Reformation

Some 500 years ago, on 1 January 1519, Huldrych Zwingli (1484–1531) took up his post as a lay priest at the Grossmünster in Zurich and ushered in the Reformation in Switzerland. Here we present an overview of the key issues and some highlights related to the Reformation from our collections.

When Zurich made world history

On the eve of the Reformation

In Zwingli’s day Zurich had a population of around 5,000 – considerably smaller than Strasbourg’s 20,000, and dwarfed by Venice’s 150,000. The city had no significant trading links. Many of its inhabitants were craftspeople. The textile and silk industry did not really take off until the arrival of Protestants seeking refuge from religious persecution. Poor harvests could have a severe impact on the populace, making it difficult for people to feed themselves properly, as described in the diaries of Thomas Platter, who attended the Fraumünster school in 1523. Life expectancies generally were much lower: in the 16th century Zurich was repeatedly beset by the plague, which claimed numerous victims.

Disputes over mercenaries

In Germany the Reformation was sparked by indulgences, but in Switzerland differences over the issue of the mercenary system repeatedly pitted opposing sides against each other once the Reformation began. For the rural, Catholic cantons, the mercenary system was an important source of income. Most Protestant areas, meanwhile, agreed with Zwingli in regarding it as a cynical exercise in profiteering at the expense of numerous innocent young men.

Breakthrough of the Reformation

While Martin Luther’s Reformation in Wittenberg enjoyed princely patronage, with Elector Frederick the Wise supporting his subject and endorsing his actions, Zurich’s Reformation was conducted through the offices of the city. It was not until four years after Zwingli had begun preaching that, on 29 January 1523, the Council approved the introduction of the Reformation to Zurich. This had a far-reaching impact not just on the Catholic Church but also on many areas of private and public life. The dissolution of the monasteries freed up large amounts of capital that could be used for poor relief, education and health care. The new faith also reduced the burden on individuals, as money no longer needed to be spent on rituals, indulgences and so on but could be invested elsewhere.

Martin Luther

The German reformer’s moment of illumination (the “tower experience”) probably came about prior to 1515 in his study in the south tower of St. Augustine’s Monastery in Wittenberg. It was not until several years later, in 1517–18, that Zwingli took note of him. He always maintained that he had come to the same conclusions independently of Luther. As a lay priest in Zurich, Zwingli encouraged people to read Luther and, to this end, imported hundreds of his writings from Basel. Unfortunately the two reformers were unable to agree on the concept of the Eucharist, which had regrettable consequences for the history of the Reformation and Protestantism.

Erasmus of Rotterdam

In his “Amicable Disputation with Luther” of February 1527, Zwingli recalled: “For I, from myself, bear witness before God that I have learnt the power and essence of the Gospels from reading the writings of John and Augustine, and in particular from the close study of the Greek Epistles of Paul, which I transcribed by my own hand eleven years ago.” That transcription was based on the Greek New Testament published by Erasmus of Rotterdam in 1516. Indeed, more broadly, Erasmus’s writings – often couched in terms critical of the Church – made a major contribution to Zwingli’s career as a reformer.

The printed book: the first mass medium

A key factor in the spread of the Reformation was book printing, which allowed texts to be disseminated swiftly and widely. Zwingli convinced Christoph Froschauer, the city’s most important book printer of the time, to support his cause. Over a period of decades Froschauer printed thousands of Bibles, Bible sections and Reformationist tracts that were disseminated around Europe.

Books published by Christoph Froschauer can be found in our collection.

Radical hotheads

Not everyone in Zurich was in agreement with Zwingli. Apart from the citizens and clerics faithful to Rome who ultimately left the city, a group of mostly younger fellow campaigners of Zwingli’s set themselves up in opposition to him. Conrad Grebel and Felix Manz, in particular, accused Zwingli of introducing the Reformation too tentatively and compromising with the Council. The situation escalated to the point that, in 1527, the Council even pronounced death sentences against them. Since they taught adult baptism, they later came to be known as “rebaptisers”. Today’s Amish and Mennonites are descended directly from this Zurich group of Baptists, whose spirit lives on in numerous free churches.

The Battle of Kappel

By 1525, Zwingli was already planning attacks on the Catholic areas, in the belief that the Gospels could not be preached there until they had been conquered. While the First War of Kappel in June 1529 was settled amicably with the Kappel milk soup, the Second War of Kappel in October 1531 ended in a bloody battle that brought defeat to the Protestants and the death of Zwingli.

Zwingli’s personal library

No diary by Zwingli has survived, but 205 titles from his personal library have, almost all of which are in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich. The reformer’s annotations to his books offer a fascinating insight into the development of his theology and his private life. They are available in digital form on the e-rara.ch platform (except where it was impossible to digitise them for conservation reasons).

Events marking 500 years of the Zurich Reformation

A number of institutions are organising exhibitions, events and films to commemorate this turbulent and important period in Zurich’s history. More information is available at the following links:

- www.refo500.ch

- www.zh-reformation.ch

- www.zhref.ch

- www.zwingli.ch

- “500 Jahre Reformation – Wie die Schweiz gespalten wurde”, documentary by Andreas Kohli in the SRF DOK series.

Five highlights from our collections

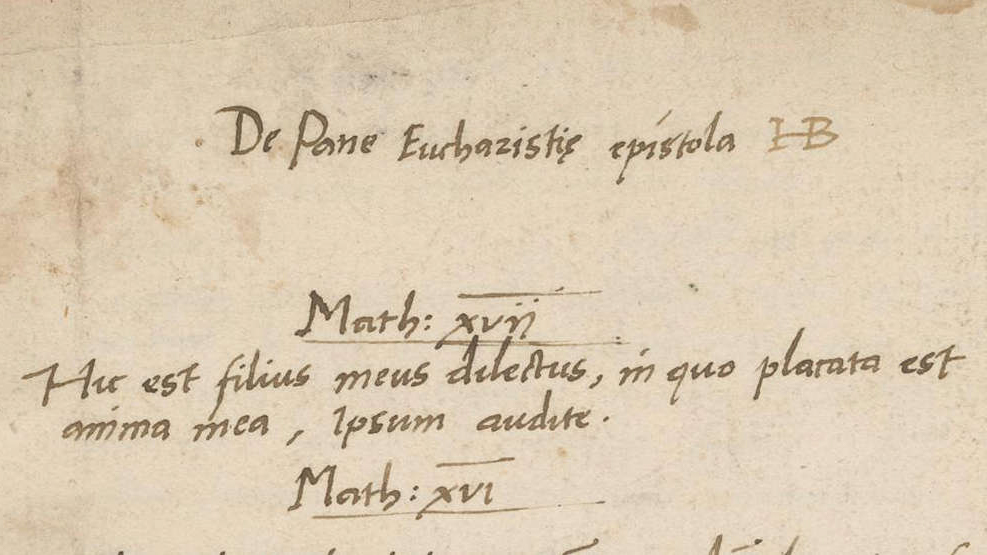

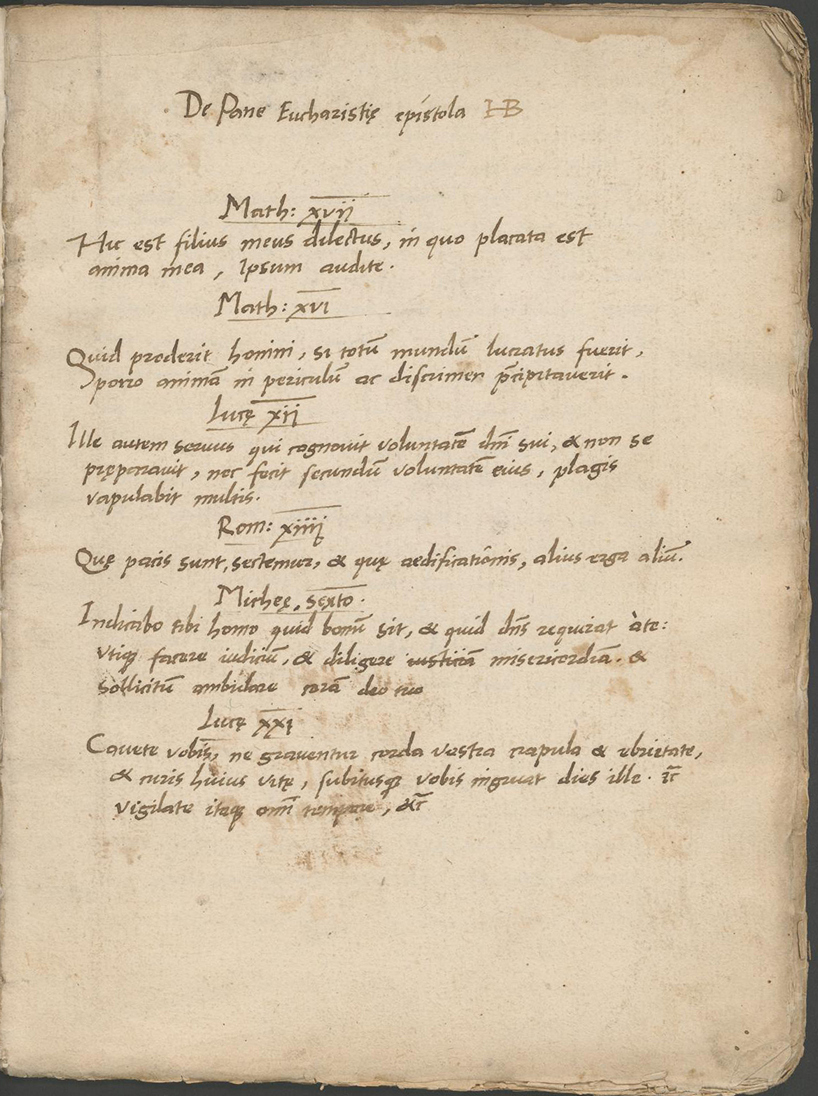

1. Zwingli’s transcription, in his own hand, of the Epistles of Paul based on the Greek New Testament by Erasmus of Rotterdam, which was printed in Basel in 1516.

ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: RP 15

2. Portrait of Huldrych Zwingli painted by Hans Asper of Zurich in 1549.

ZB, Department of Prints and Drawings and Photo Archive, call number: Inv. 6

3. Map of the Holy Land included in the German-language Froschauer Bible of 1525. It was the first printed map to feature in an edition of the Bible.

ZB, Map Department, call number: 3 Nv 02: 1

4. Martin Seger: Dyβ hand zwen schwytzer puren gmacht …, Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1521. The title woodcut was designed with Zwingli’s involvement. It shows the so-called “Godly Mill”. Jesus Christ is depicted “pouring” the Apostles and Evangelists in, while “godly” flour emerges at the bottom, which Erasmus of Rotterdam is putting into sacks and “baking” Bibles with Luther.

ZB, Rare Book Department, call number: Zwingli 106 a.1

5. Bible, Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1531. The translation of the Zurich Bible from Hebrew (OT) and Greek (NT) was completed five years before Luther’s. It was published as a single volume in 1530 and as a luxury Bible in folio format in 1531.

Reformation timeline

Zwingli comes to Zurich

Ulrich Zwingli is appointed lay priest at the Grossmünster in Zurich. He preaches for the first time on 1 January. He calls for reform of all aspects of life and for improvements not just within the Church but in all people.

※※※※※

A plague epidemic breaks out in the city. Zwingli falls sick with the plague in September, but survives. He sees the hand of God at work in his recovery. It is an experience that will shape his theological interpretation of the world.

Huldrych Zwingli is appointed to the Grossmünster in 1519.

Source: coloured pen drawing in a copy of Heinrich Bullinger’s History of the Reformation, 1605, ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: Ms B 316, f. 15r

Opposition to the mercenary system

Zwingli’s sermon opposing the mercenary system. Zurich’s Council forbids the recruitment of “Reisläufer” – mercenaries – on Zurich territory. The other members of the Confederacy react with outrage.

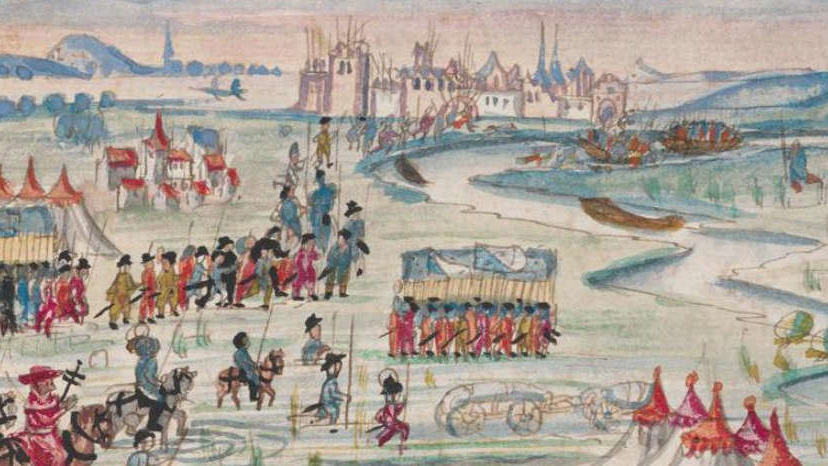

Mercenaries from Zurich on the way to Milan with the Cardinal of Sion in 1521 pass through marshy land.

Source: coloured pen drawing in a copy of Heinrich Bullinger’s History of the Reformation, 1605, ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: Ms B 316, f. 49r

The sausage controversy

At a convivial meal the book printer Christoph Froschauer, a good friend of Zwingli’s, breaks the rules on fasting by serving up sausages for himself and his invited guests. Zwingli is present, but does not partake.

The Council of Zurich condemns the breach of fast and orders an investigation. Zwingli, however, defends Froschauer’s actions in a sermon and with the tract “Vom Erkiesen und Fryheit der Spysen”, which he has printed by Froschauer. This brings Zwingli into conflict with the Bishop of Konstanz.

First printer’s mark of the Froschauer printing works, 1521, ZB Department of Prints and Drawings, call number: Varia Druckersignete I, 7

The First and Second Zurich Disputations

The First Zurich Disputation, attended by some 600 spiritual and temporal representatives, takes place on 29 January. Zwingli’s arguments against the fasting rules, supported by reference to the Scriptures, win the day and the Council abolishes the rules.

An extract about the First and Second Zurich Disputations on YouTube.

※※※※※

Following a second Disputation at the end of October the Council of Zurich declares the teachings and instructions of Zwingli to be binding on all of Zurich’s spiritual community. The removal of religious images from Zurich’s churches is ordered, to be completed within half a year. Thus Zurich’s Council takes political responsibility for the conduct of the Reformation.

※※※※※

Owing to theological differences, the Baptists increasingly distance themselves from Zwingli’s Reform movement.

Disputation at the town hall in Zurich in January 1523.

Source: coloured pen drawing in a copy of Heinrich Bullinger’s History of the Reformation, 1605, ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: Ms B 316, f. 75v

Persecution of the Baptists and “Christliches Burgrecht”

The Zurich Council views the Baptist movement increasingly as a political threat, and steps up its persecution. Baptist leader Felix Manz is sentenced to death for perjury and disobeying the edicts of the magisterial authorities, and is drowned in the River Limmat on 5 January.

※※※※※

Zurich concludes a mutual defence agreement with the Reformed Imperial City of Konstanz. Known as the “Christliches Burgrecht”, it guarantees that each will come to the other’s aid in the event of attacks on their faith. Similar alliances with other Reformed cantons are added in the years that follow.

The Baptist Felix Manz being drowned in the Limmat on 5 January 1527.

Source: coloured pen drawing in a copy of Heinrich Bullinger’s History of the Reformation, 1605, ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: Ms B 316, f. 284v

The First War of Kappel and the Marburg Colloquies

The Catholic cantons band together in a “Christian Union” against the Reformed cantons.

Disputes between the alliances of Catholic and Reformed cantons lead to the First War of Kappel. This ends peacefully and inconclusively with the famous “Kappel milk soup” and the First Peace of Kappel.

※※※※※

In October the Marburg Colloquies, the most important gathering of theologians in the first Reformation period, take place. Ulrich Zwingli, Martin Luther, Philip Melanchton and Johannes Oeklampad discuss the Biblical foundations of the Eucharist. Zwingli and Luther cannot agree, leading to a confessional rift and the emergence of two separate Reformed churches.

In June 1529, on the border between Zug and Zurich, soldiers from both sides eat a soup made of milk and bread from the same cauldron.

Source: coloured pen drawing in a copy of Heinrich Bullinger’s History of the Reformation, 1605, ZB, Manuscript Department, call number: Ms B 316, f. 418v

The Zurich Bible and the Second War of Kappel

The book printer Froschauer publishes the first complete German translation of the Old and New Testaments, later known as the “Zurich Bible”.

※※※※※

Disputes between the Reformed and Catholic regions of the Old Confederacy lead to the Second War of Kappel. On 11 October, Zwingli is killed in battle near Kappel. Zurich suffers a defeat. The Second Peace of Kappel is signed by both sides on 20 November. It brings an end to the spread of the Reformation in German-speaking Switzerland, with some places being forced to reconvert to Catholicism.

※※※※※

On 9 December, Heinrich Bullinger is appointed Zwingli’s successor as head of the Zurich church.

Heinrich Bullinger, painting by Hans Asper, 1559, ZB, Department of Prints and Drawings, call number: Inv 8

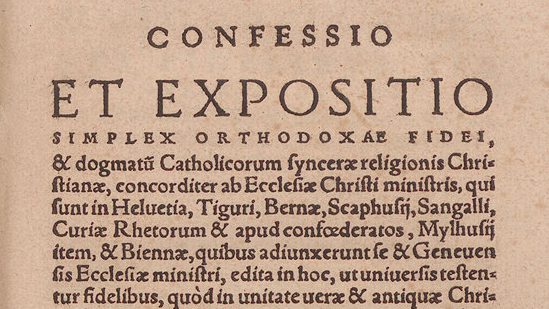

The First Helvetic Confession

Together with Bern, Basel, Schaffhausen, St. Gallen and Mühlhausen, Zurich issues the “First Helvetic Confession”. It is regarded as the first joint confession of faith by the Reformed German-speaking cantons.

A digitised version of the First Helvetic Confession can be found in a collection of Bullinger’s writings at e-manuscripta.ch.

The First Helvetic Confession, 1536

Unity in the Reformed Church

The advance of the Counter-Reformation and the hostility of the Lutherans lead to a discussion within the Reformed churches and the drafting of the “Consensus Tigurinus”. In its 26 articles, Heinrich Bullinger, John Calvin and Guillaume Farel resolve the differences of faith between Zwinglians and Calvinists. The document is signed in Zurich in May.

Iohannes Calvinus der H. Schrifft Lehrer, coloured woodcut, after 1564, ZB Department of Prints and Drawings, call number: Calvin, Joh. I, 38 (3)

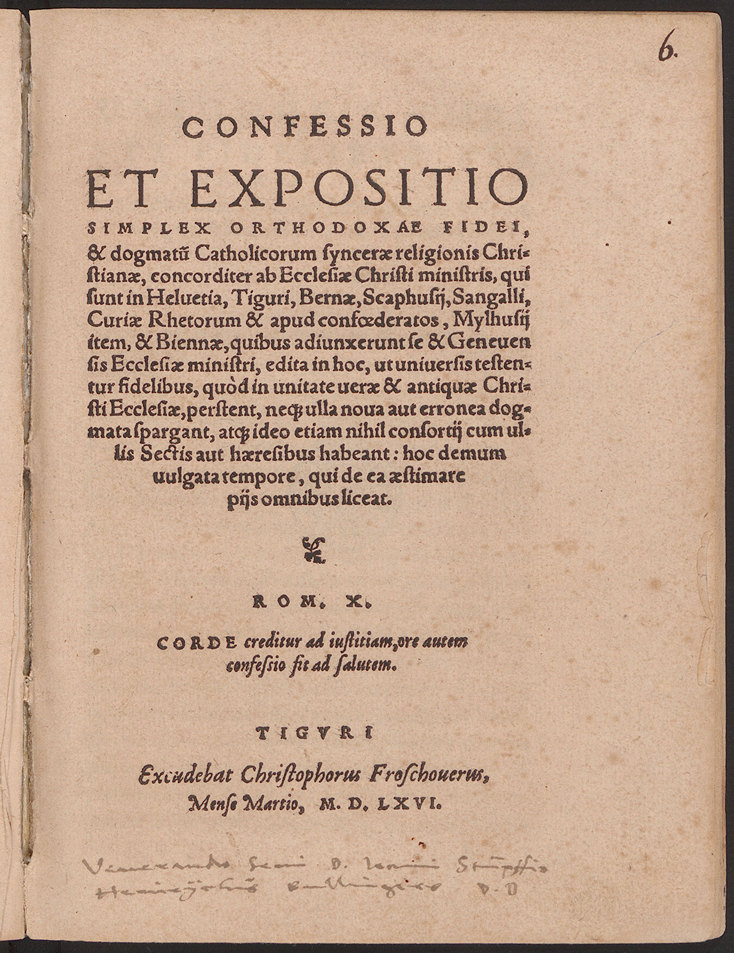

Bullinger’s spiritual testament

In 1561 Heinrich Bullinger writes the “Second Helvetic Confession”. In 1564 he falls ill with the plague and hands the document to the Zurich Council as a spiritual testament. The Second Helvetic Confession is adopted by all the Reformed churches of German-speaking Switzerland (except Basel), as well as by Geneva and other countries, in 1566.

You can find the “Second Helvetic Confession” among our holdings.

The Second Helvetic Confession, 1566

The Zurich Reformation in the press

If you would like to know what newspapers and periodicals had to say about the Zurich Reformation, consult the Zurich Bibliography.

Literature about the Zurich Reformation

Literature about the Zurich Reformation held by the Zentralbibliothek can be found in the Rechercheportal.