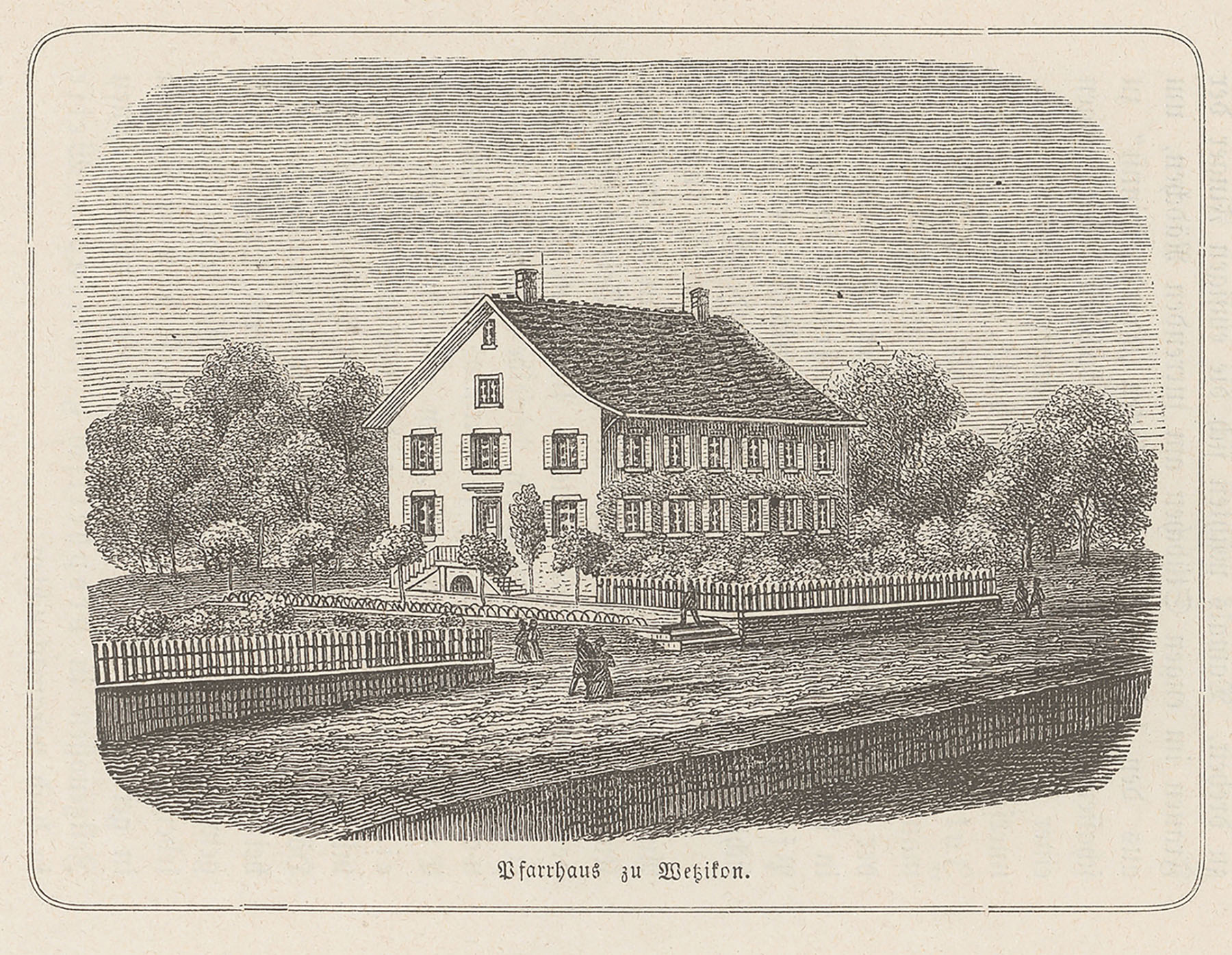

Hans Georg Nägeli was born in Wetzikon, the son of a vicar, and grew up with his siblings in rather modest surroundings. Nägeli had an affinity for music from an early age. Alongside his role in the church, his father was head of the music college in Wetzikon, where the young boy took part in rehearsals and performances. At the tender age of eight, he played ‘fairly difficult sonatas’ on the piano, as Hans Conrad Ott-Usteri puts it in his biography of Nägeli.

Establishment of his business

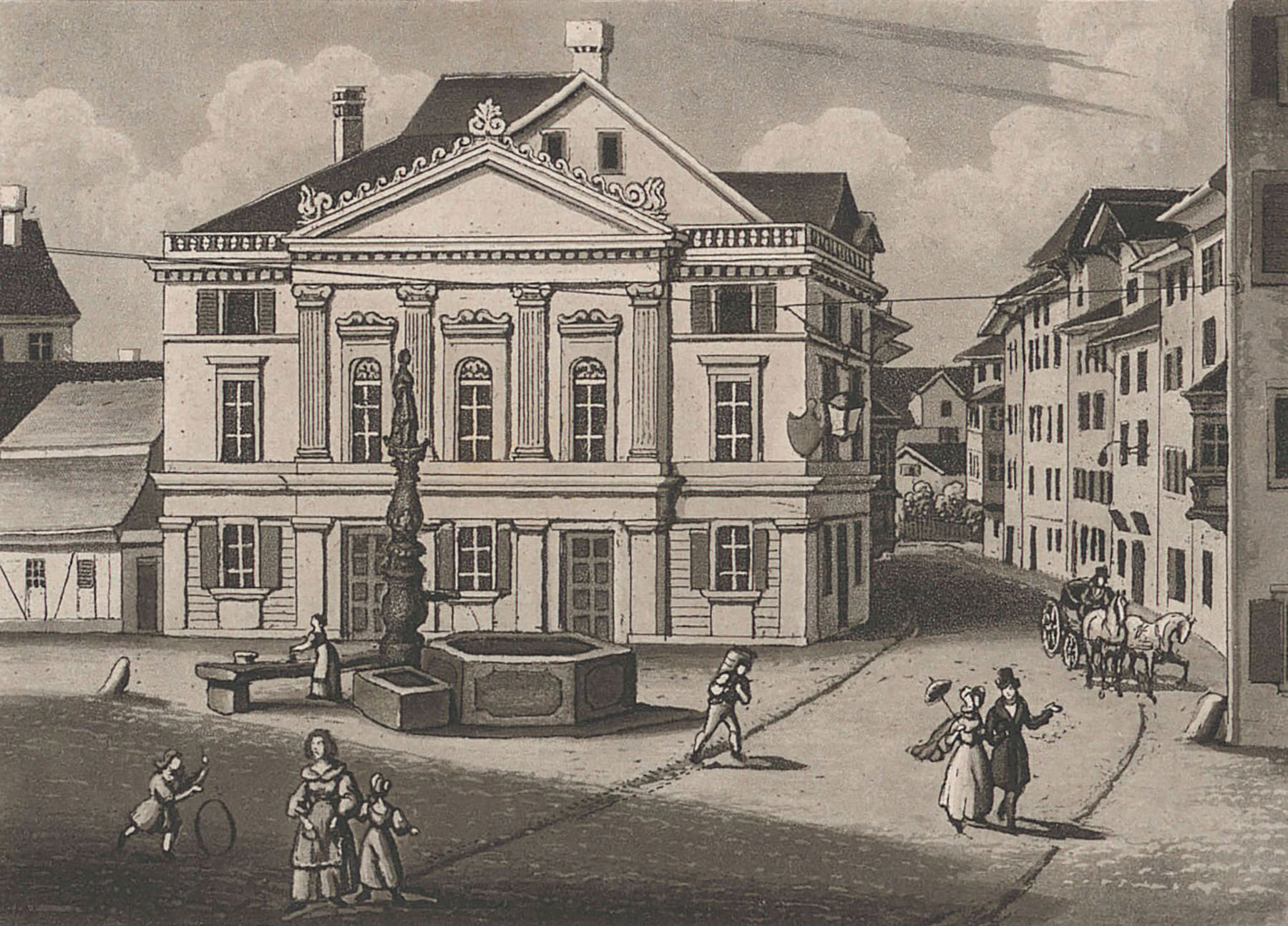

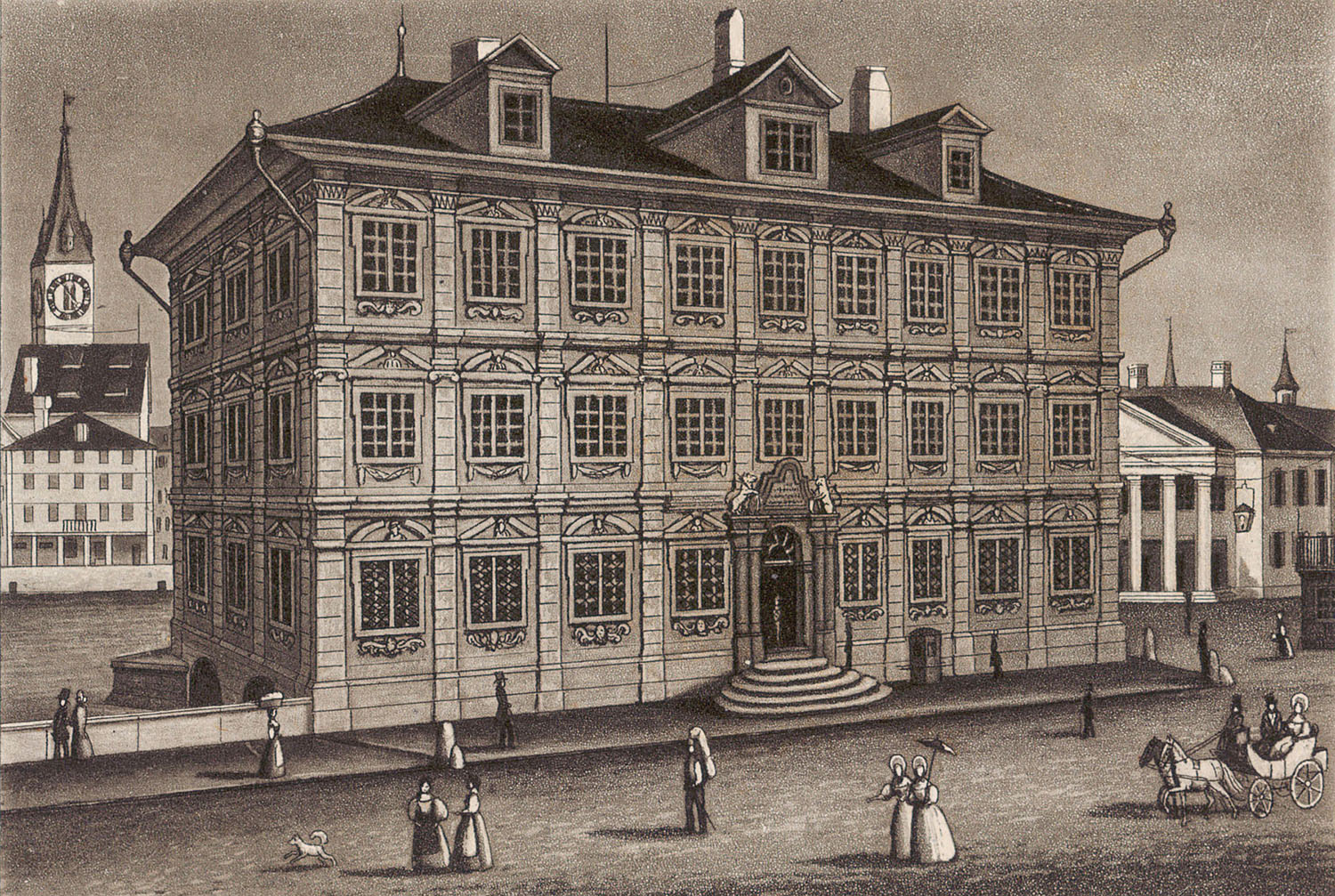

In January 1791, 17-year-old Nägeli set up a sheet music lending library and shop, with the latter’s premises at Augustinergasse 24 in Zurich. In 1794, he added a publishing house to the library and shop as the third element of his music business.

Handing over the business

Poor business practices and the Napoleonic wars led to Nägeli being unable to repay a loan. In turn, he had to hand over the management of his business to his creditor Jakob Christoph Hug, and its name was changed to ‘Nägeli & Compagnie’. Nägeli’s publishing house became his downfall.

He remained loyal to the company as an employee and had 10 years to buy back the business. Ultimately, he left it to Jakob Christoph Hug, with ‘Nägeli & Compagnie’ subsequently becoming ‘Musik Hug’.

A new company

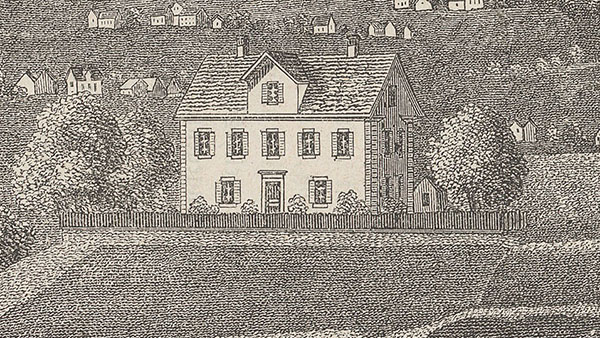

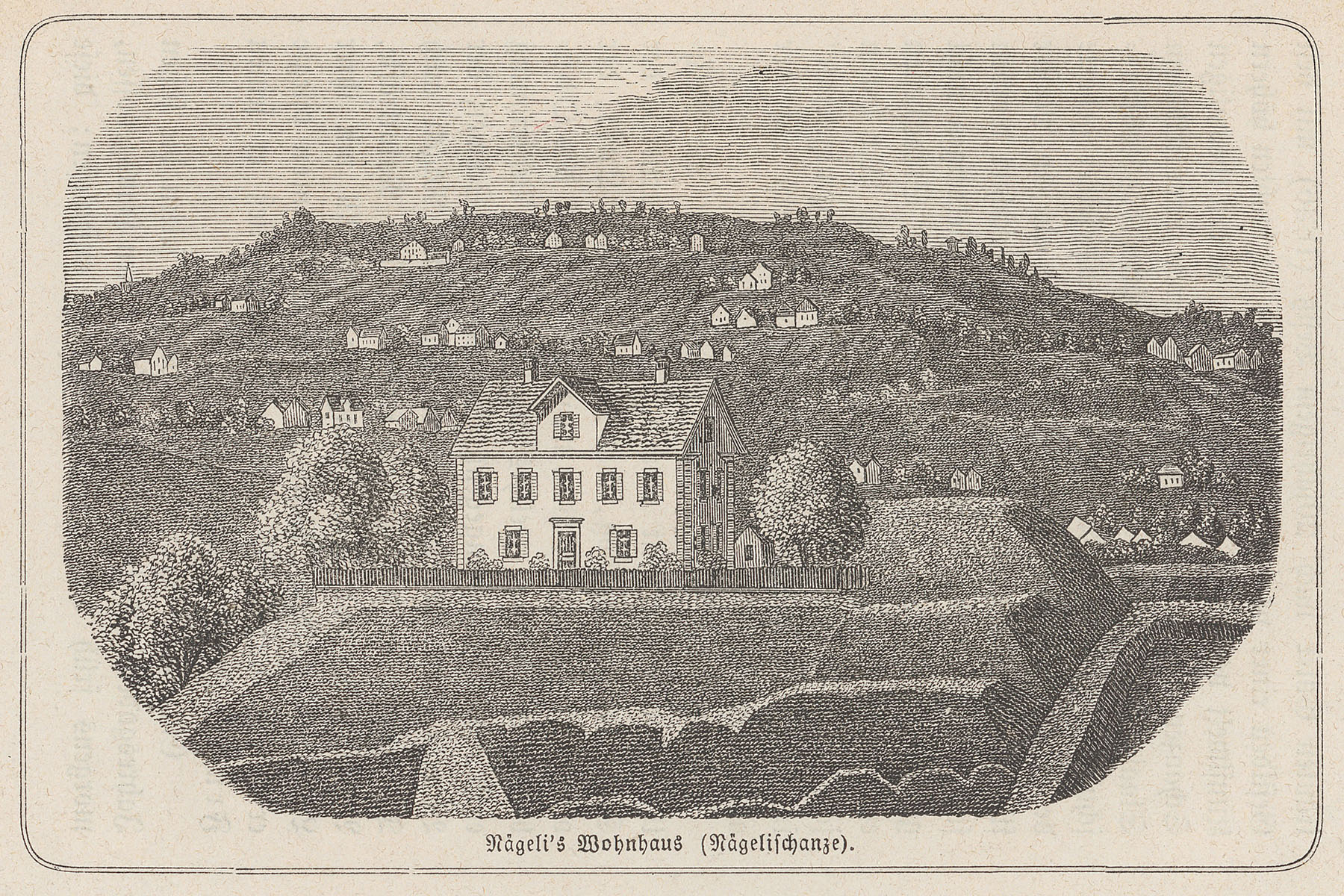

Eleven years after handing over the business, Nägeli founded a new, smaller company. Its business model was the same and the new shop’s premises were also in Zurich: in Nägeli’s home in the present-day university district. The newly founded music shop and library and associated publishing house were not lucrative ventures for Nägeli: the financial difficulties continued. However, he was able to retain ownership of this second company.

Death and estate

Nägeli died suddenly aged 63 from complications following a cold. His son, Hermann Nägeli, a pianist, continued his business and looked after his father’s estate, archiving business correspondence and ensuring that many sources detailing Hans Georg Nägeli’s life were preserved. The business was dissolved after Hermann Nägeli’s death in 1872 and the estate of the Nägeli company passed to the Cantonal Library of Zurich in 1875 (now Zentralbibliothek Zürich).

Selling and lending – the symbiotic relationship between different business models

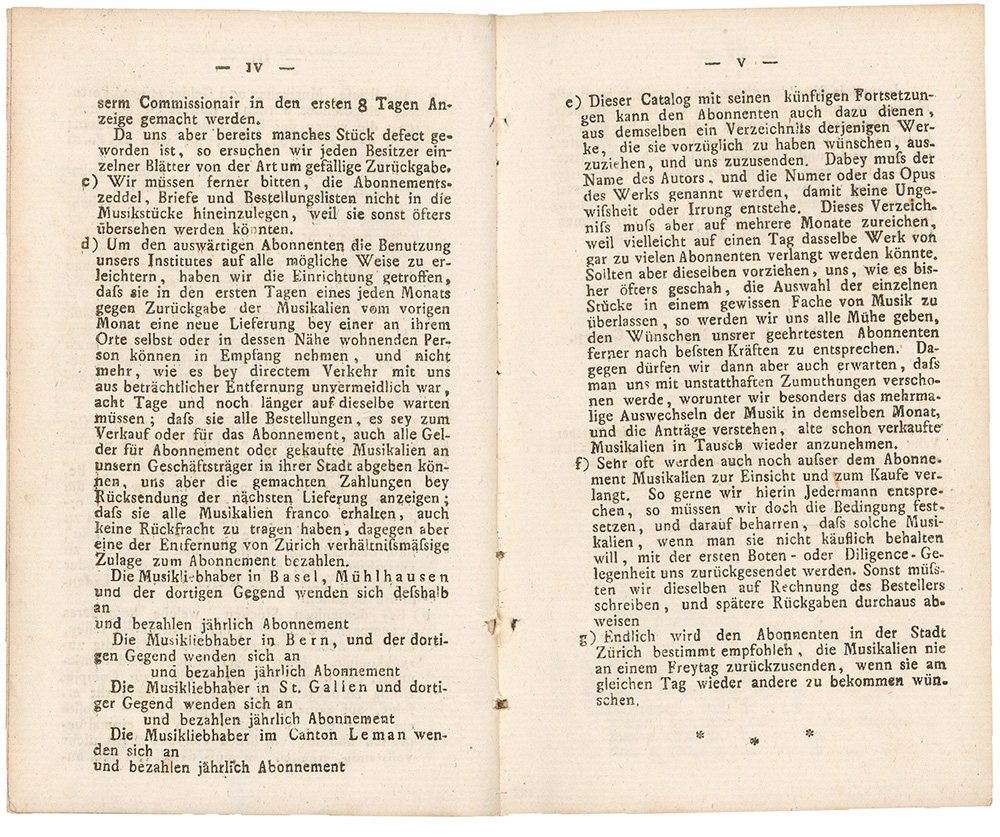

At the time of its establishment, Nägeli’s lending library for sheet music was a pioneering development in Switzerland and southern Germany. This enabled the Zurich-based entrepreneur to expand his clientele to neighbouring countries within just a few years. The lending library helped him find a foothold as a music retailer: subscribers were able to purchase the sheet music they had borrowed once their loan period had expired. This was particularly attractive to people with less money at their disposal, as renting the music enabled them to familiarise themselves with it and avoid making a purchase they would regret. Nägeli suggested to his customers outside Switzerland that they should set up music swap groups to save on (high) postage costs.

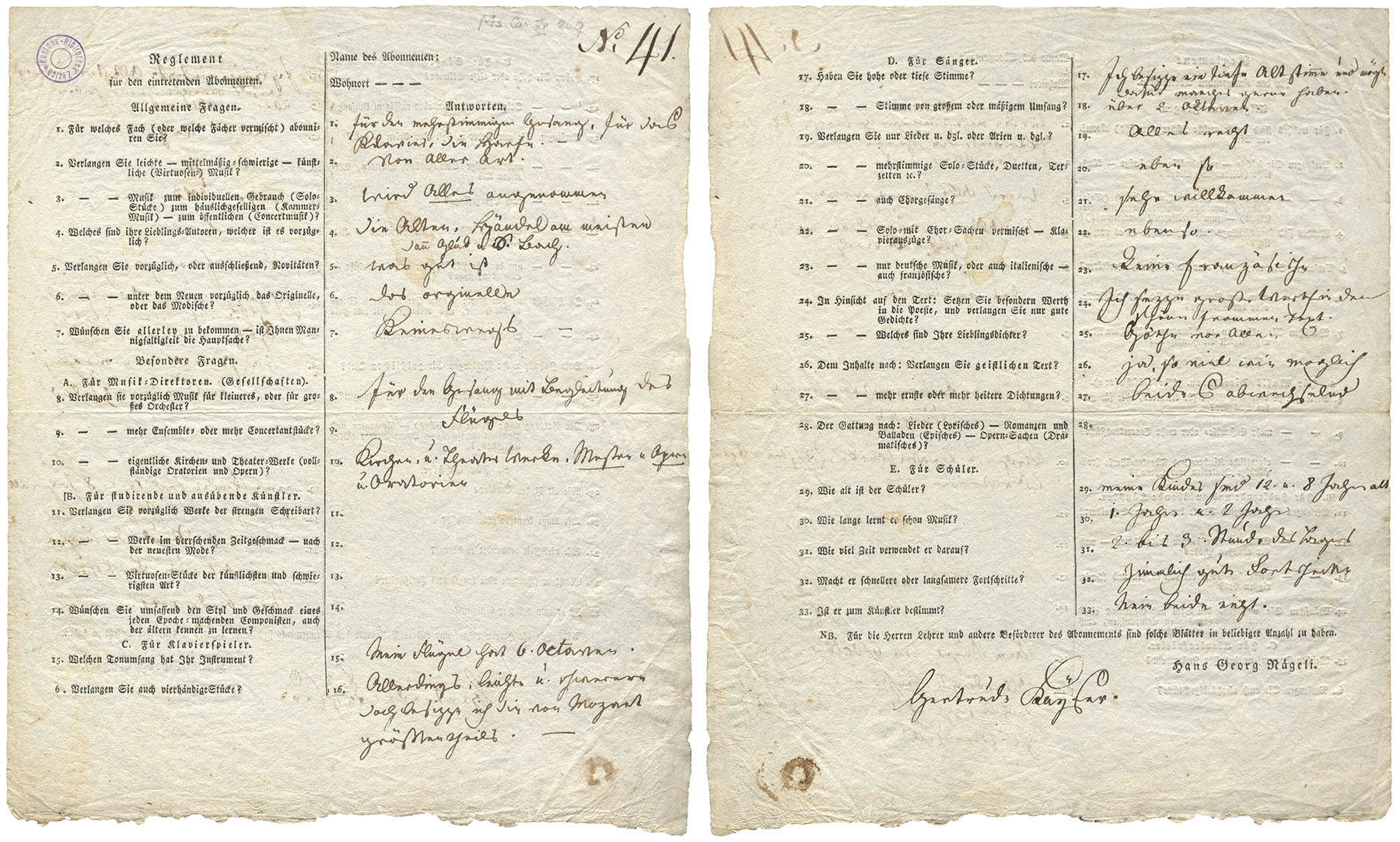

The ‘Regulation for incoming subscribers’ enabled subscribers to share information about their musical skills and interests with the lending library. This ‘Regulation’ – a questionnaire – served as a ‘market research tool in the modern sense’, as Tobias Widmaier puts it. The questionnaire pictured was likely submitted by Gertrud Kayser from Heidelberg, who wanted pieces ‘for voice with piano accompaniment’. She had clear requirements in terms of text: ‘I see great value in pleasant, happy text [...] Goethe, above all.’ She also provided details of the musical talents of her children, aged twelve and eight: they practised ‘two to three hours a day’ and were making ‘fairly good progress’. However, she had a clear response to the final question, as to whether they were ‘set to become artists’: ‘No, neither of them’.

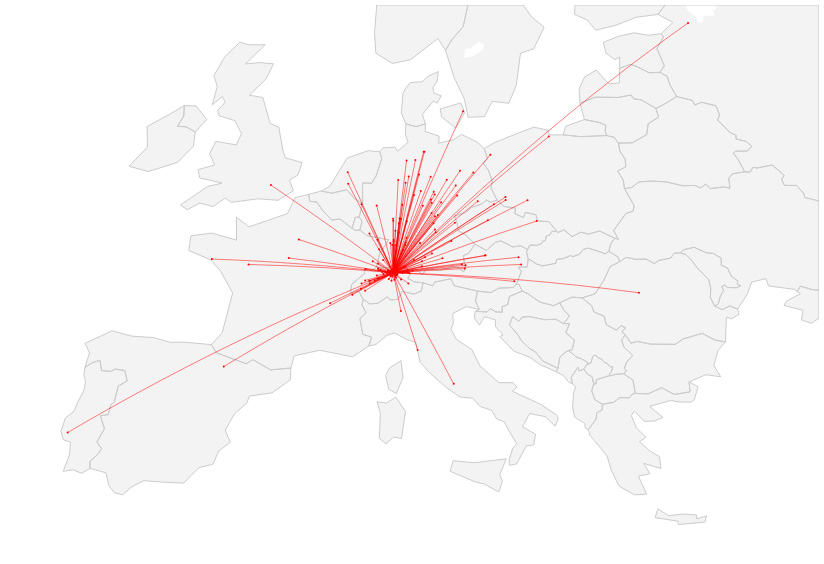

International supply chains

Nägeli’s work as a sheet music retailer and lender saw him quickly forge contacts on an international level. While he primarily supplied his wares to German-speaking countries, he bought his music from across Europe.

The Zurich-based businessman purchased mainly manuscripts from Italy, which he either published himself or sold to other publishers. Nägeli focused on the French market for sheet music in his first years of doing business and noticed that trends in Paris were far ahead of those of the German-speaking market. As a result, he strategically expanded his contacts in this region, as illustrated by a letter to the Institut National in Paris. In 1795, Nägeli reported that he was in correspondence with around 20 different Parisian music publishers. He used French music as capital across the entirety of the German-speaking territories, supplying it to certain prominent sheet music retailers such as Breitkopf in Leipzig and Artaria in Vienna. The Zurich-based entrepreneur’s interests did not always pay off, however: he had no success in establishing solid trading relations in England, despite various contacts there.

Nägeli as an educator and his singing institute

Music pedagogy was a further focus of Nägeli’s work. He saw education and, in particular, the school subject of singing, as an important means to promote a sense of community and religiosity among young people. In his view, making music was the most important form of school-based education. As a deeply religious person and son of a vicar, sacred music was particularly close to his heart. For Nägeli, coming together to sing religious texts represented finding unity in God.

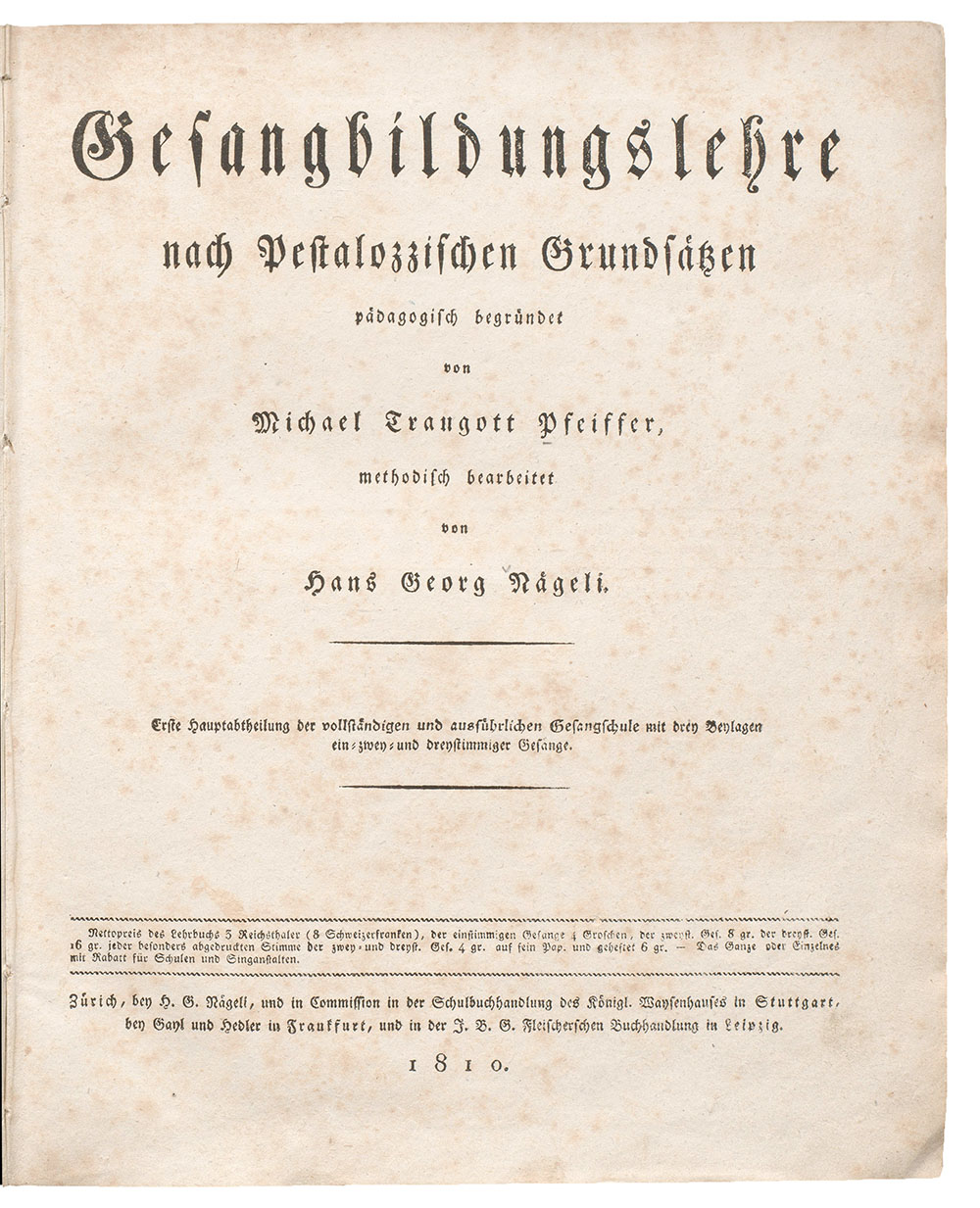

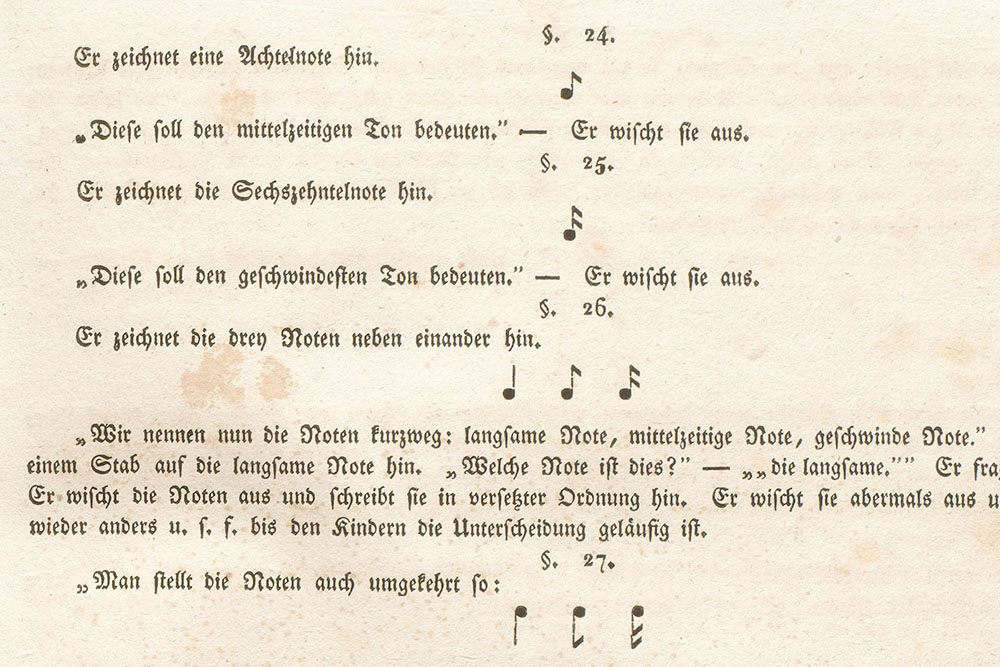

He created his ‘Vocal training guide following Pestalozzi’s principles’ in 1810, in collaboration with educator Michael Traugott Pfeiffer. This schoolbook included various songs and choral works, and well as methods demonstrating the need for music in education. Nägeli sold his ‘Vocal training guide’ in Switzerland and abroad, eagerly marketing it to school boards such as the Royal Bavarian Ministry of Public Education. In so doing, he attempted to establish his teaching and methods in schools throughout German-speaking Europe.

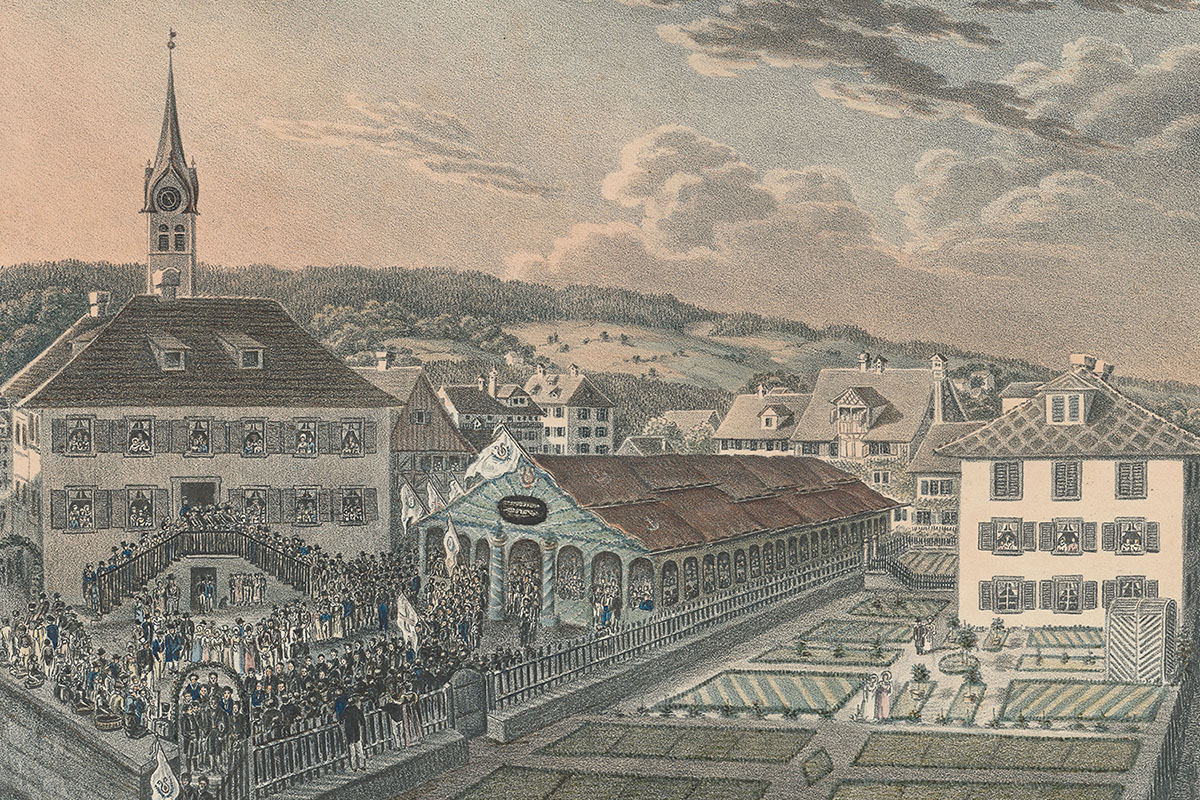

The establishment of Zurich’s Sing-Institut [Singing Institute] in 1805 occupied a special place among Nägeli’s endeavours. In a circular describing the opening of this choral school, Nägeli described his goal of encouraging choral music with a sacred focus as a method of education. No tuition was charged, which ensured it was accessible to all, although strict rules applied: punctuality and discipline were of critical importance.

A pioneer of sociability

The Sing-Institut [Singing Institute] was led by Hans Georg Nägeli as a director, composer and educator, and also reflected his ideal of social music-making. ‘Connecting people to one another’ and encouraging community, especially through music, were indispensable characteristics of what Nägeli saw as ‘real’ art. In fact, in his view, artists’ associations only existed to encourage socialising among people. He set out this perspective in a speech to open a meeting of the Schweizerische Musikgesellschaft [Swiss Music Society] in 1820. According to Nägeli, people enjoy making music together and engaging in ‘the most beautiful harmonies humanly possible’. Newly established singers’ associations in northern and southern Germany adopted Nägeli’s ideal of social music-making.

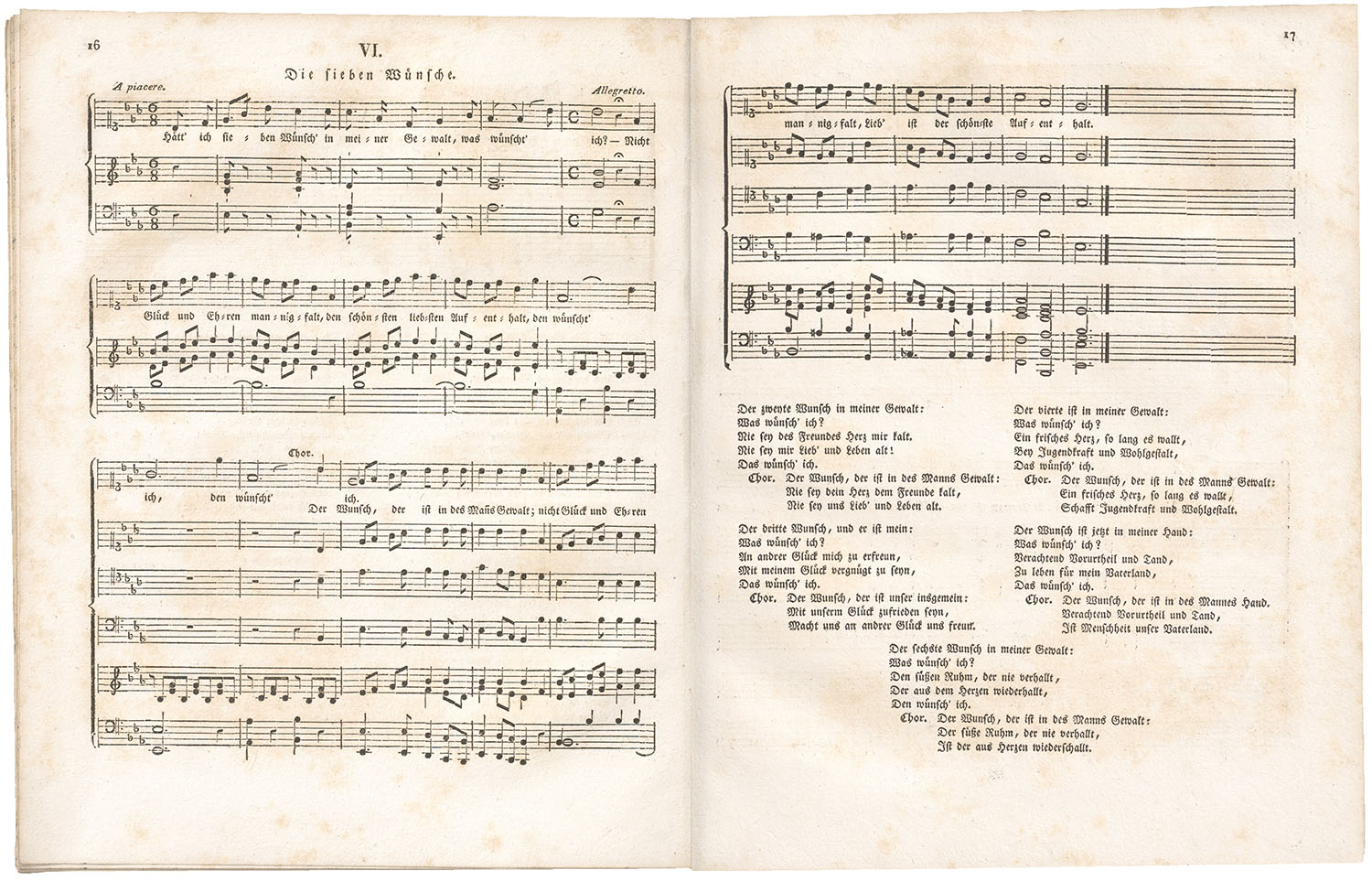

Hans Georg Nägeli composed a large number of songs for the Sing-Institut [Singing Institute]. The twelve volumes of ‘Teutonia’ are of particular interest, with their rounds and choral pieces to be sung ‘by the entire group of singers’. Social interaction and singing together are the primary focus, while perfect singing plays a subordinate role. The songs are kept simple so as many people as possible can join in, regardless of their age, gender, class or musical knowledge. Nägeli’s numerous compositions for male choirs were also very popular.

Alongside his work for the Sing-Institut [Singing Institute], Nägeli set up several choirs and was involved in the Allgemeine Musikgesellschaft Zürich [Zurich General Music Society], which he co-founded. In the very year it was established, he worked with State Chancellor Johann Rudolf Landolt to draw up a ‘Concert Ordinance’. This document reveals the objective of their concert programme: maximum diversity, with the programme alternating back and forth between vocal performances and purely instrumental music. The various genres of music and instruments ensured that all the members of the association could take part to best effect.

Nägeli’s broad impact shaped Zurich’s musical life, which brought him recognition time and again.

Well-informed and opinionated: Nägeli’s involvement in politics

Hans Georg Nägeli’s diverse range of endeavours led to him establishing a large, international network. He also used these contacts to learn about the political situation.

Nägeli’s interest in the new ‘Federal Treaty of the XXII Cantons’, paired with his sense of responsibility towards the Swiss Confederation, is reflected in a letter to Baron vom Stein. His 1814 speech on the ‘Project for a state constitution’ saw Nägeli express his views on various topics, including the role played by artists in politics:

«If artists create their free art for a free people, and do not simply want to provide entertainment for the great or the rich, but also want to contribute to the refinement of the life of society as a whole, they must speak with their full voice on all important matters that have a decisive impact on the life of society, [...] because, after all, it is also their [...] vocation to tie their impact to the state.»

He demonstrated similarly strong viewpoints during his time on Zurich’s council of education, to which he was elected at the age of 58. By this time, Nägeli’s pedagogical ideas and political views had matured and been tested in practice. He was unequivocally critical of other pedagogical writings, such as the draft school plan developed by teacher Ignaz Thomas Scherr. Nägeli complained of no fewer than twelve issues that ran counter to his ideal of education, including the following:

- Underestimation of the human organism

- Lack of clear understanding of the nature of education

- Ignorance regarding Pestalozzi’s approaches

- Poorly defined curriculum and materials

- Ignorance regarding interactions with the populace

Nägeli today – suggested reading

In recent years, Hans Georg Nägeli’s life has been researched in great depth. Authors explore the multi-faceted nature of his work as a music publisher, teacher and politician from various angles. The four most recent publications also offer an overview of his writings and musical works:

- ‘Hans Georg Nägeli (1773–1836). Einsichten in Leben und Werk’ [Hans Georg Nägeli (1773–1836). Insights into his life and work] by Martin Staehelin

- ‘Revolution und Geschichte. Hans Georg Nägeli und die demokratische Muse’ [Revolution and history. Hans Georg Nägeli and the democratic muse] by Louis Delpech

- ‘Hans Georg Nägeli. Komponist, Verleger, Musikmensch’ [Hans Georg Nägeli. Composer, publisher, musician] by Andrea Schmid

- ‘Autonome Kunst als gesellschaftliche Praxis. Hans Georg Nägelis Theorie der Musik’ [Autonomous art as social practice. Hans Georg Nägeli’s theory of music] by Miriam Roner

You can find more literature on Hans Georg Nägeli in the Zurich Bibliography. A website provides information on the activities undertaken by ZB Zürich to commemorate Nägeli’s 250th birthday and also includes selected resources.

This article was created by students working on a project run by Dr Hein Sauer and Professor Inga Mai Groote

at the Institute of Musicology of the University of Zurich.

It supplements the exhibition of the same name in the music department of Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Authors: Nikolaj Bauer, Viviane Bettschart, Lea Fussenegger, Daria Haidashevska, Julia Hasler,

Lucie Jeanneret, Milo Krynski, Elia Pianaro, Sandra Sanchez, Anna Serra, Amalia Vasella

July 2023

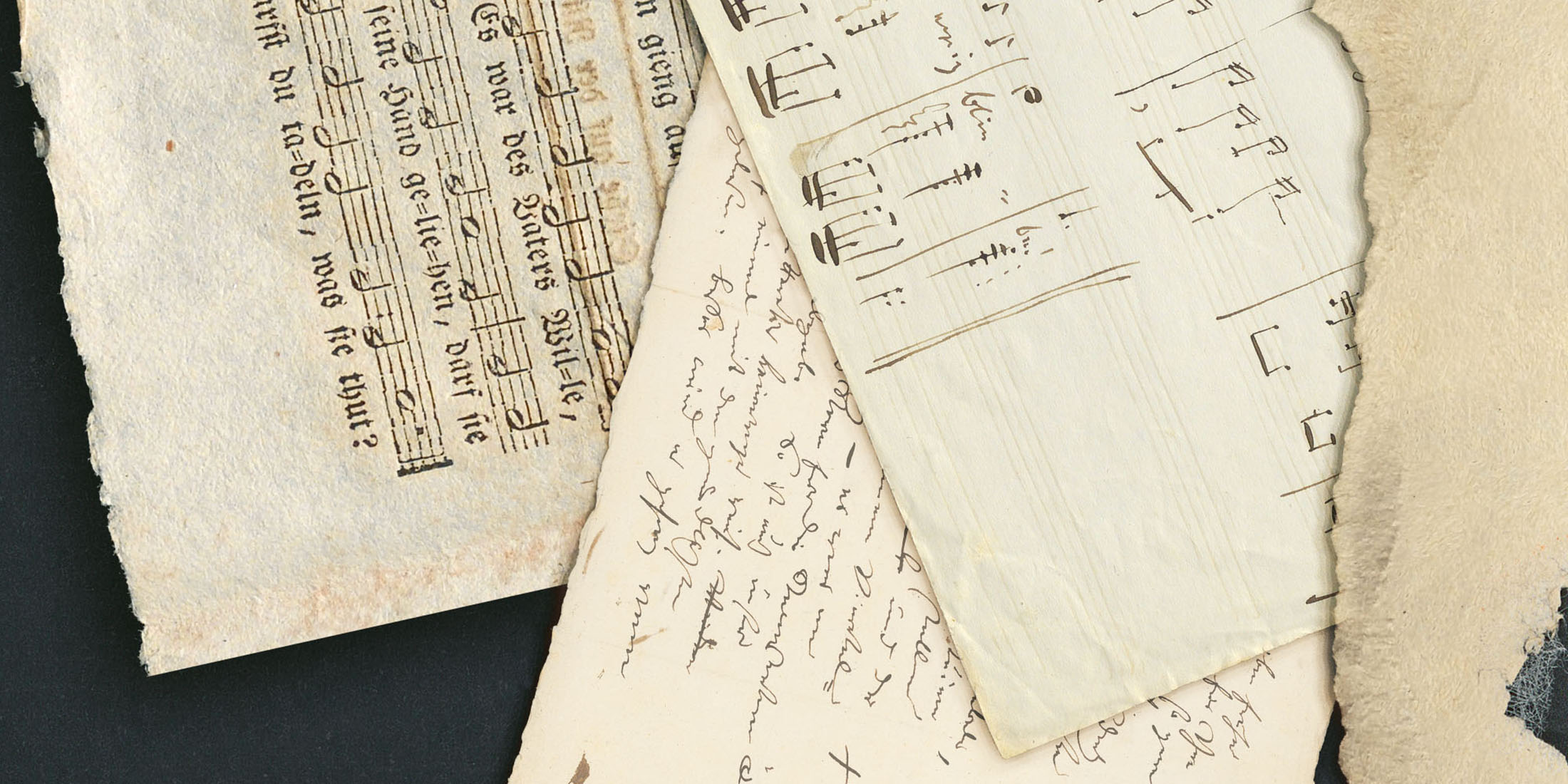

Header image: Pages from the estate of Hans Georg Nägeli held at Zentralbibliothek Zürich. (Benedikt Merkle)

![A concert programme for the Allgemeine Musikgesellschaft Zürich [Zurich General Music Society] dated 1839, displaying different styles, instruments and genres. (Image: ZB Zürich)](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/zuerich/N%C3%A4geli/20230706-TUR-Zuerich-HansGeorgNaegeli-10.jpg)

![The Nägeli memorial on the Hohe Promenade, between 1875 and 1889. The memorial was erected by the Schweizerische Sängerverein [Swiss Singers’ Association] to commemorate Nägeli’s services to the culture of singing. It has been moved several times and is now located behind the Kantonsschule Hohe Promenade. (Image: Heinrich Siegfried/ZB Zürich)](https://www.zb.uzh.ch/storage/app/media/zuerich/N%C3%A4geli/20230706-TUR-Zuerich-HansGeorgNaegeli-12.jpg)