Wollishofen joins the city – an involuntary incorporation

Mergers between communes – the basic unit of local government in Switzerland – are a frequent occurrence: in the canton of Zurich alone, the total number has fallen over recent years from 171 to 162. But the biggest instances of communes being incorporated into the cities occurred some time ago: 1893 and 1934 in Zurich, 1922 in Winterthur. Wollishofen has been part of the city of Zurich since 1893. The union was far from painless.

Wollishofen – village, commune, community

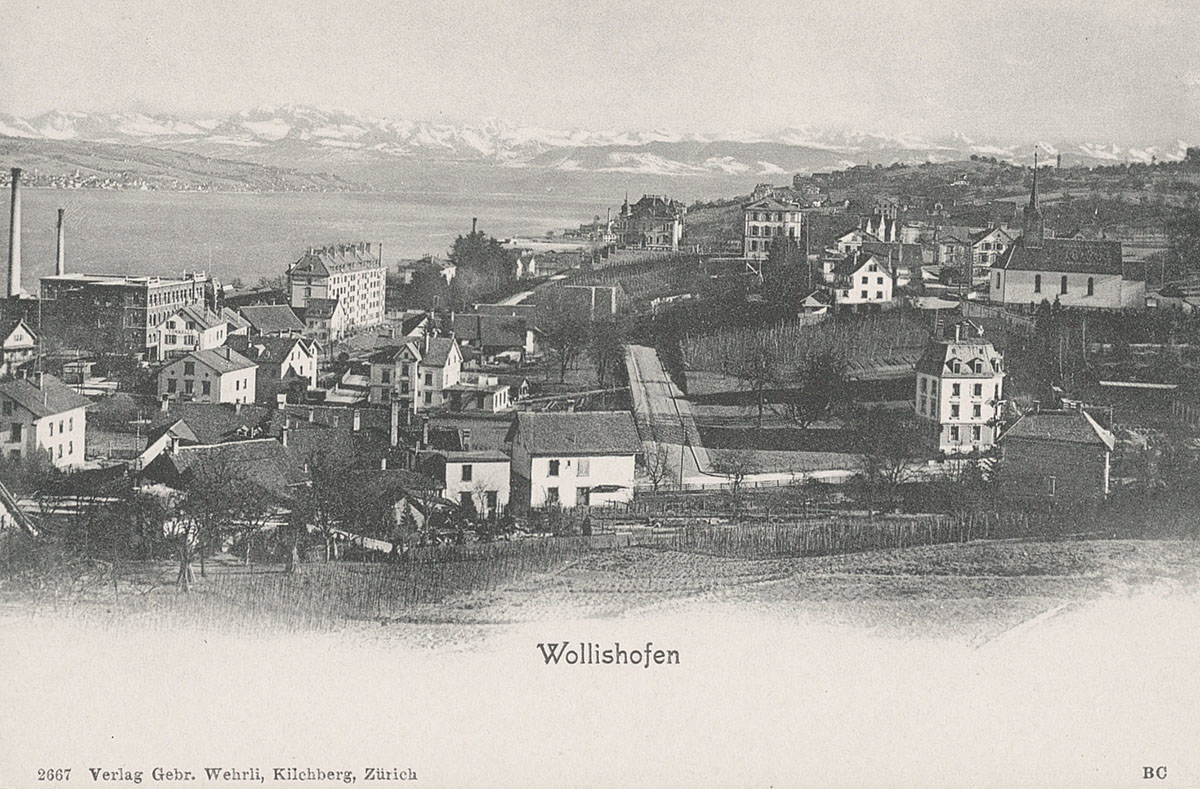

Wollishofen did not become an independent commune until 1803. Prior to that, the village, along with Enge, formed the greater bailiwick of Wollishofen. The village itself consisted of the three districts of Honrain, Wollishofen and Erdbrust.

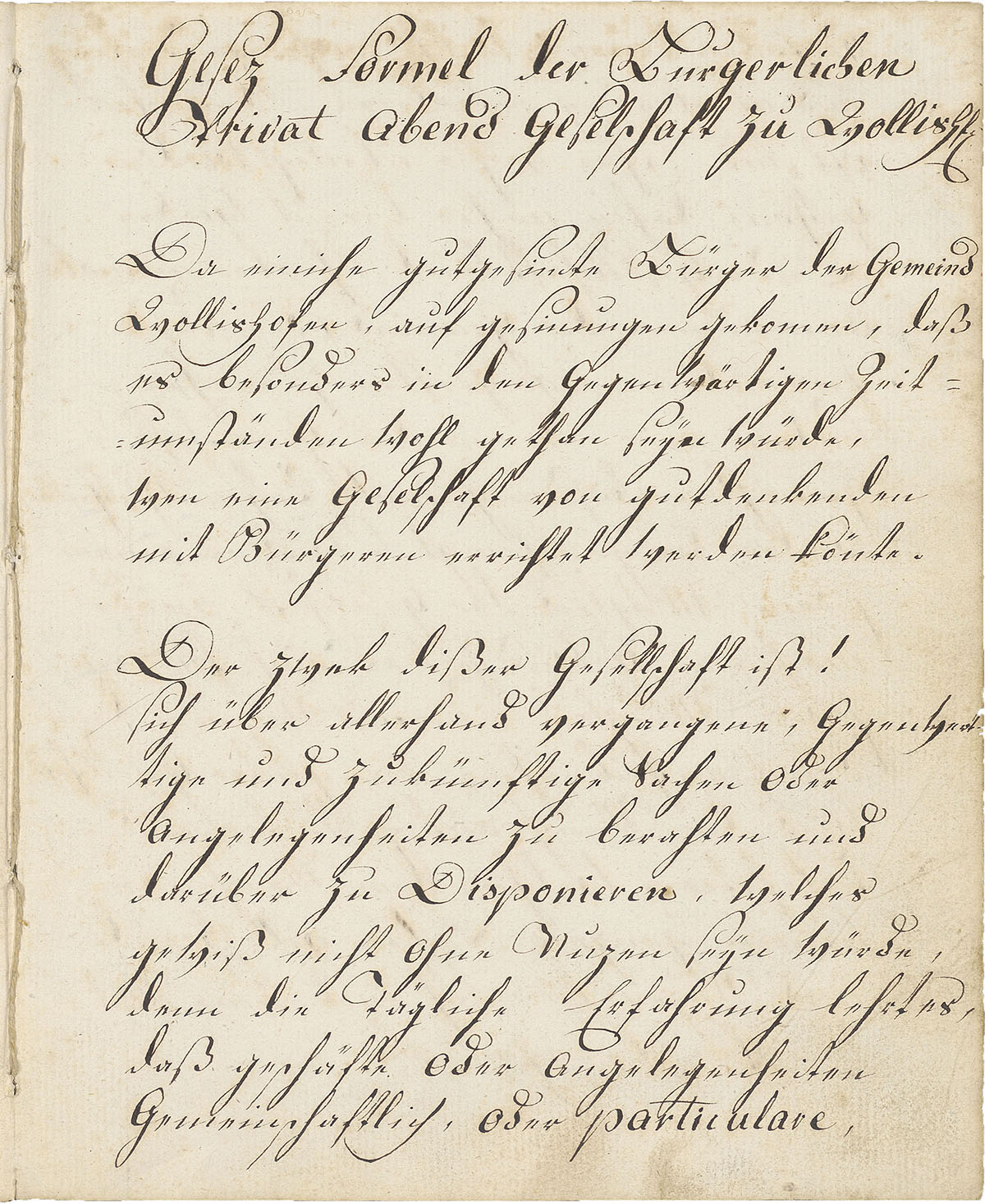

The sources soon reveal a nascent Wollishofen identity, but it only really came into its own following the end of the Ancien Régime when, in 1798 – the year of the Helvetic Revolution – a citizens’ evening society was founded. It brought together the village elite, but also provided a home for dedicated Wollishofers. It continues to this day as a reading society.

Aussersihl wants to be part of the city

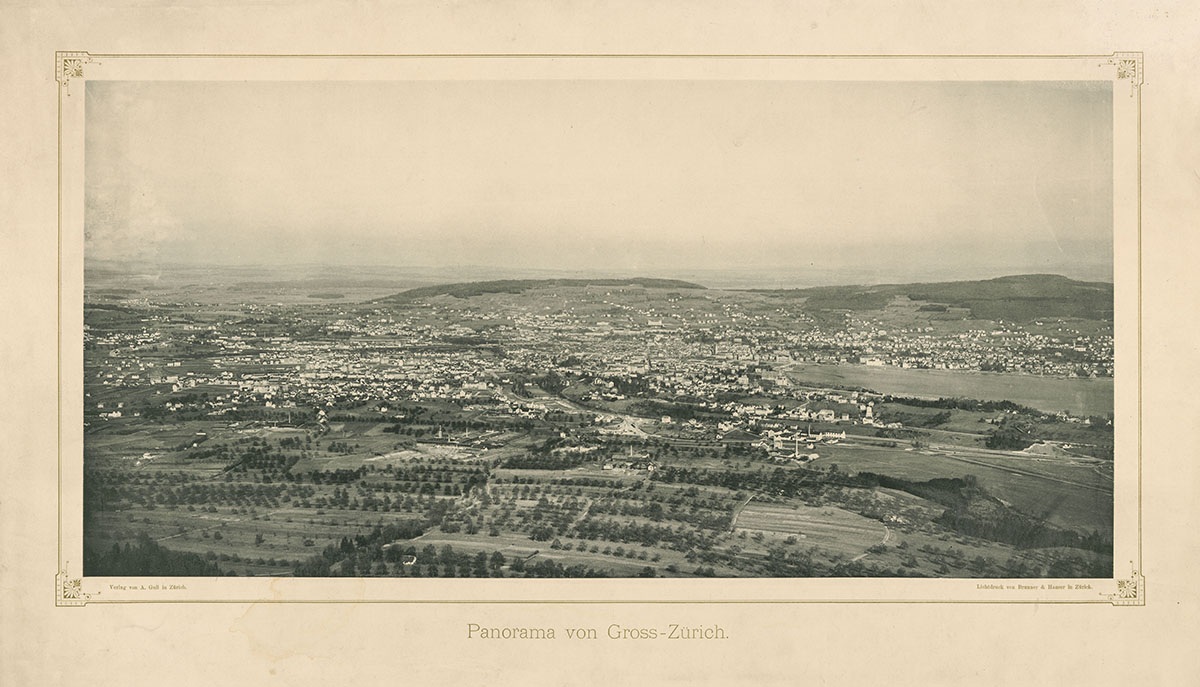

The population of the city of Zurich and its surrounding communes grew sharply in the 19th century, in most cases due to immigration by families from elsewhere. This changed the relationship between the city and the communes.

The industrial commune of Aussersihl was particularly keen to be incorporated into the city. In 1861 its communal president submitted a petition to that effect to the City Council of Zurich. It was rejected and there was no immediate follow-up. However, a second motion to the Cantonal Council in 1885 gave rise to a substantial political movement.

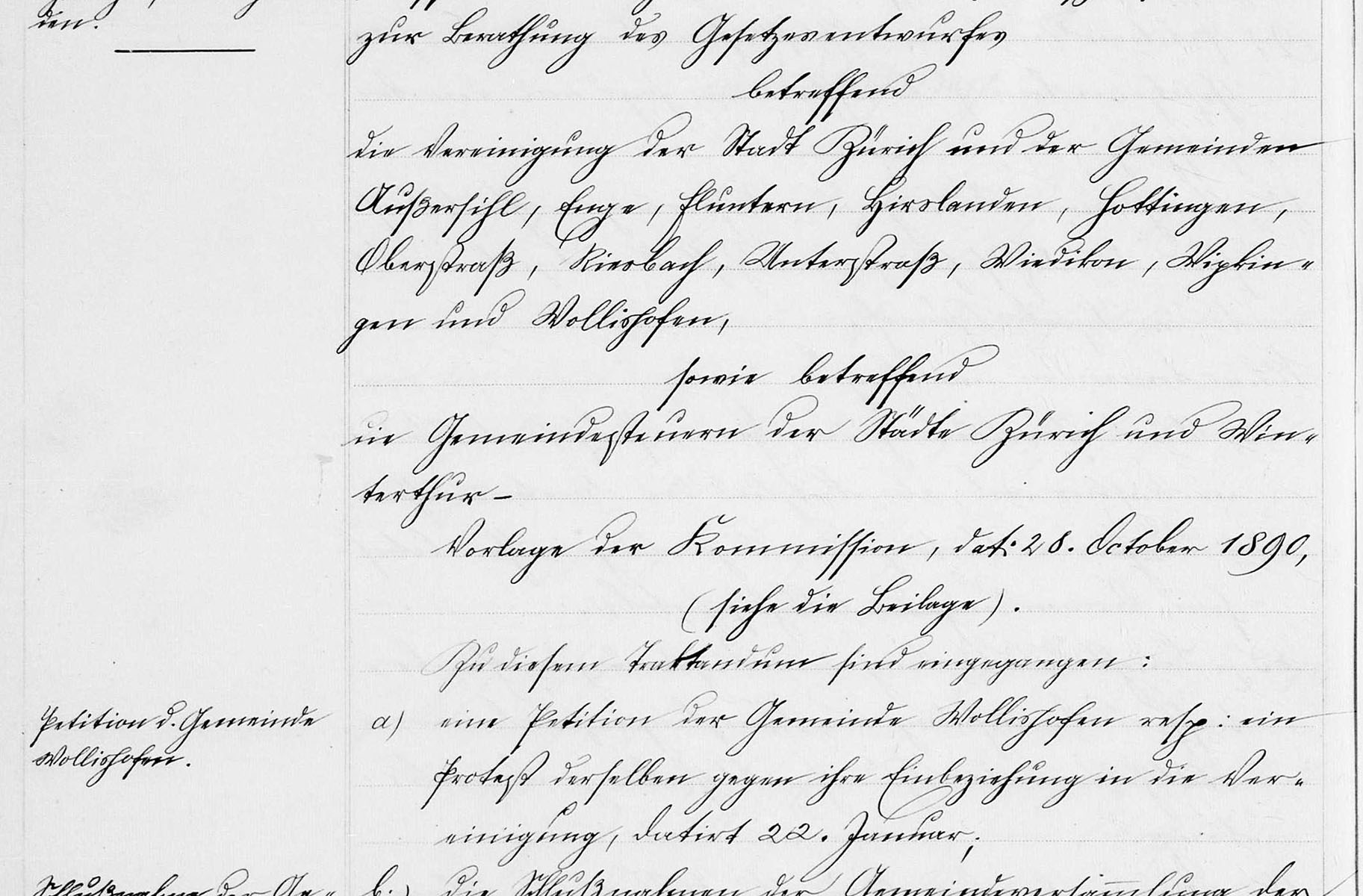

A preparatory committee then drew up an application to incorporate a further ten communes along with Aussersihl. Despite an official protest by Wollishofen, the Cantonal Council adopted the «Law concerning the incorporation of the communes of Aussersihl, Enge, Fluntern, Hirslanden, Hottingen, Oberstrass, Riesbach, Unterstrass, Wiedikon, Wipkingen and Wollishofen into the City of Zurich» in 1891.

Wollishofen fights to retain its independence

The referendum campaign stirred powerful emotions. Those in favour invoked solidarity and a common destiny; those against deployed the arguments of federalism and venerable tradition. On 9 August 1891, the law was approved, with 37,843 voting in favour and 24,904 against. Only Wollishofen and Enge – the latter by a very small margin – rejected the proposal, but there was also strong opposition in Zurich, Fluntern, Hottingen and Riesbach.

After a heated session of the communal assembly, Wollishofen lodged an appeal against the result, arguing that incorporation against the wishes of the commune concerned was unconstitutional. The Federal Supreme Court dismissed the appeal, essentially on the grounds that Zurich’s Constitution of 1869 did not offer a guarantee to the communes.

Why did Wollishofen oppose the proposal?

To this day, opinions differ as to why Wollishofen took an active part in the preparatory committee, but came out heavily against the move in the cantonal vote. One important aspect that sheds some light on the result is that there were no consultative votes before the final vote at cantonal level. That in itself, however, is not enough to explain Wollishofen’s rejection.

The Historical Lexicon of Switzerland refers only to the commune’s wealth. A more important factor is likely to have been that Wollishofen was still a largely rural community and had developed a strong sense of identity. In any event, the members of the Wollishofen Guild, which was founded after the incorporation, had to pledge «to preserve the particular character of their village as far as possible against the rapidly expanding city». That passage was later removed from the articles of association.

A cultural rapprochement

The disappearance of the guild’s traditionalist pledge is an indication that, as time passed, the people of Wollishofen came to terms with their incorporation. A number of factors contributed to this, such as the early extension of the tram route beyond Enge to Wollishofen.

The politician and historian Conrad Escher (1833–1919) also made an interesting observation, putting forward in his 1906 work «Rückblick in die Vergangenheit» the idea that relocating the orphanage to Wollishofen would «attach it more to the city and invigorate in its inhabitants the sense of belonging to our community». He thus viewed the transfer of the venerable institution of the orphanage to Wollishofen as a form of compensation for the forcible incorporation the commune had undergone.

Wollishofen today

Do the scars from that time still persist? No. Almost no-one is aware of the injustice that Wollishofen suffered back then. Nevertheless, Wollishofen might have been more careful with its inheritance. In the 1950s and 1960s and indeed right up until the present day, all too much of its historic fabric has been sacrificed with seemingly little thought to a development that threatens to transform Wollishofen into a faceless residential district.

Inevitably, the former farmers’ gardens have vanished, and of course the few remaining industrial buildings have been put to new uses. Wollishofen’s rare treasures on the lake shore – the Mythenquai baths, the Saffa-Inseli, the community centre on Bachstrasse, the Rote Fabrik along with the Weisse Fabrik, the lake restaurant and the Fischerstube – may not be under direct threat; but in the residential areas, densification threatens to destroy the district’s quality of life.

Whatever the future holds, everyone now accepts that Wollishofen is part of the city.

Dr. Sebastian Brändli, historian

www.wollipedia.ch

March 2022

You can also find the Wollipedia blog on our Zurich Open Platform (ZOP).

Header image: Wollishofen in around 1900 on a picture postcard (ZB Zürich)