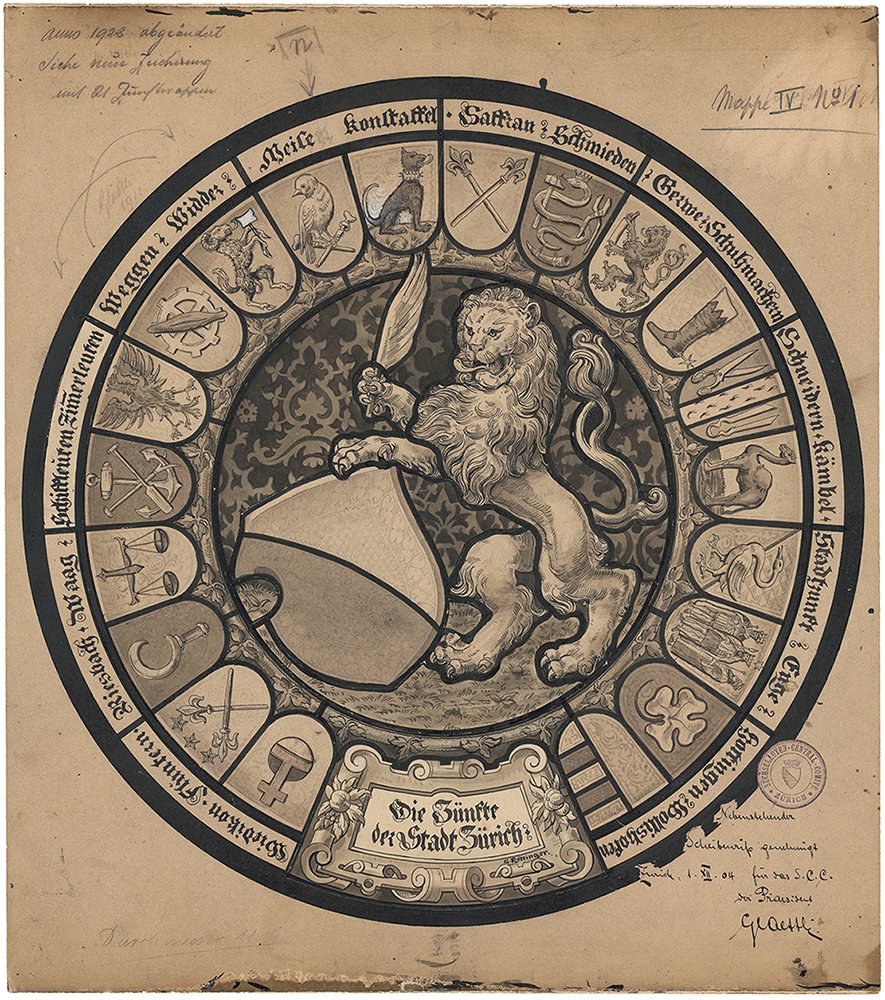

The guilds of Zurich

Every April, the guilds of Zurich don their costumes, saddle up their horses, decorate their floats and celebrate the ‘Sechseläuten’ spring festival. We explore the political and social importance held by the guilds in the past, shine a light on their peculiarities and customs – and reveal how they evolved from state-sponsored craftsmen’s organisations into private associations.

The ‘Sechseläuten’ in the past

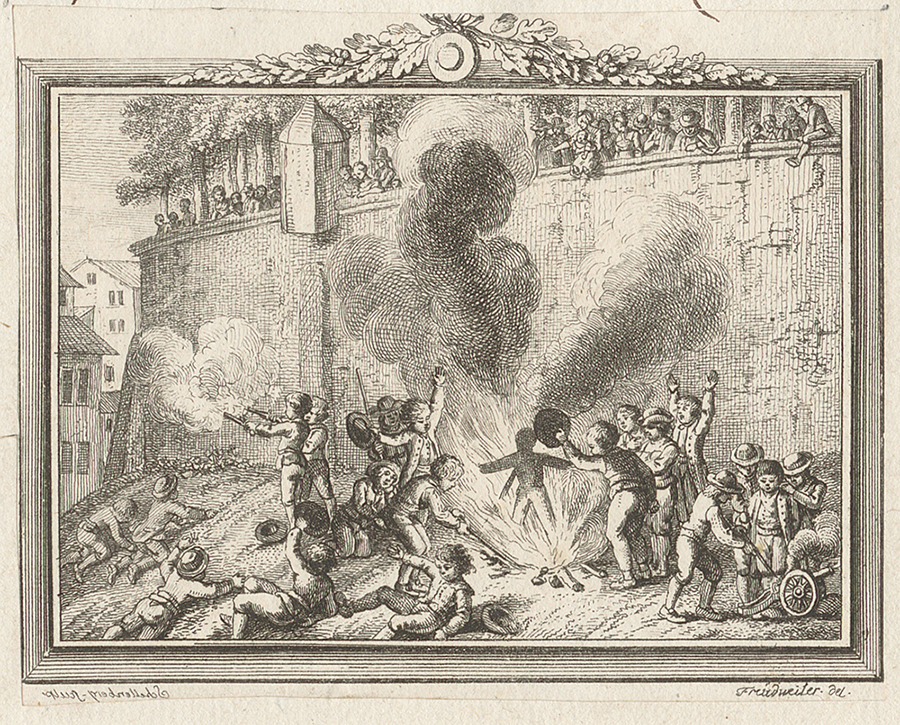

Records of the ‘Sechseläuten’ – the ringing of the Grossmünster’s second-largest bell in the evening after the equinox at the end of March – date back to 1525. This end-of-work bell let everyone know that the working day would be ending later once again. Traditionally, young people gathered with fireworks and drums, lit bonfires and burned straw dolls, while the adults said goodbye to the winter with meals hosted by the guilds.

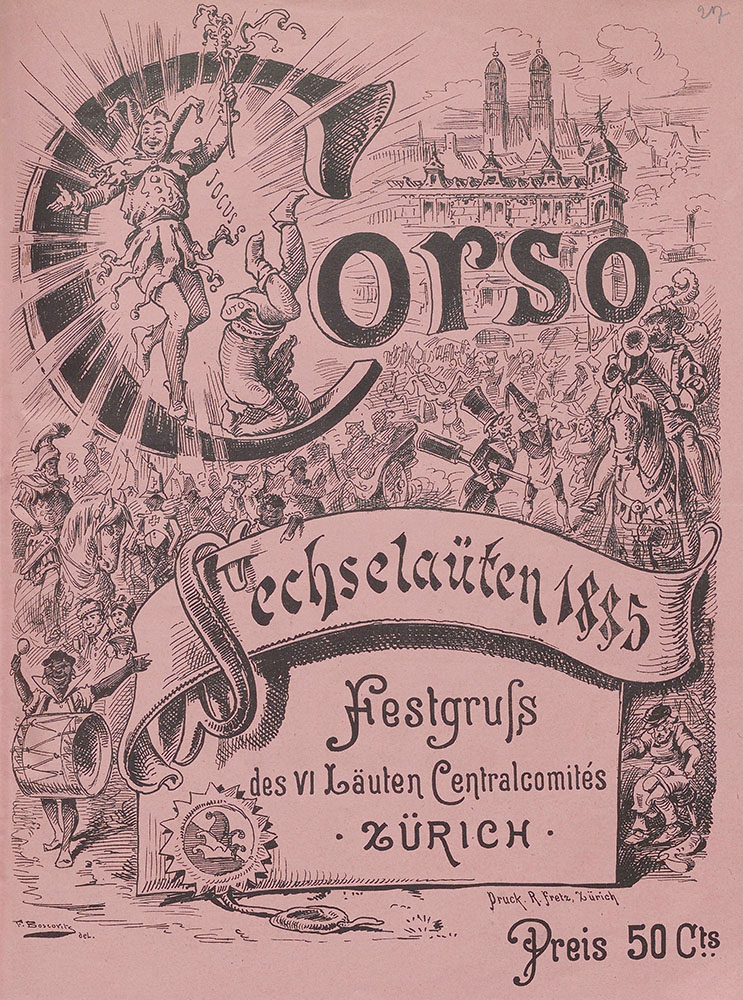

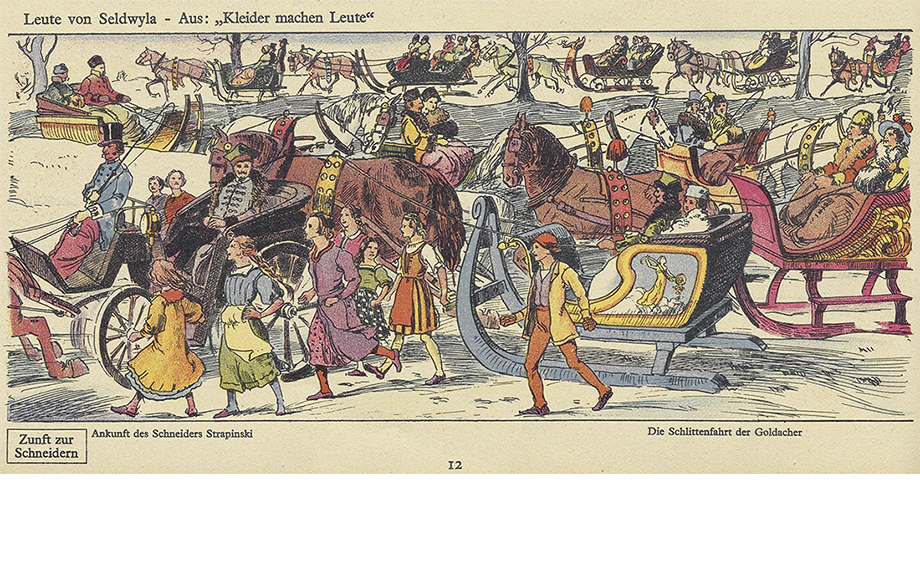

The holiday as we know it today, with the procession of children and guilds, gifts of flowers and the burning of the Böögg, a snowman-like figure, did not come into being until the 19th century – in parallel with the guilds’ declining political power. It has its roots in the costumed parade organised by the ‘Meisen’ Guild in 1818. On the evening of the Sechseläuten in 1819, additional guilds marched through Zurich with music and torches and visited each other. A joint procession was held in 1839, which evolved into parades with patriotic, historical and literary influences.

Hear what the Zurich poet Gottfried Keller and the Illustrirte Zeitung magazine wrote about the Sechseläuten:

The constitution of Zurich’s guilds

The city of Zurich was shaped by guilds for four and a half centuries.

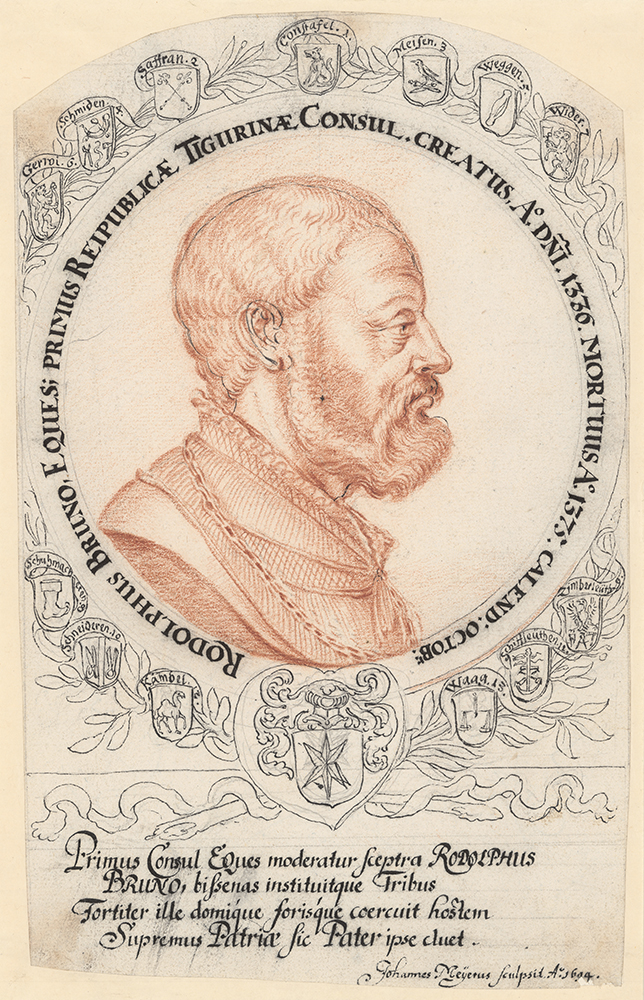

In the mid-14th century, the priest John of Winterthur recorded in his Chronicle that ‘a great and dangerous uprising had bubbled out of the spring of injustice in the city of Zurich ’ in 1337. Inhabitants were protesting against the unfair administration of justice and attacked the greedy councils ‘with great anger and violence’. The ruling four knights and eight citizens were stripped of their power and replaced by a mayor and a council of knights, citizens and – in a new development – craftsmen.

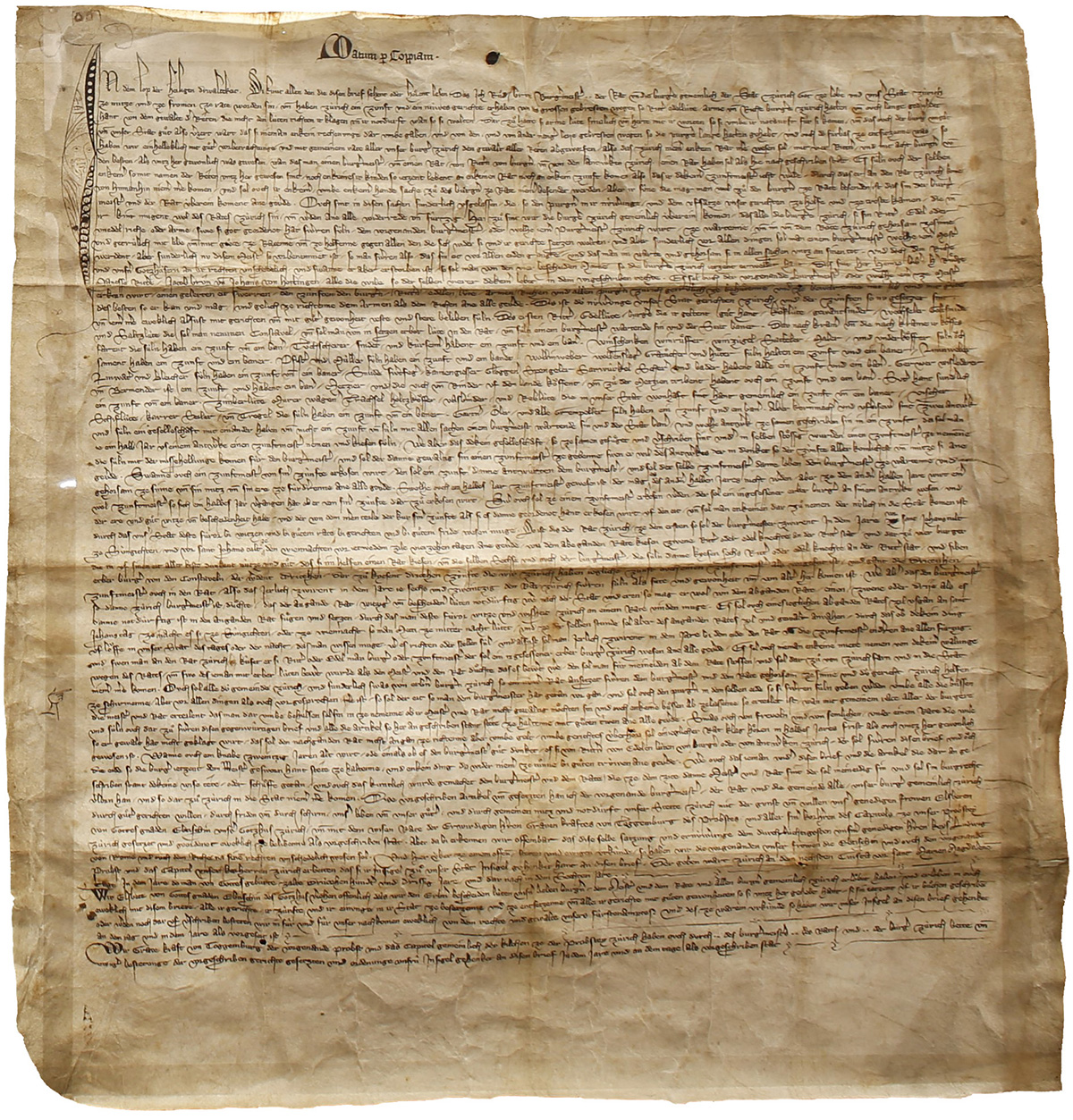

This Brun’sche Guild Revolution, which actually took place in 1336, marked the birth of Zurich’s ‘political’ guilds. The First Sworn Charter took the professions and crafts that were now included in the city’s government and categorised them into 13 larger groups, for example by combining carpenters and winegrowers.

Until 1798, these ‘umbrella organisations’ of guilds played a fundamental role in the city of Zurich – alongside the old ruling class, which was assigned to the ‘Gesellschaft zur Constaffel’

The guilds: politics, economy and society

Zurich’s guilds were political, economic and social institutions.

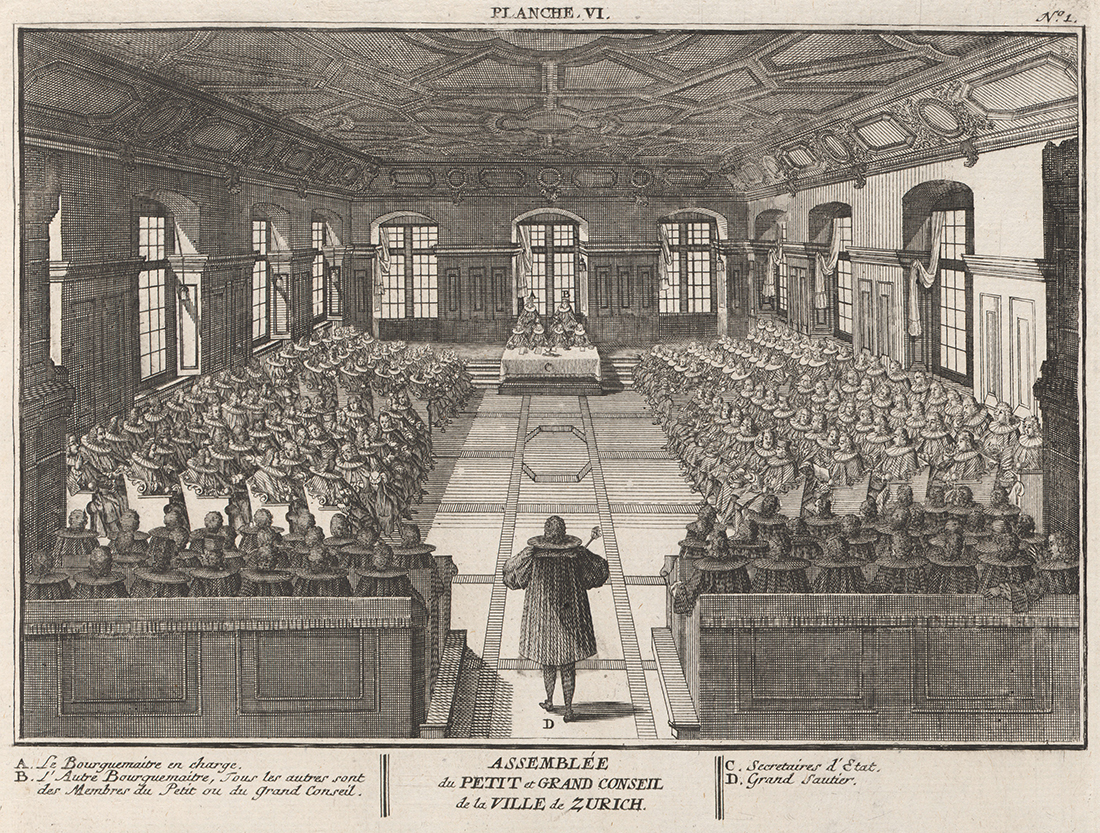

Each elected representatives from among its ranks to serve on the Minor Council and the Grand Council. For this reason, guild membership and family ties – along with a financial buffer and a suitable character – played a crucial role for anyone wanting a political career in Zurich. The power of the guilds extended to the countryside via councillors, who were appointed as governors.

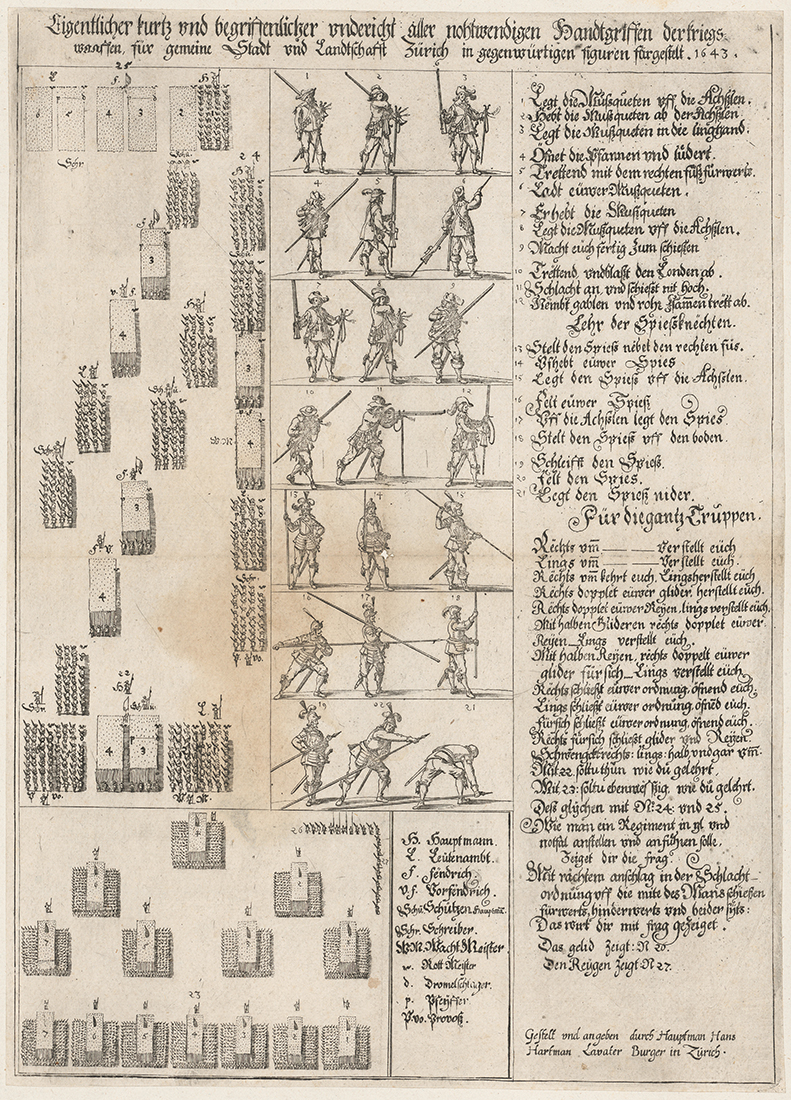

As administrative districts on a municipal level, they were responsible for military, fiscal and administrative tasks. Until the 17th century, for instance, each guild had a banner with its own flag and was responsible for physical tests, exercises and the youngest military conscripts.

‘The guilds were service organisations of various kinds.’

Otto Sigg, former State Archivist of Zurich

How long did the apprenticeship and journeyman periods last? Who was allowed to sell what, where? The city of Zurich’s trade businesses aimed to provide everyone with food and an income. The guilds therefore regulated their organisation and their crafts via trade regulations, which were enacted by Zurich’s council.

They supported city residents from cradle to grave, structured their professional life and the course of the year, imposed obligations and duties – and opened their coffers in times of need.

A convivial atmosphere

The 13 guilds were not named in the First Sworn Charter. Instead, their names evolved gradually, for example being based on the taverns where the craftsmen gathered: Kämbel, Meisen, Waag. Men spent a large part of their free time here – working women less so, for societal reasons.

The members of the ‘Meisen’ (literally ‘tit’) Guild, to our knowledge, did not include any bird traders and the retailers in the ‘Kämbel’ (literally ‘camel’) Guild did not transport their goods on camels. The ‘Widder’ (literally ‘aries’) Guild is associated with butchers or cattle traders: this name also comes from their tavern. The names Saffran (saffron) and Weggen (bread) actually represent the products of these guilds.

The other names go back to the industry that dominates the guild as a whole: tanners, shipmen, smiths, tailors, shoemakers, carpenters. Because of their tavern, the Shipmen’s Guild was alternatively called the guild ‘zum goldenen Engel’ and ‘zum goldenen Anker’, while the tanners were dubbed the guild ‘zum roten Löwen’.

Move the mouse over the orange-coloured houses and find out where each guild had its tavern in the 16th century:

The 12 old guilds and the Constaffel

While most old documents use masculine terms to refer to guild members, this is deceptive: women engaged in the professions were also included. From 1490 onwards, all male citizens and unmarried female citizens of the city of Zurich had to be in a guild or the Constaffel. From 1525, people were only allowed to be a member of one guild.

As the city-state grew, craftspeople’s political participation declined. In the 17th century, a ‘class system’ developed, with more and more power shifted to a small number of Zurich families who were able to join the council. According to Otto Sigg, an upper class formed in the guilds, which soon no longer had much in common with their base of tradespeople.

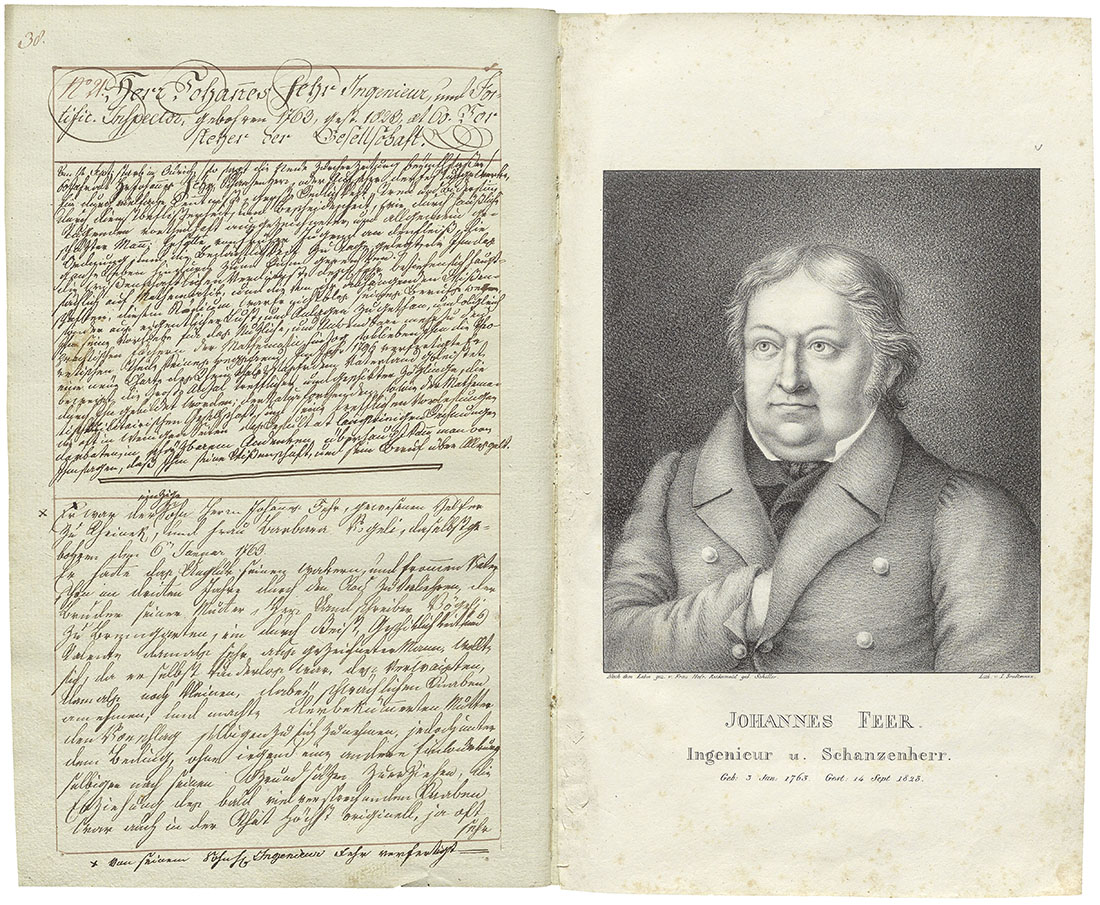

Here are brief portraits of the 12 guilds, following the order listed by Mayor Rüdiger Manesse, which applied from 1361 to 1798. Prior to this, the ‘ranking’ of the guilds had changed several times, depending on their social status.

‘Saffran’ Guild

The ‘Saffran’ (literally: ‘saffron’) Guild encompassed shopkeepers, decorative metal-workers, needle-makers, bag-makers, trimming-makers, button-makers, wool-knitters, hat-decorators, brush-binders and comb-makers of both sexes, as well as pharmacists, dentists and confectioners.

According to Otto Sigg, some innovations were initially seen as threats. In 1670, the trimming-makers came before the Council to accuse a highly advanced foil tape factory – run by a non-guild member in Feuerthalen – of being a shoddy operation.

The guild had the largest number of members in the 18th century, since it combined the liberal professions (merchants, clergymen, glass painters, goldsmiths) with retailers. As an electoral tactic, certain families from these independent trades spread themselves across different guilds. The theologian Johann Caspar Lavater was a member of the ‘Saffran’ Guild.

‘Meisen’ Guild

The ‘Meisen’ Guild comprised three unequal trades – the wine-makers, the saddlers and the painters – each of which had their own trade regulations. The wine-makers’ regulations governed who was allowed to sell wine and who was allowed to serve wine, for instance.

Most of Zurich’s surface painters and artistic painters worked here, while stained glass painters were allowed to join any guild. According to Markus Brühlmeier, the ‘Meisen’ Guild occasionally reserved the right to reject candidates from independent trades who did not meet their requirements. The art school director Johann Balthasar Bullinger was a member of the ‘Meisen’, and before him, the reformer Heinrich Bullinger had also belonged to the guild.

When the guild set about building a new guild house in 1751, six Messrs Escher and five Messrs Landolt sat on its board of directors and building committee.

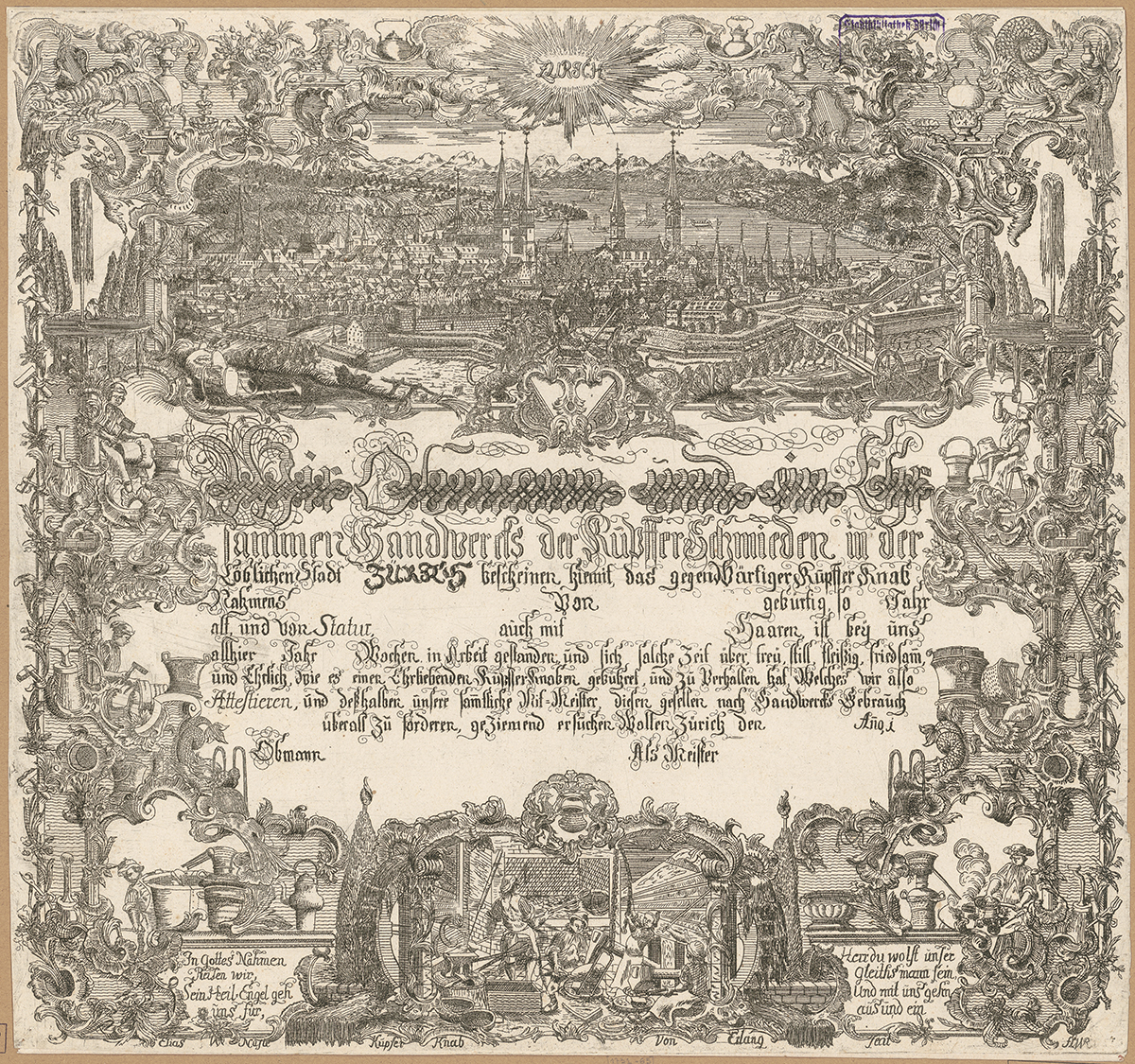

Smiths’ Guild

The Smiths’ Guild included blacksmiths, sword-forgers, bell and pot founders, plumbers, locksmiths, armourers, grinders and watchmakers, as well as shearers and barbers (beard-shearers, surgeons, masseurs, cuppers).

Like the bakers and millers, this guild also had two taverns: the shearers and barbers bought their own property in 1534 and called themselves the ‘Gesellschaft zum Schwarzer Garten’ (‘Society of the Black Garden’). The others gathered in the ‘Goldenen Horn’ (‘Golden Horn’) – hence the horn in the coat of arms.

The Füsslis, who were bell founders, belonged to this guild, of course, but so did the baroque artist Anna Waser, due to her father. The politician Johann Heinrich Waser, the history professor Johann Jakob Bodmer and the librarian and statesman Johann Konrad Heidegger were among the members of the Smiths’ Guild during the 17th and 18th centuries.

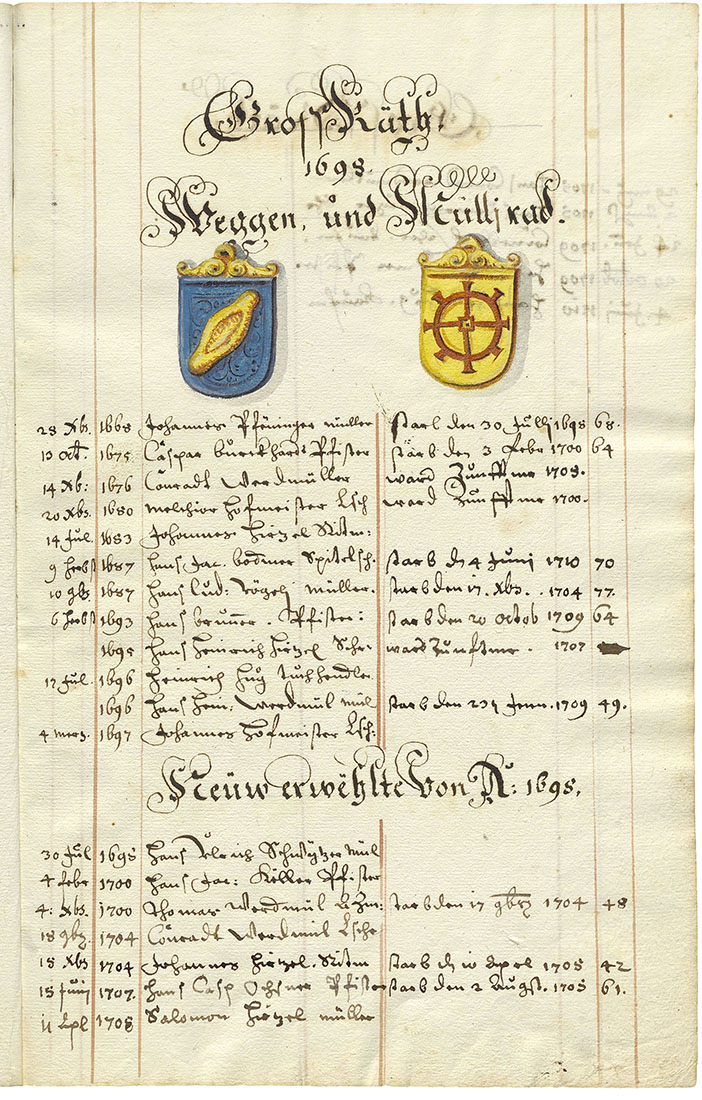

‘Weggen’ Guild

Bakers, bread sellers and millers were split into two groups: the ‘Weggen’ (literally: bread) Guild and the ‘Gesellschaft zum Müllirad’ (the ‘Mill Wheel Association’). Both provided a number of councillors, had their own tavern and their own coat of arms.

It was not possible to join more than one guild: if a miller was elected master of the ‘Weggen’ Guild, he had to change his guild and his trade.

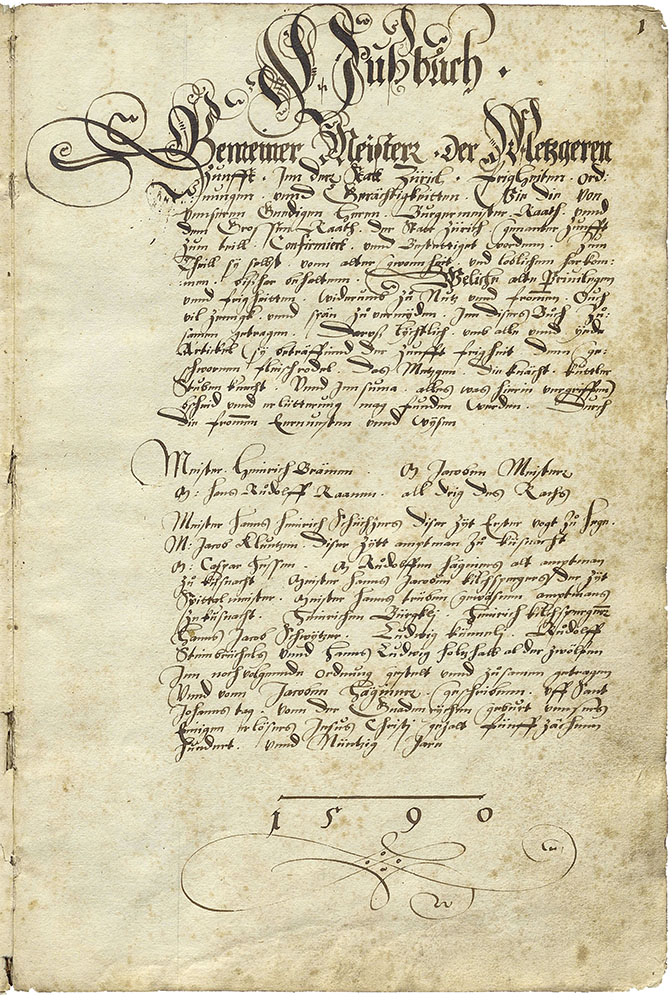

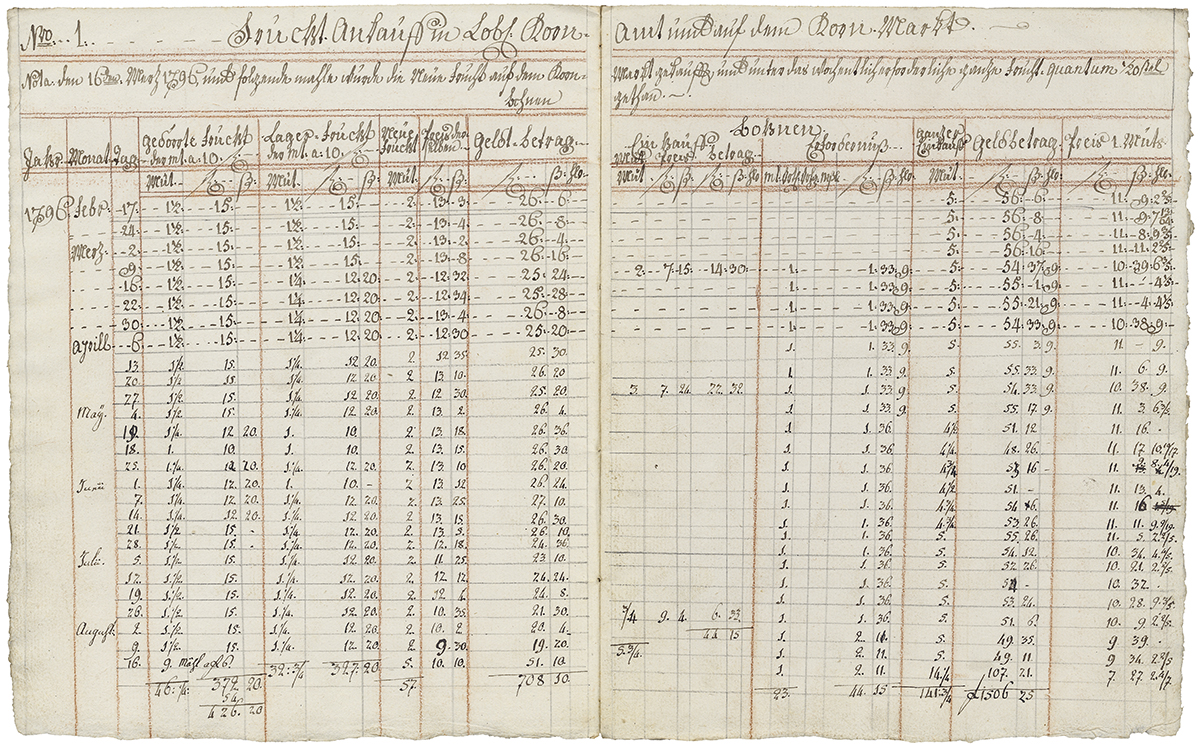

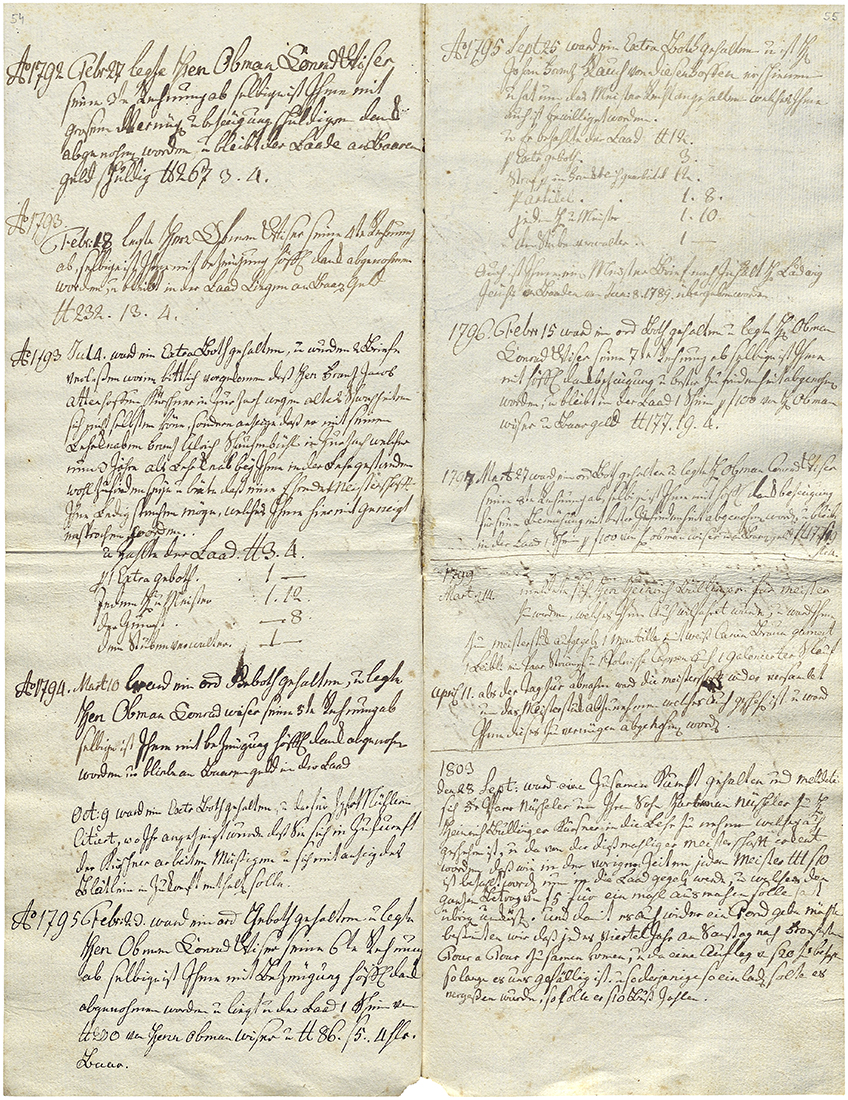

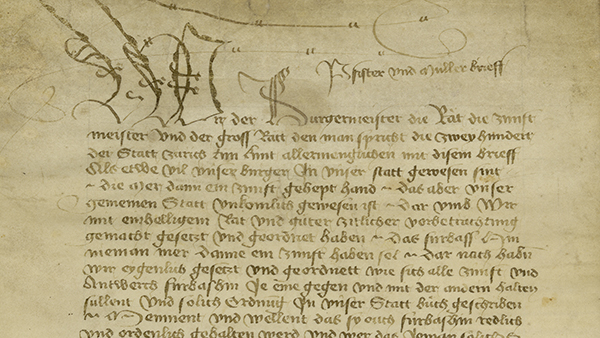

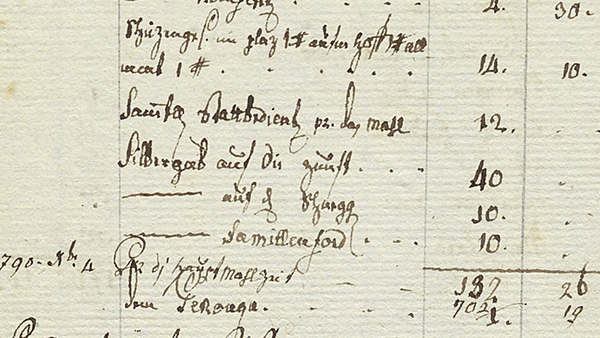

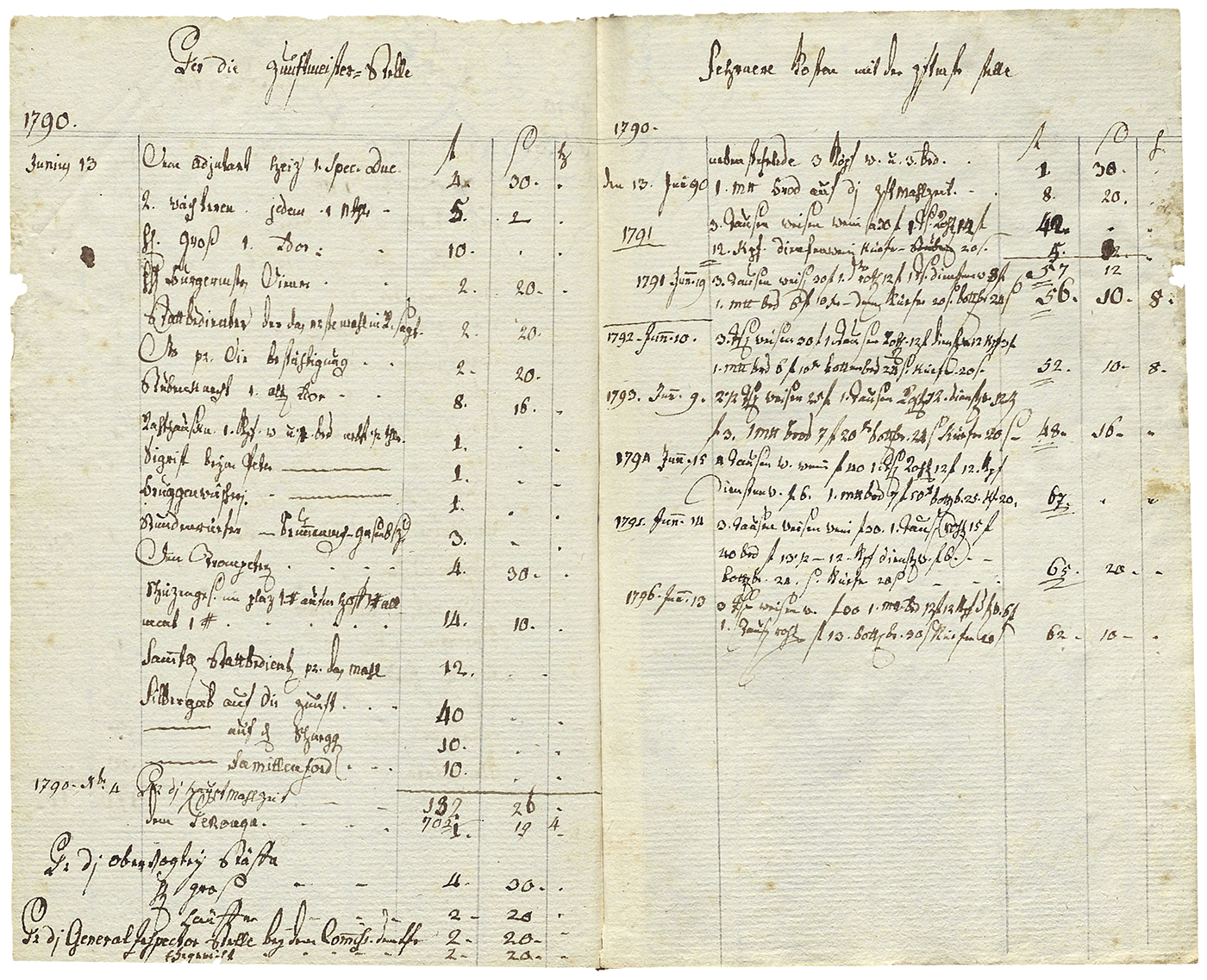

The guild archive stored at ZB Zürich records the organisation and history of both the guild and the craft itself (from the apprenticeship, to the journeyman years and finally masterhood) via documents, minutes, letters, registers and accounting books from the 14th to the 21st century.

We recommend the monograph Mehl und Brot, Macht und Geld im Altes Zürich (Flour and Bread, Power and Money in Old Zurich) by Markus Brühlmeier.

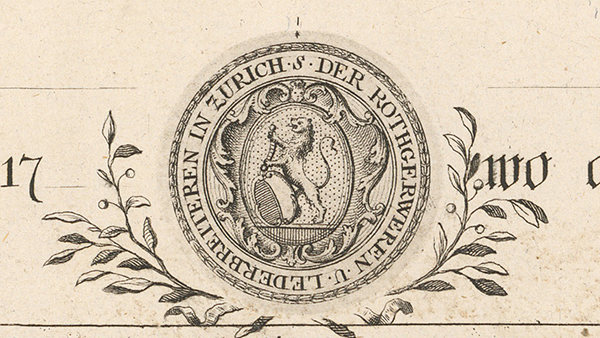

Tanners’ Guild

The coat of arms of the Tanners’ Guild, which used to gather in the ‘Roten Löwen’ (‘Red Lion’), depicts a rampant red lion with a scraper in its claws. This guild included tanners, curriers and parchmenters.

Conflicts of interest can arise where different industries work with the same material, such as fur or leather. In the event of disputes between tanners, fur traders, hat-decorators or shoemakers, clarification needed to be given in terms of who was allowed to work with which material and how.

A case from the 16th century shows that the guilds’ monopoly could inhibit innovation: when Moroccan-style tanning was undertaken outside the guild, it was first banned and subsequently only members of the guild were permitted to practice it.

‘Widder’ Guild

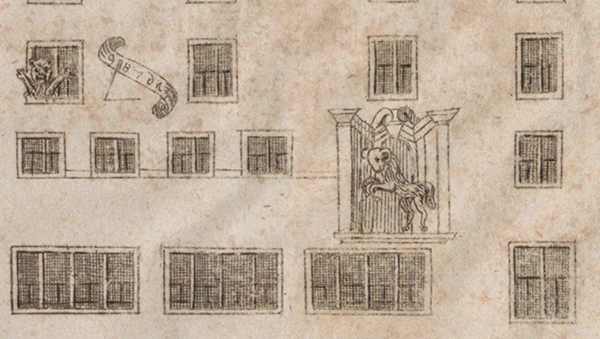

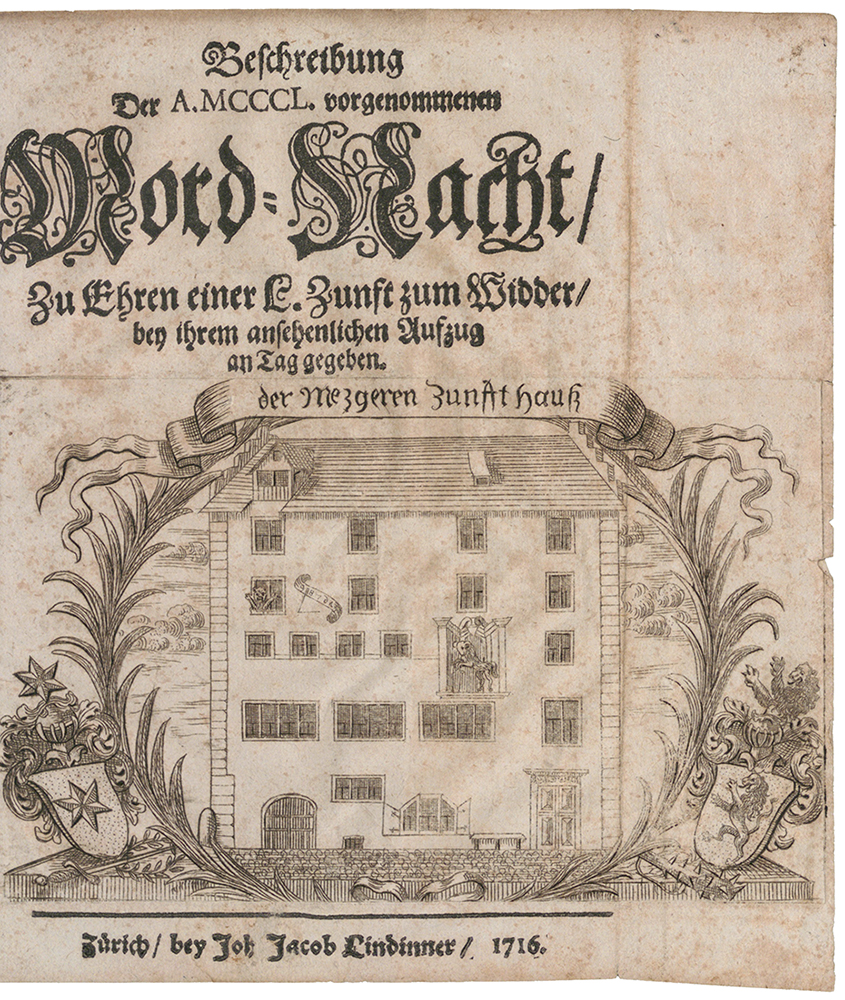

The butchers, tripe-sellers and cattle traders formed the ‘Widder’ Guild. From its files, some of which are also stored in the Zentralbibliothek Zürich, it is possible to trace back the line of guild masters to 1336 with very few gaps. Every mayor from 1601 to 1669 was a member of the ‘Widder’ Guild.

The number of ‘meat shops’ was regulated to ensure their quality standards and protect the livelihood of the city’s master butchers.

In the Zurich Annals, the ‘Widder’ are closely linked to the ‘night of murders’ in 1350, when they bloodily crushed the coup of the nobles (who had been expelled in 1336) against the new council and its supporters. The tragic escalation shaped the relations between the social classes and political groups within the city. In writings, pictures and their Ash Wednesday procession, the ‘Widder’ celebrated their ‘lion-like courage’.

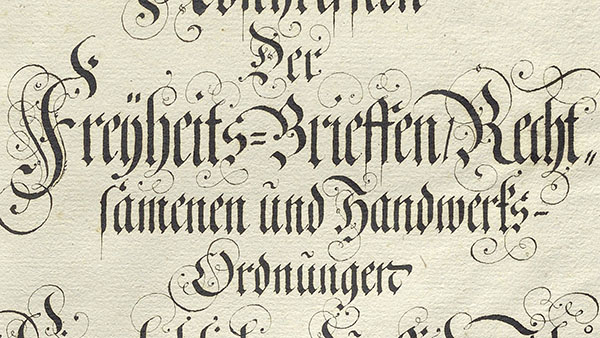

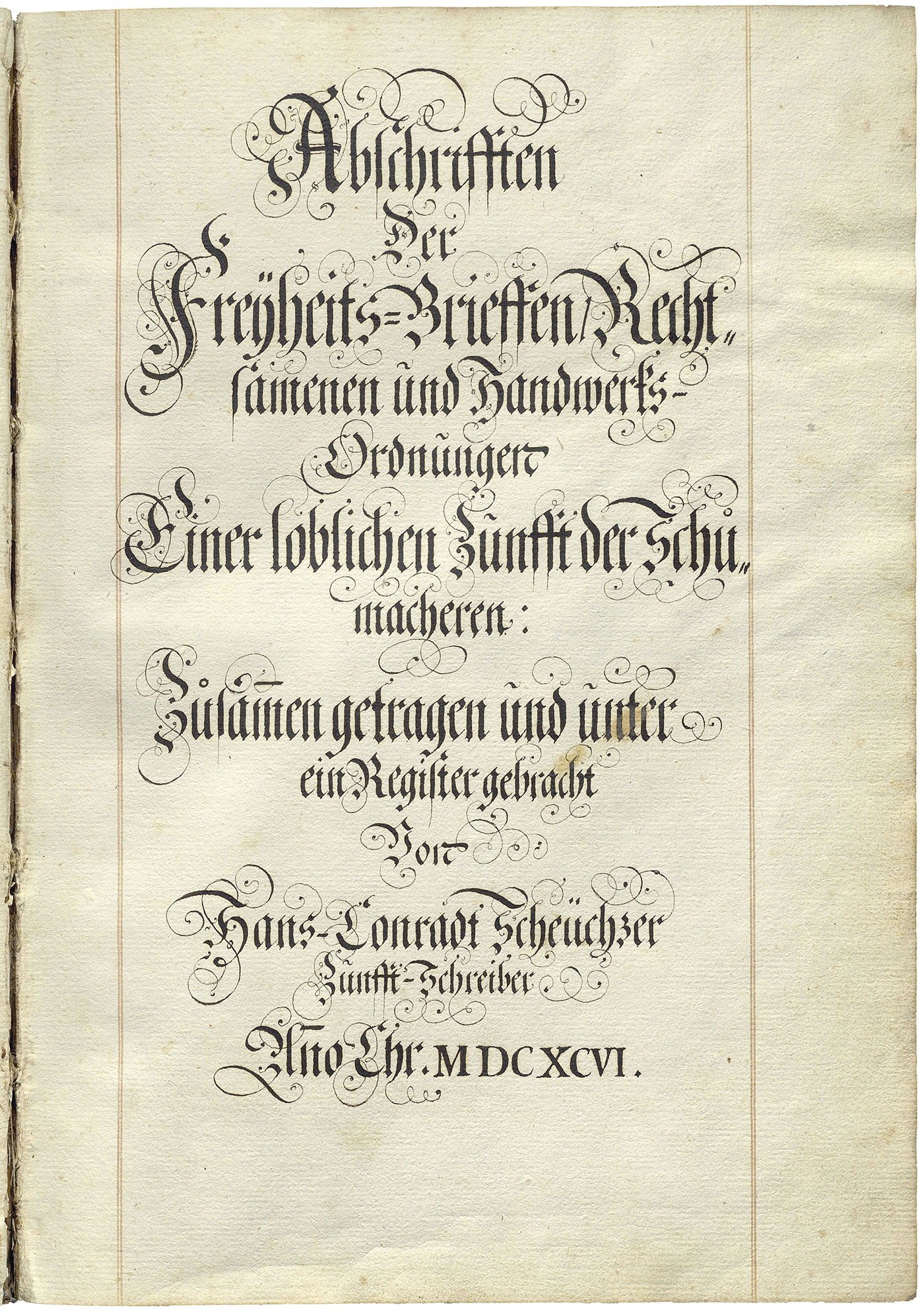

Shoemakers’ Guild

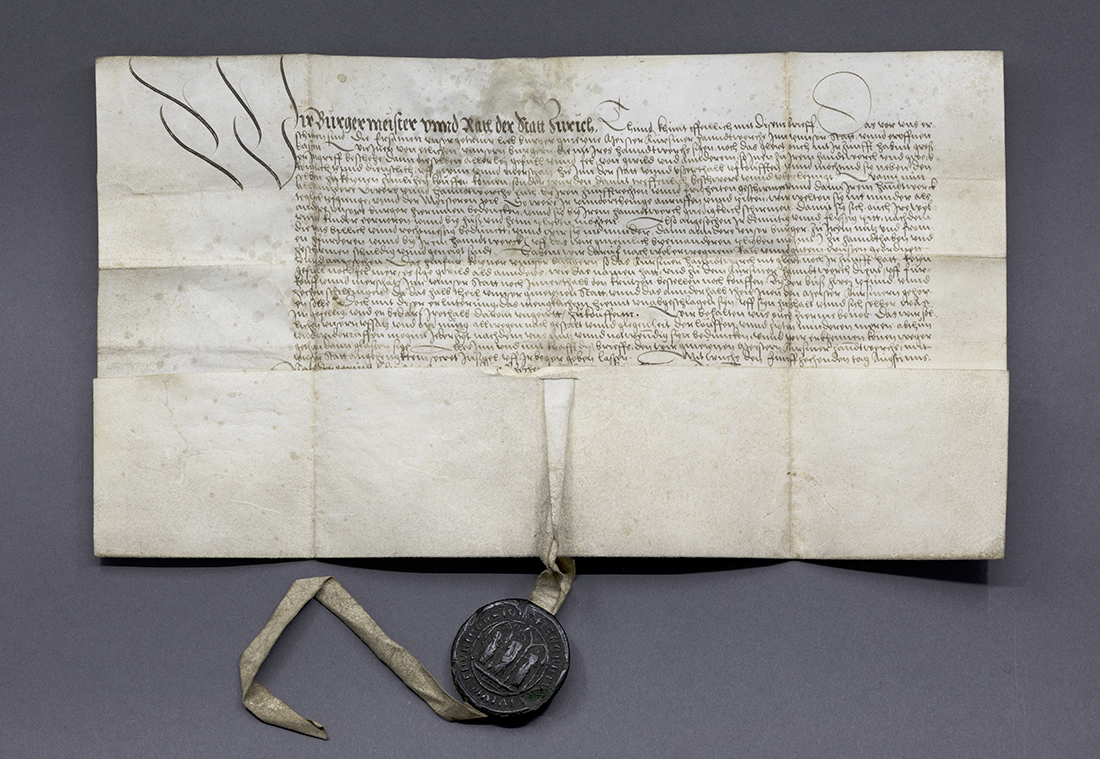

The Shoemakers’ Guild was the only one to include just one craft. It is not surprising that it occasionally came into conflict with the tanners, who also worked with leather. Thus, the collection of ‘Freyheits-Brieffen, Rechtsamenen und HandwerksOrdnungen Einer laöblichen Zunfft der Schumacheren’ (‘Letters of freedom, legal treatises and handicraft regulations for the shoemakers’ guild’, 1696) by guild clerk Johann Konrad Scheuchzer states that only shoemakers are allowed to sell dyed leather.

It was also important for them to distinguish themselves from the shopkeepers. In 1560, the shoemaker Heinrich Anderes was instructed not to sell his shoes in the street or in an alleyway: like the other shoemakers, he was only permitted to do so in a shop.

In 1877, the shoemakers and the tanners merged to form the United Tanners’ and Shoemakers’ Guilds.

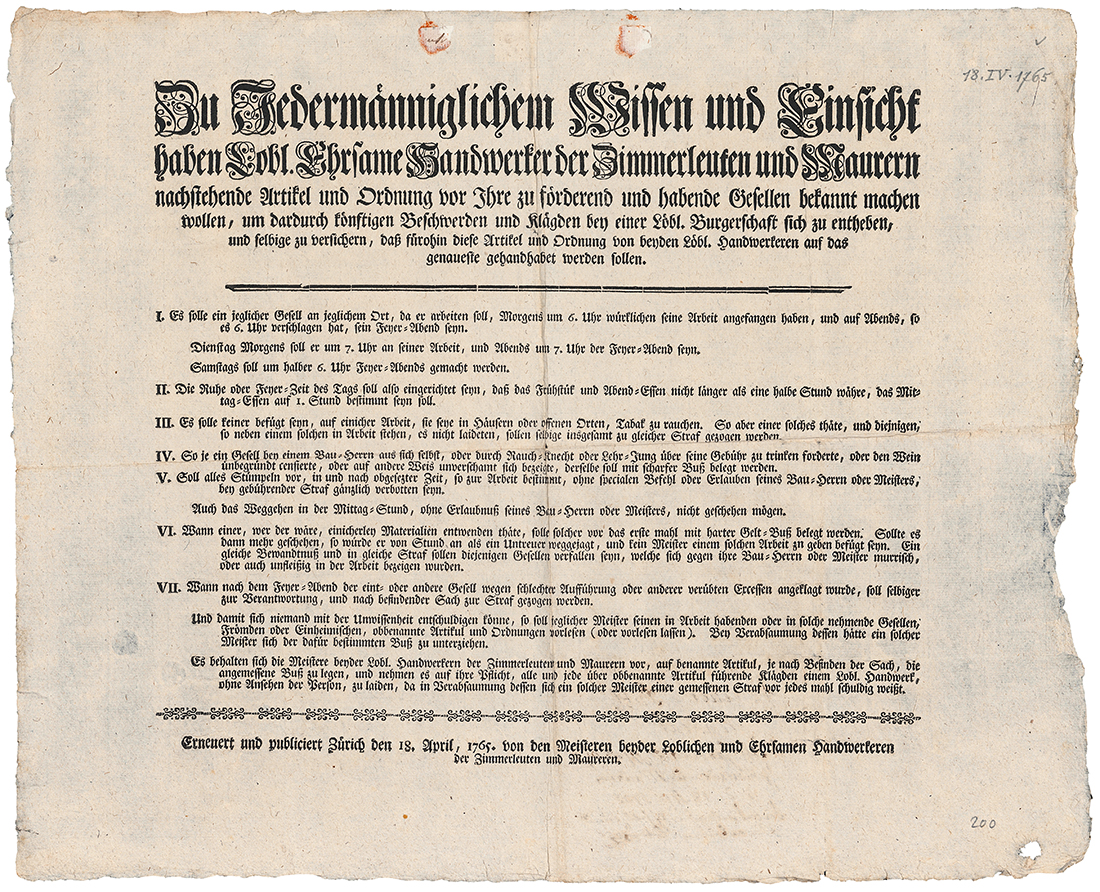

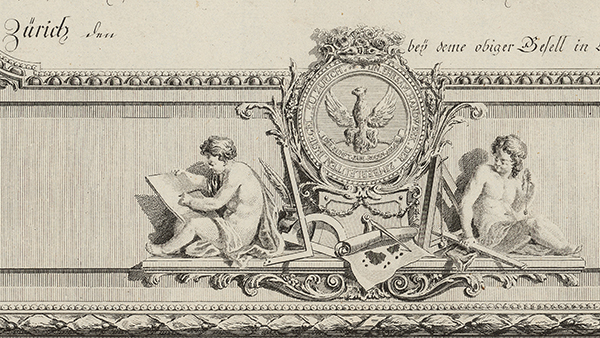

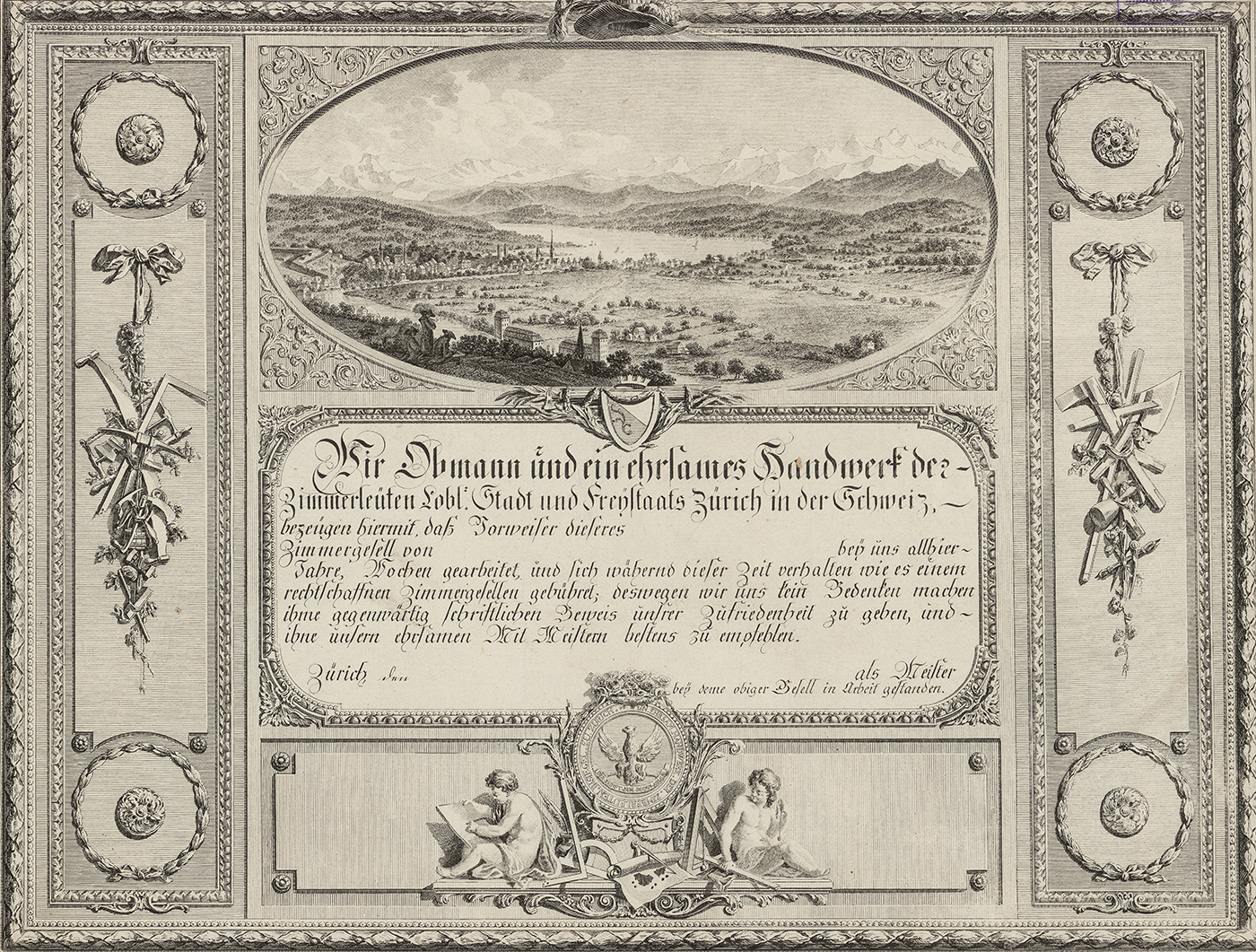

Carpenters’ Guild

Carpenters, bricklayers, joiners, stonemasons, coopers, bucket-makers, woodturners, wainwrights, potters, wood buyers and winegrowers (not to be confused with the wine-makers in the ‘Meisen’ Guild) had their tavern in the ‘Rote Adler’ (‘Red Eagle’) – which is why this bird adorns their coat of arms. The guild house on Limmatquai was rebuilt twice: in 1708, to replace the wooden building, and in 2007 after a fire.

The records also list female guild members, especially widows. The previous guild masters include the general, bookseller and publisher Hans Heinrich Bodmer – who was initially celebrated before being disgraced –and the wine merchant and cultural promoter Salomon Klauser-Meyer.

Over the centuries, this guild of tradespeople also opened up to non-professionals – not least for electoral purposes: thanks to Hans Jakob Escher, it gained its first mayor in 1711.

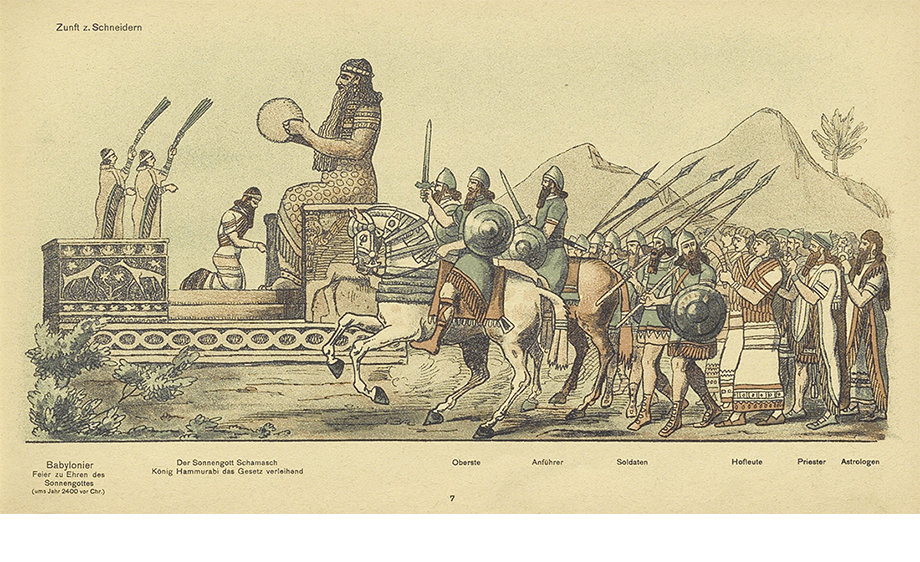

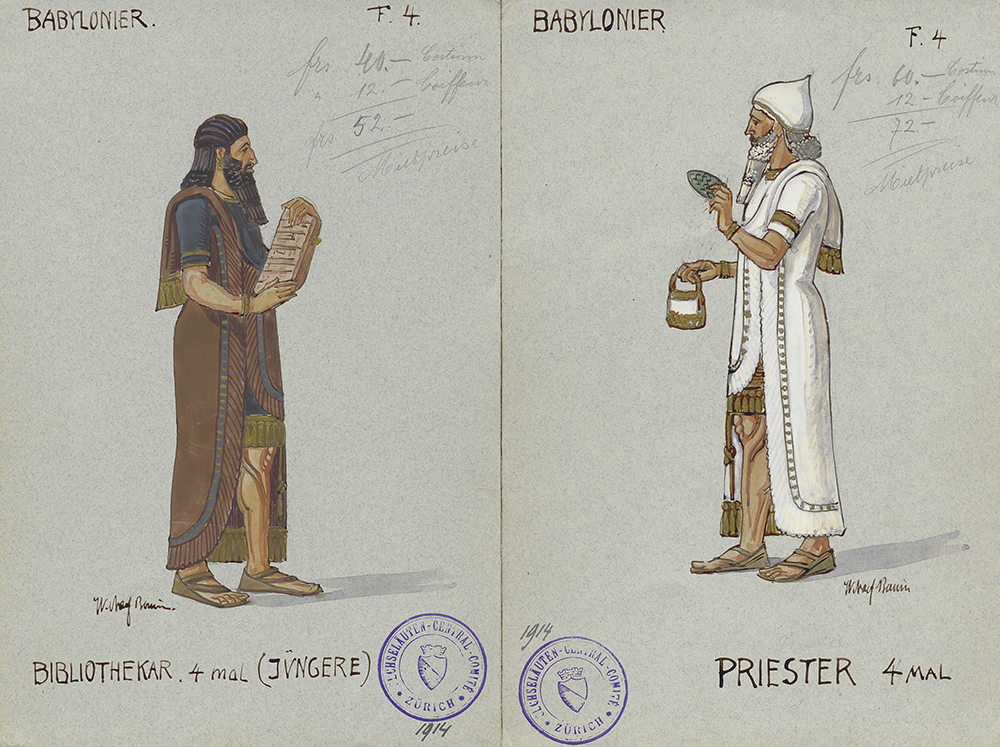

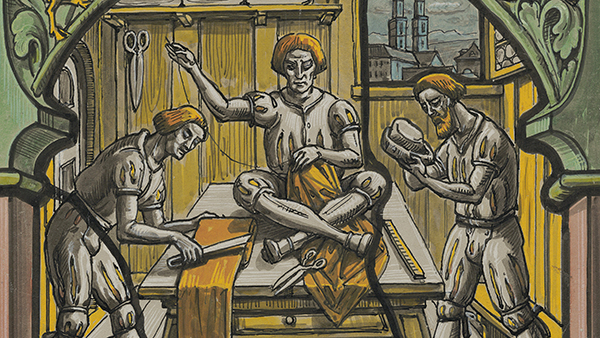

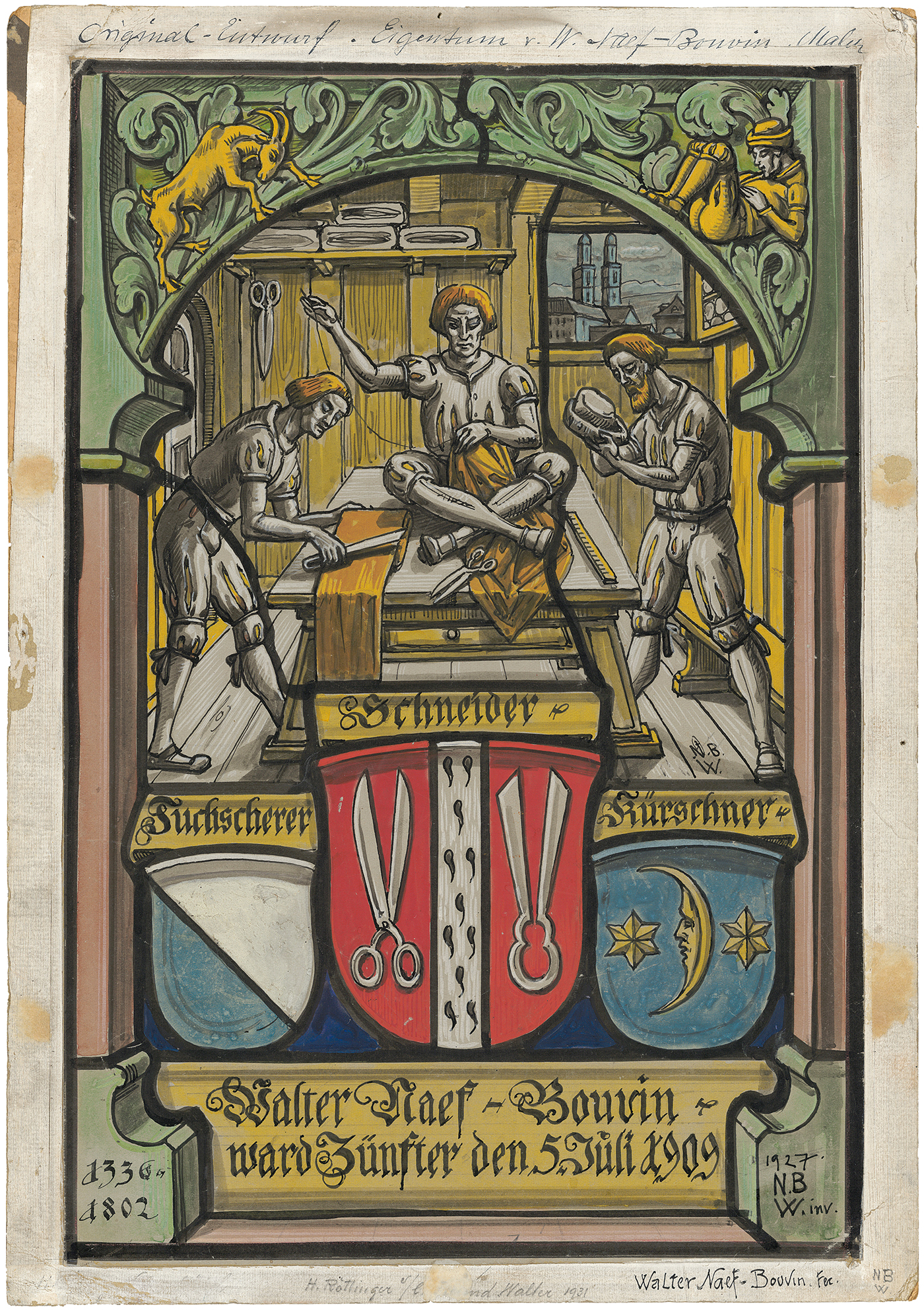

Tailors’ Guild

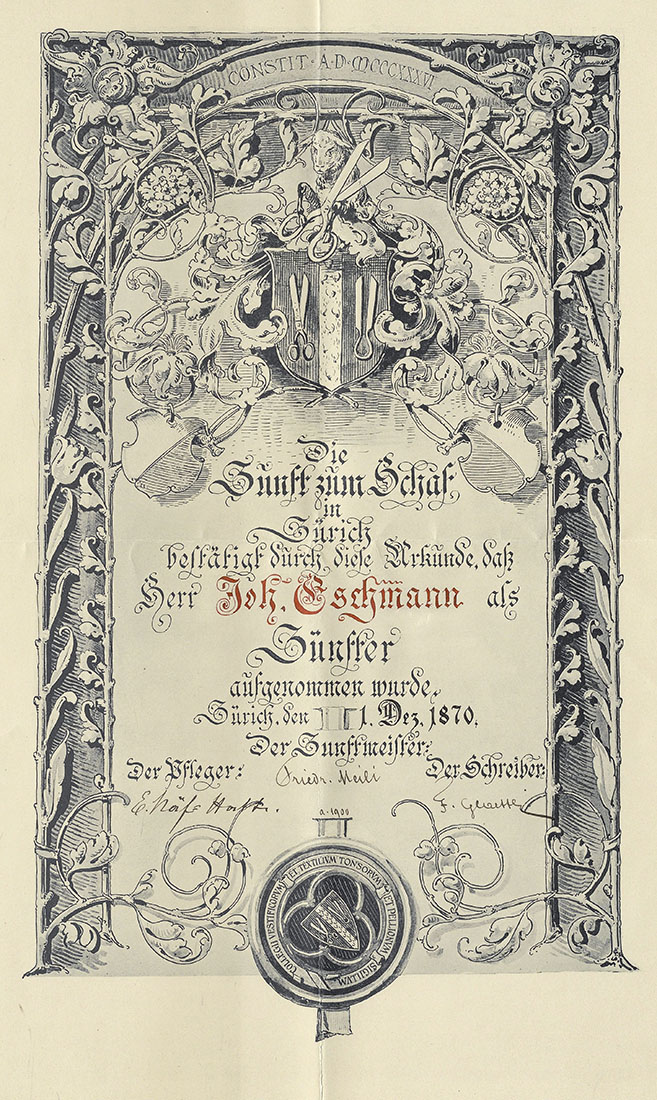

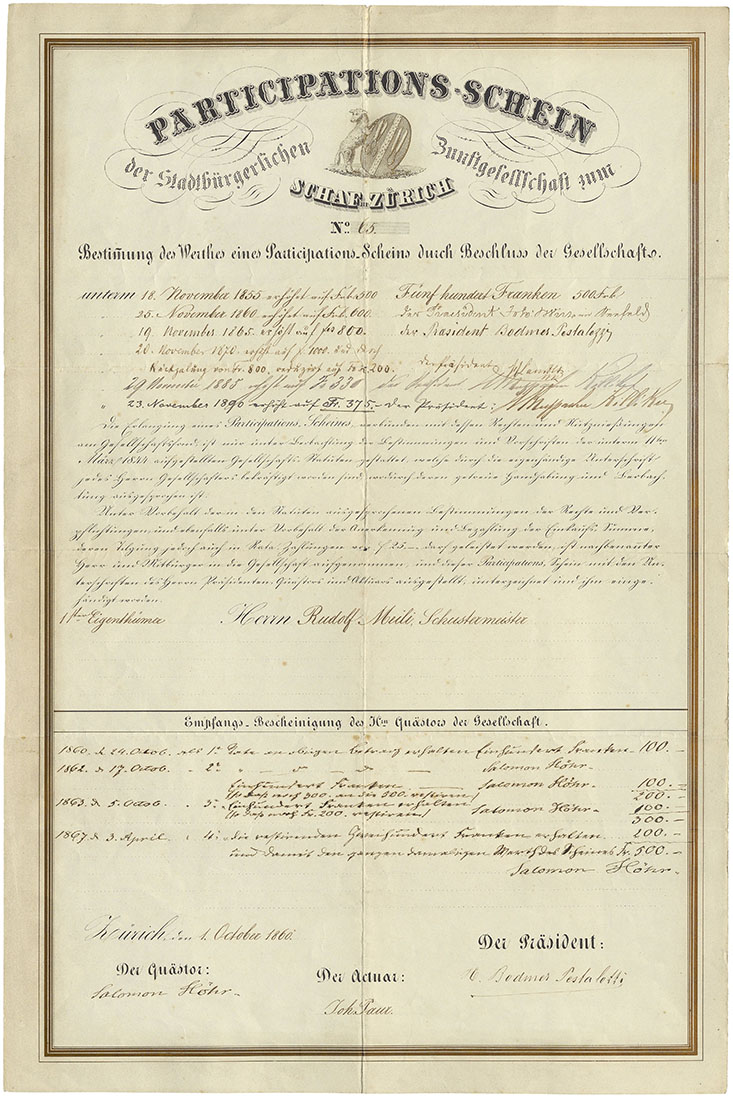

Tailors, furriers, cloth-cutters and their colleagues formed a sizeable trade association as far back as the 14th century. After the Tailors’ Guild moved into the ‘gälen Schaf’ (‘Yellow Sheep’) tavern in 1528, it also called itself the ‘guild of the sheep’.

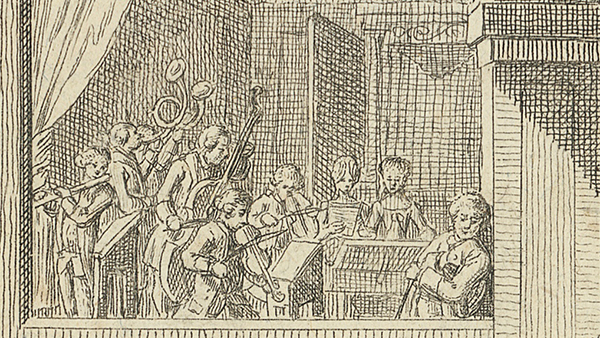

Zurich’s authorities and clergy had rather puritanical concepts of fashion, handed down in moral mandates since the 16th century, which limited the tailors’ haute couture aspirations. The best-known guild-members – even if they did not deal with scissors and irons themselves – include the governor of Greifensee Salomon Landolt and the composer Hans Georg Nägeli.

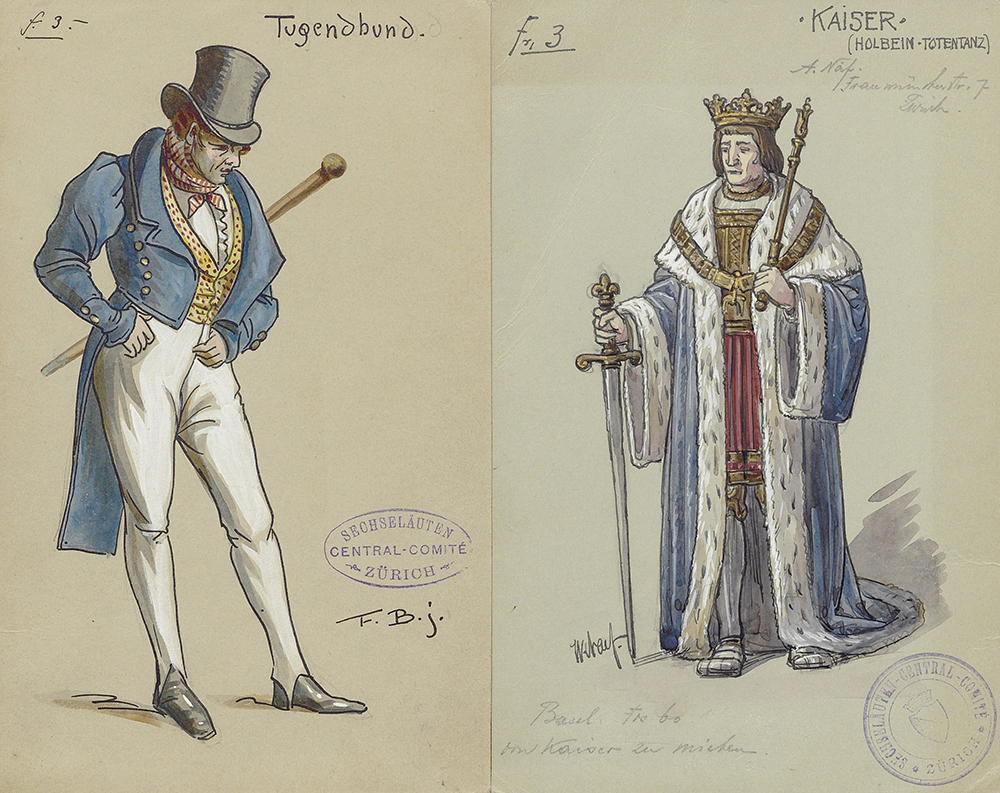

The guild archive, which is held at the ZB Zürich, not only contains costume designs (see picture gallery on the Sechseläuten festival) but also a catalogue of silver tableware from 1597.

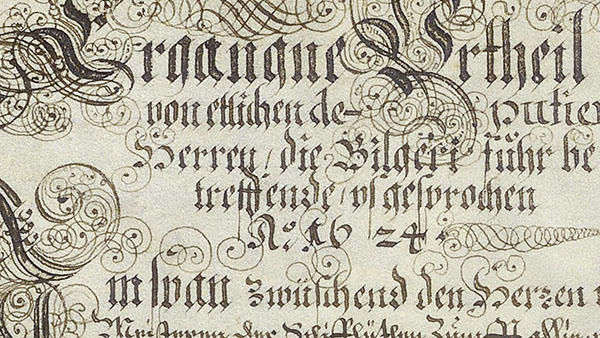

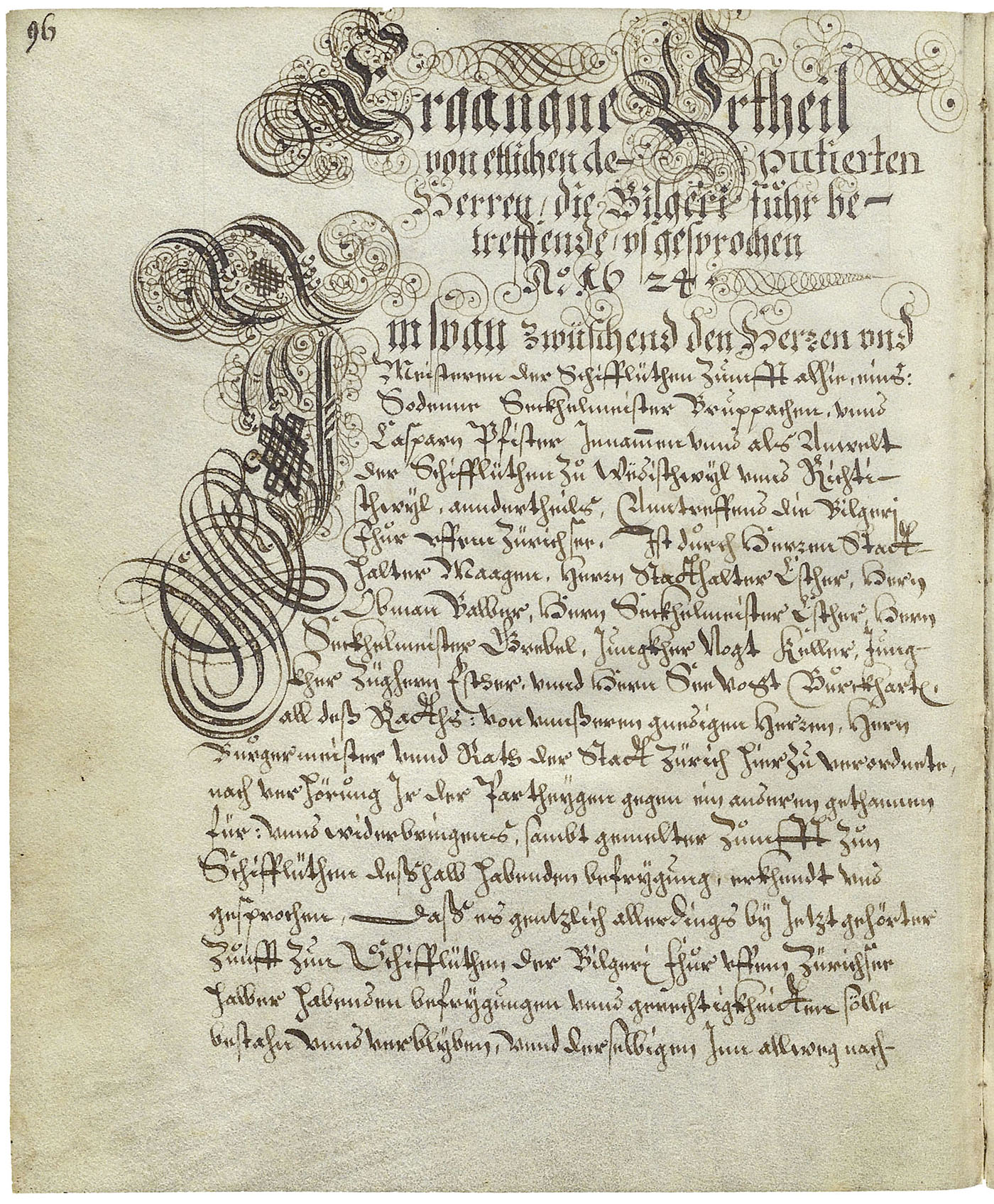

Shipmen’s Guild

The Shipmen’s Guild included shipmasters working on the Niederwasser (Limmat) and Oberwasser (Lake Zurich), Seiler and Fischer. Carriers and porters transporting goods in their wagons or on their shoulders had also belonged to the guild in the past. They had to choose just one of these trades and were not allowed to do double duty.

The guild archives stored in the ZB contain minutes, invoice and interest books, lists of members, letters, files and prints from 1793 to 1931. The collection of chartered ‘freedoms, rights and justices’ on display here comes from the Stadtbibliothek. You could use these documents to look up who was allowed to catch and sell fish or who was responsible for ships carrying pilgrims.

We recommend Thomas Sprecher’s Geschichte der Zunft zur Schiffleuten von Zürich (History of the Shipmen’s Guild of Zurich).

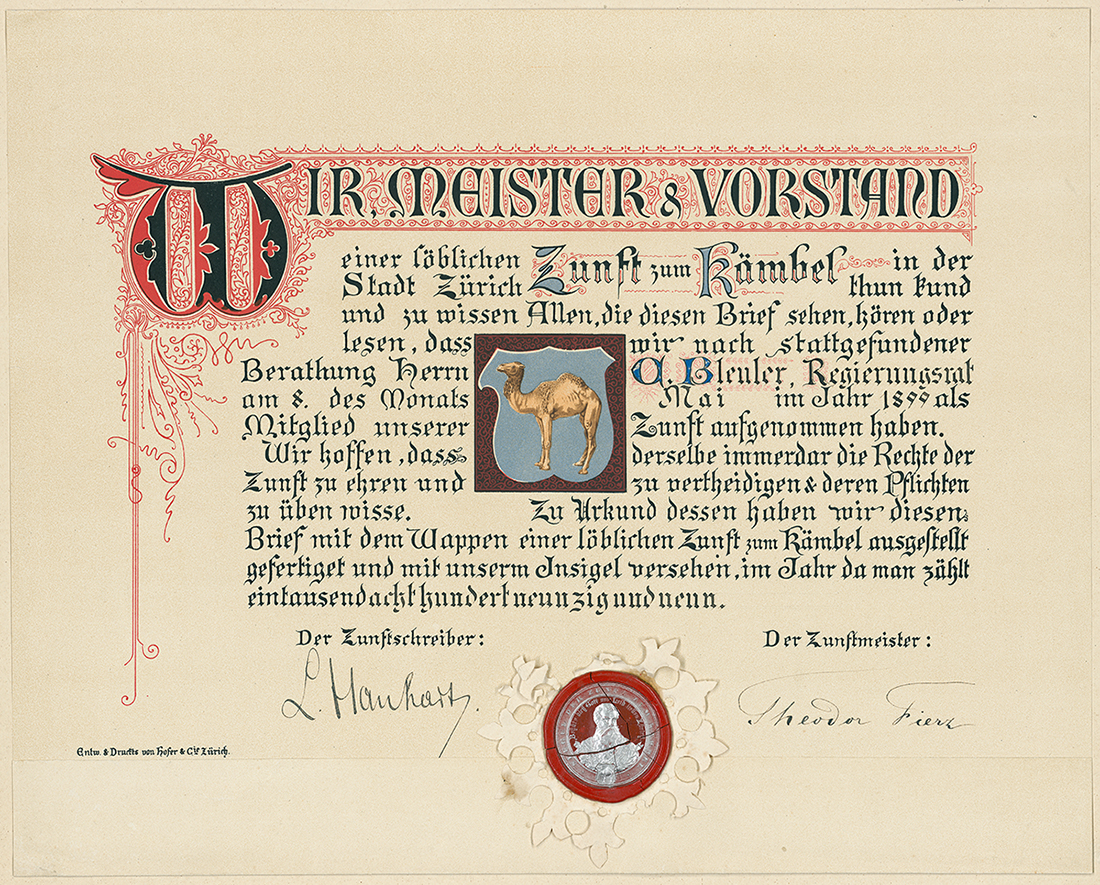

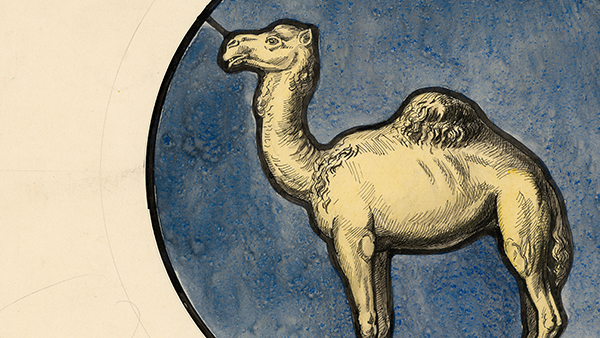

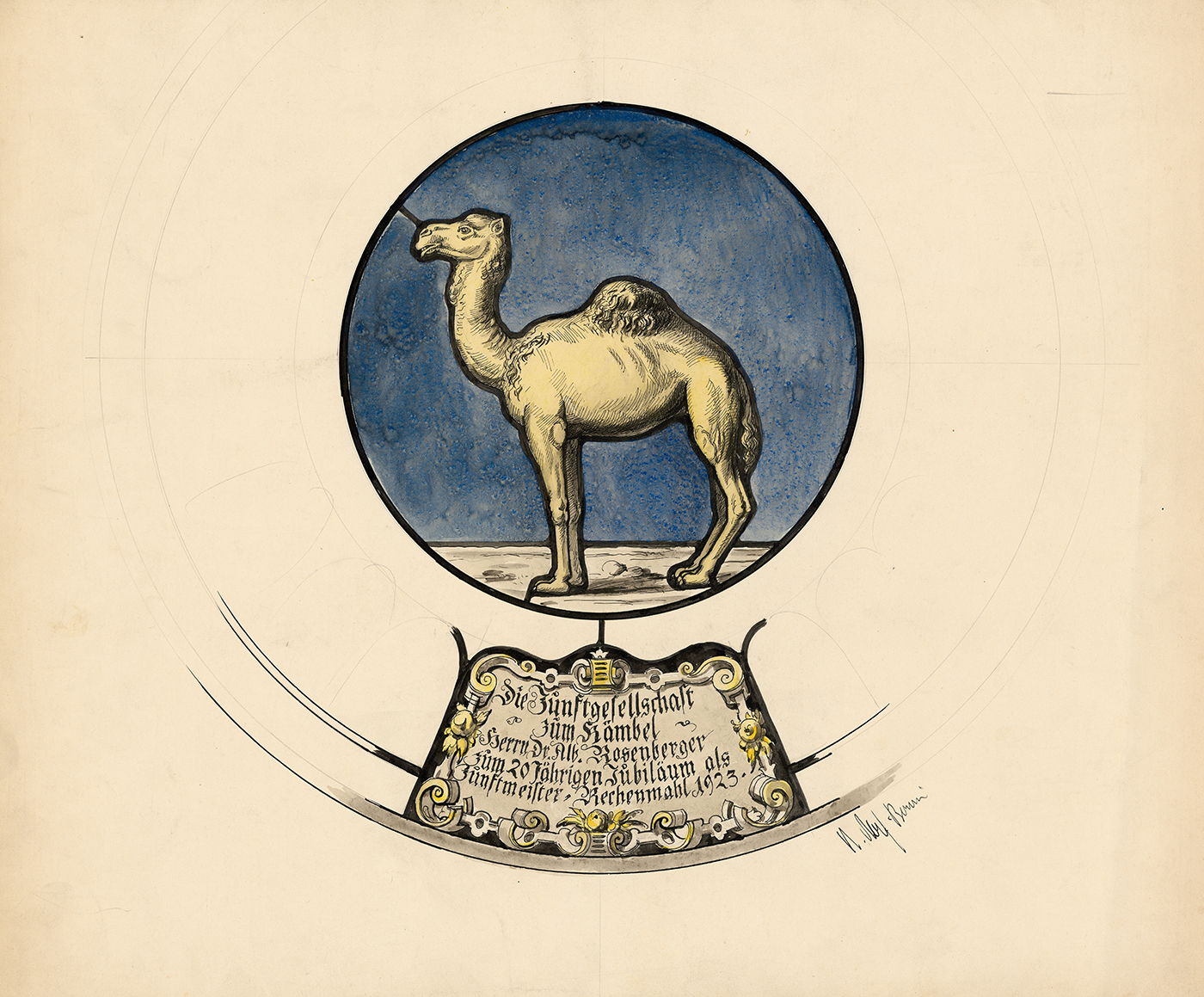

‘Kämbel’ Guild

Shopkeepers, vegetable and fruit sellers, oilers, salt-sellers, wine draymen, wine importers, butter merchants and oatmealers belonged to the ‘Kämbel’ (literally: ‘camel’) Guild. However, its members did not include officials dealing with the wine trade, who were affiliated with the ‘Meisen’ Guild.

According to Rudolf Hans Fürrer, the camel in the guild’s name and in the coat of arms is due to the furriers. In 1487, the guild took over the furriers’ ‘Haus zum Kämeltier’ (meaning: Angora goat). In day-to-day speech, this was shortened to ‘Kämbel’ (camel).

While the tailors opted for the Biedermeier style in the 19th century, the ‘Kämbel’ members stood out at the Sechseläuten: dressed as Bedouins and galloping apace around the Böögg snowman. To this day, they lay a wreath in front of the equestrian statue of their former guild master and mayor Hans Waldmann at the Fraumünster.

‘Waag’ Guild

The fact that Zurich’s textile industry was divided into three guilds in the First Sworn Charter is a reflection of its importance. The Tailors’ Guild is presented separately above. The wool weavers, wool-cleaners and hatters and the linen weavers and bleachers (of both sexes) united to form a guild in 1441, reducing the number of guilds to twelve.

Like the city of Zurich’s bakers, farriers, saddlers and dyers, the linen weavers included the Landmeisters, winners of national championships in their discipline, in their statutes so they could keep a closer eye on them. The journeymen also organised themselves. According to Otto Sigg, the wool-cleaner and weaver journeymen asked to be allowed to set up their own health insurance fund as early as 1336.

Obsolete professions still live on in surnames such as Wollschläger (‘wool-cleaner’) or Bleicher (‘bleacher’).

The ‘Constaffel’

It is also worth considering the ‘counterpart’ to the guilds, which emerged in 1336 from the old ruling class of nobles, pensioners and merchants. The ‘Constaffel’ was also a political, economic, military and social organisation, with its members sitting on Zurich’s council.

Constitutional revisions soon diminished the power of the mayor and the Constaffel alike. From 1490, the ‘Constaffel’ also included lower-class men and women who were not tied to any guild. Executioners, socially stigmatised figures, were part of this group, too. Families from independent trades increased their electoral chances by spreading themselves across the Constaffel and the guilds.

Today, the ‘Gesellschaft zur Constaffel’ is an association and still has its base in the ‘Rüden’. In the 21st century, it showed a strikingly open-minded approach by backing the only women’s guild, founded in 1989: the ‘Gesellschaft zu Fraumünster’ (‘Fraumünster Society’). This was invited to the Sechseläuten parade for the first time in 2011 and was allowed to join the procession as a permanent guest of the Constaffel from 2014 onwards.

We recommend Martin Illi’s book Die Constaffel (The Constaffel).

Private associations and patriotism after 1800

‘Honouring one’s homeland, serving one’s neighbour, cultivating friendship and believing in the future.’

founding motto of the ‘Schwamendingen’ Guild

The era of Zurich’s guilds came to an end with the collapse of the old Confederation in 1798: advances in transport and production, the expansion of trade and changes in employment conditions called for a freer economy.

But that wasn’t the end of the guilds, which re-formed as private citizens’ associations during the Helvetic Republic. Competition and disputes between guilds were replaced by friendly interaction shaped by feasts, poetry-readings and lectures. The cup of honour made its way around the guild rooms and songs were sung about friendship, holy harmony, courage, loyalty and trust in God.

Listen to guild poems from the 19th century:

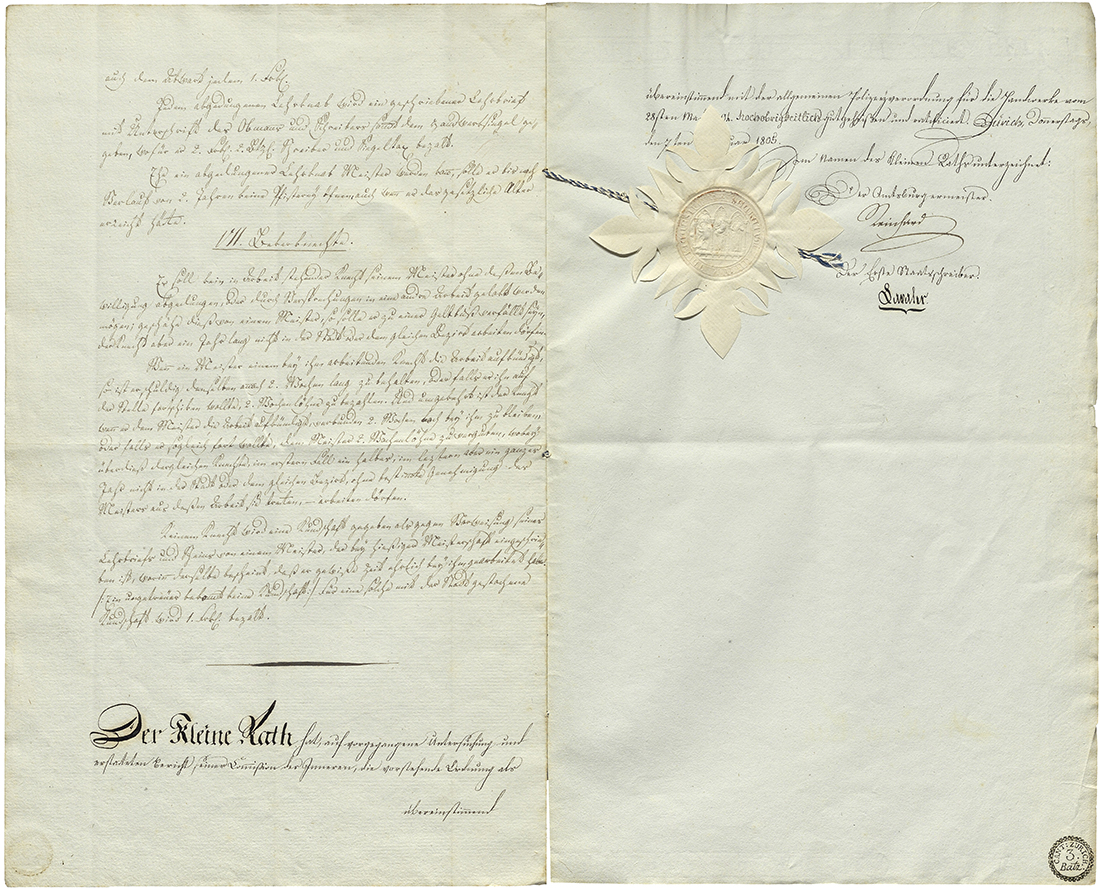

The Act of Mediation gave the guilds back the right to establish trade regulations and integrated them into the electoral system for the Grand Council – now together with master craftsmen from the countryside. From 1838 to 1866, they were merely constituencies for the city’s Grand Council.

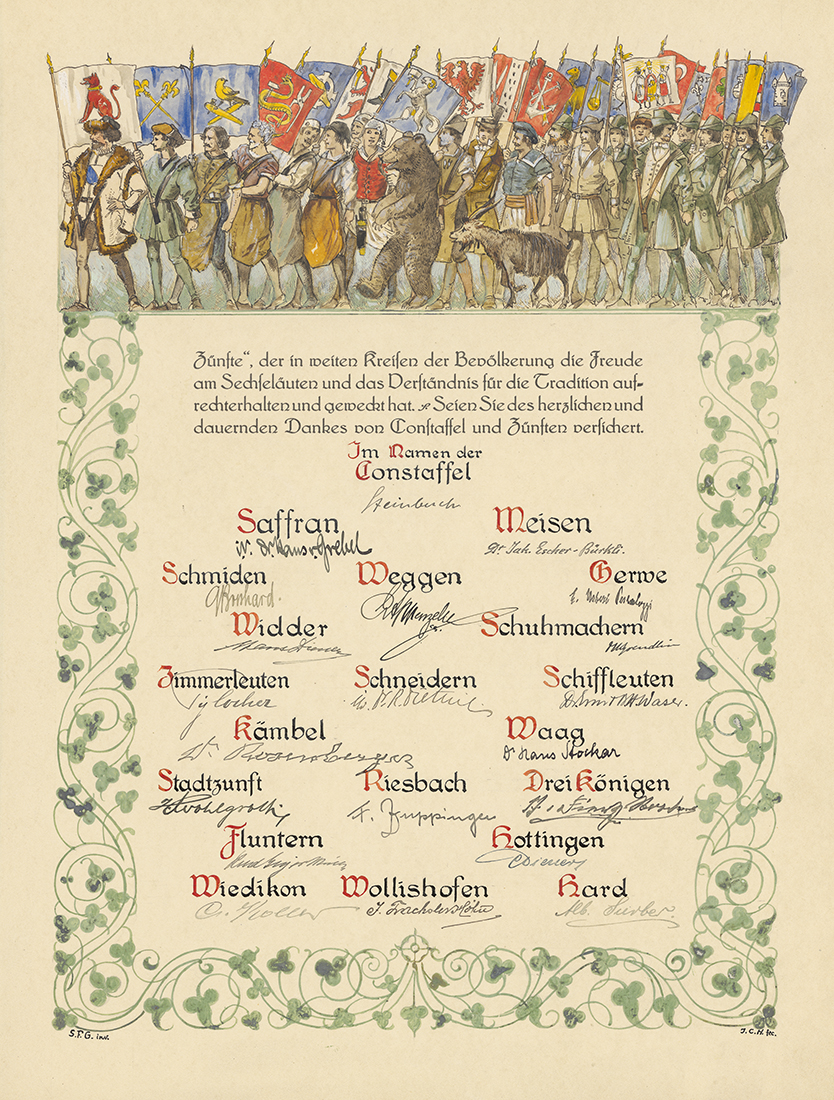

Today, the old craft guilds and the Constaffel are joined by the new guilds from the suburbs added in 1893/94.

Other guild customs throughout the year

Zurich’s guilds not only regulated and ritualised the world of work: they also shaped daily life, Sundays and public holidays via their recurring sequence of festivals and gatherings. The most famous guild event by far is the Sechseläuten spring festival. Here are certain other customs, some of which have survived to this day.

St. Berchtold’s Day

Traditionally, children brought the so-called ‘Stubenhitz’ maintenance contribution (wood, brushwood or money) to the guild house on 2 January and received food and drink in exchange. The same thing happened at other associations. In some places, this evolved into the custom of the New Year’s gazette as a gift to children in the 17th century.

The adult members of the guild celebrated the beginning of the year in their taverns with food, music and dancing. A list from 1792 reveals what was served: soup, green vegetables, chamois, boiled meat, fish, snails, wild duck, wild boar, brains, sausages, salad, wine and bread. For dessert, there was cream, compote, coffee and tea.

Today, St. Berchtold’s Day is a cantonal holiday, where people continue to celebrate alongside the guilds. Some associations even issue New Year’s gazettes – for adults.

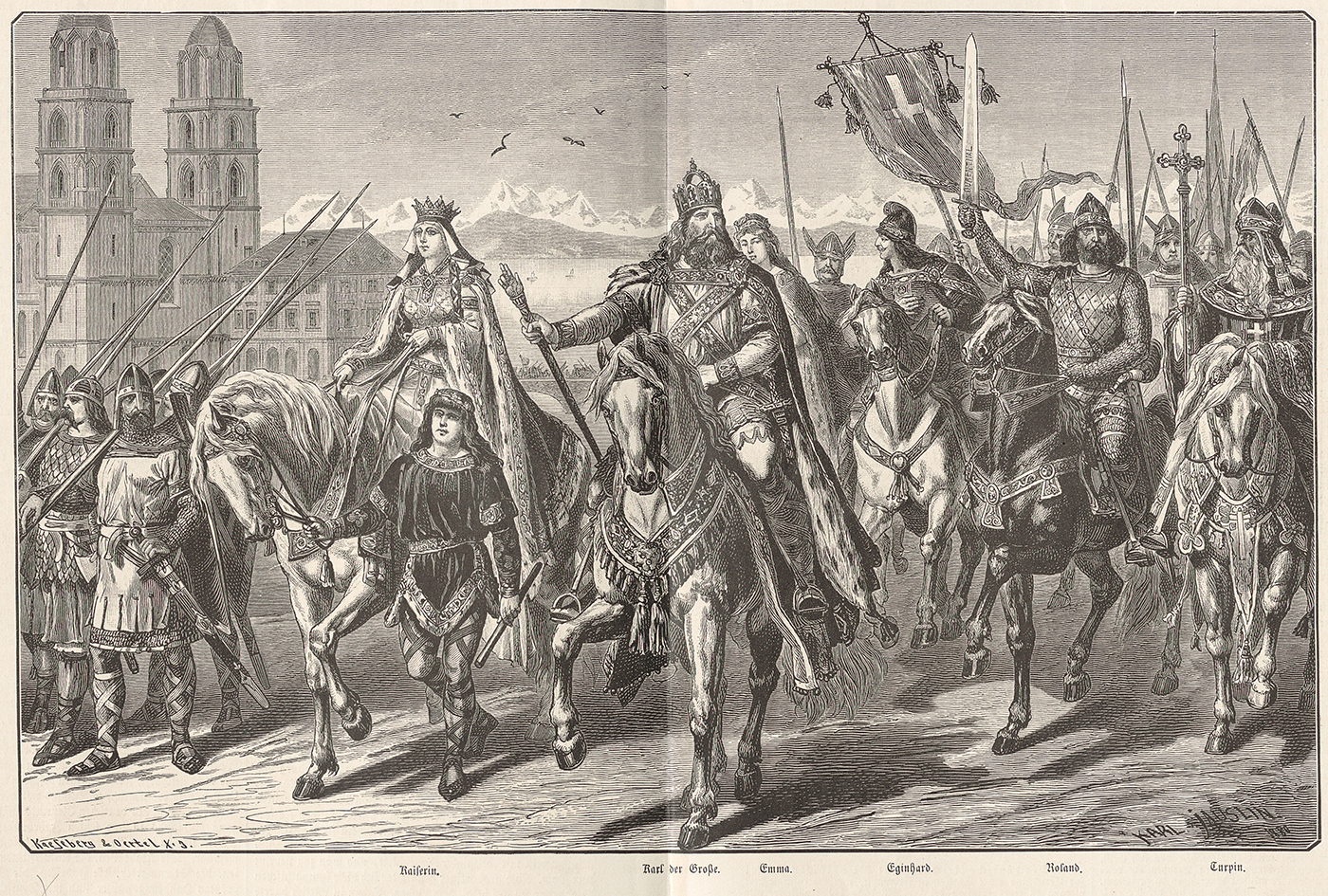

Karlstag (Charlemagne’s Day)

This celebration in honour of Charlemagne on 28 January was one of Zurich’s most important holidays until 1832. For four days, the aroma of fresh yeast rolls from the Höfli bakery wafted across the city. According to Markus Brühlmeier, these were distributed to the clergy and councillors and apparently eaten in abundance in the guild rooms. The guilds celebrated the emperor’s legendary visit to Zurich with banquets.

‘Of course, the tables were well equipped with silver and gold-plated drinking vessels, which almost served as a substitute for reliquaries in Zurich,’ reads the bulletin of the Antiquarian Society in Zurich.

Two tailors were part of Charlemagne’s retinue – and so the Tailors’ Guild chose him as its patron saint.

Ash Wednesday parade

Until 1728, the butchers of the ‘Widder’ Guild marched to the Lindenhof in a martial procession on Ash Wednesday, displaying a lion’s head. This frightening beast symbolised their lion-like courage on the night of murders in Zurich in 1350. As a further decoration of their military honour, ‘in line with the tastes of those times,’ as the New Year’s Gazette from 1785 puts it, their procession included a person hidden in a bear skin and tied in chains. It appears that the event was popular with children.

Later, it became customary for the guild to display the lion’s head next to a bear skin in the window of their guild house and give out cakes to any gawking children.

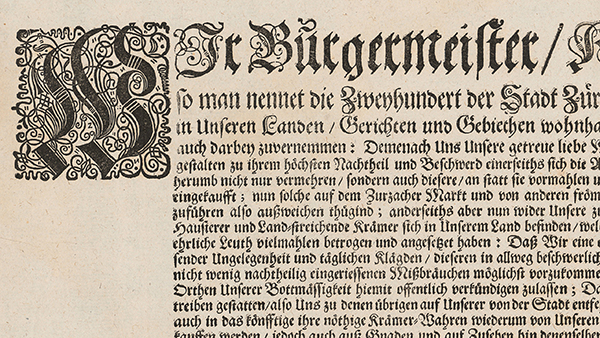

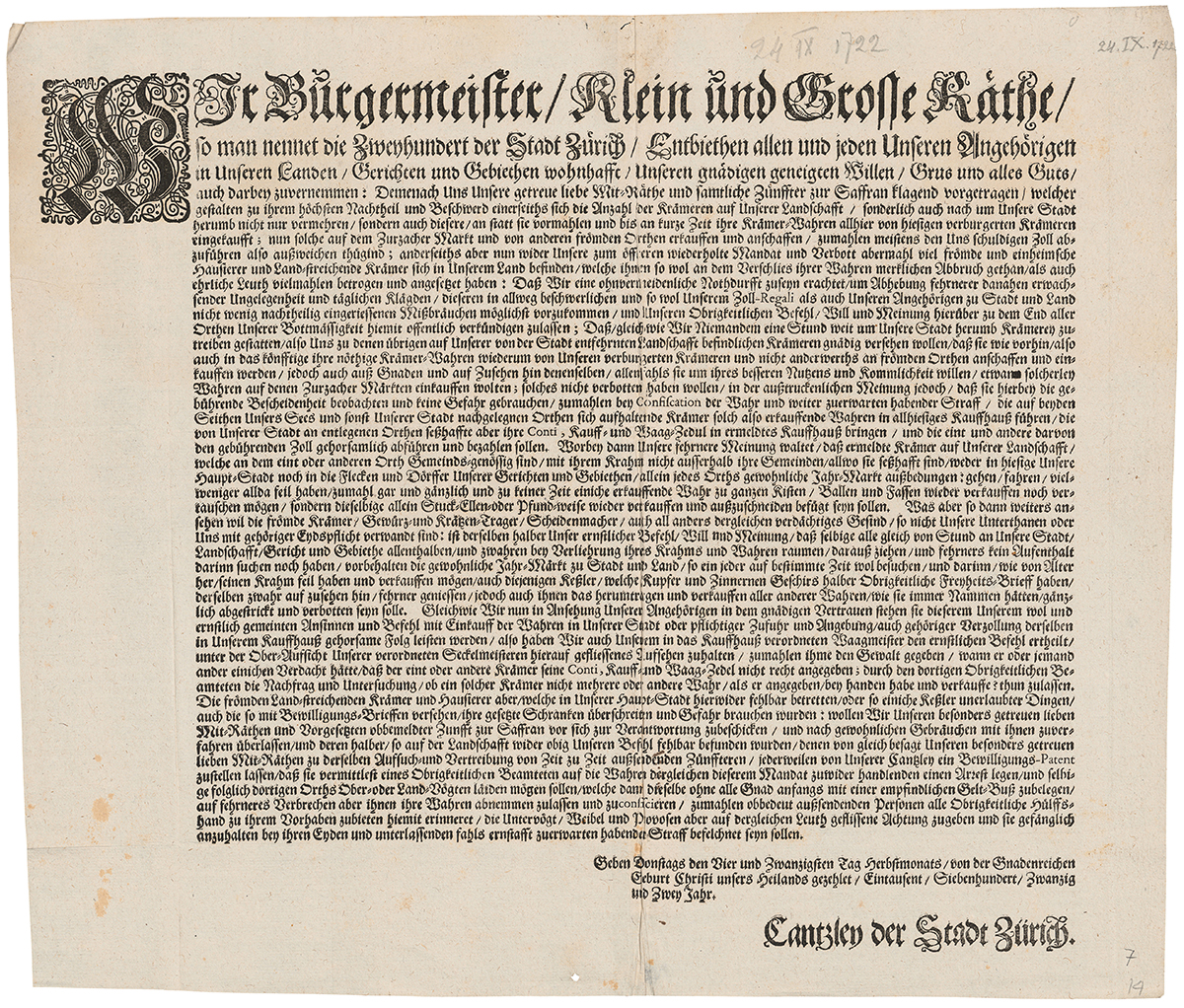

Mandatsonntag (Mandate Sunday)

Mandates from the authorities were distributed in print and read from the pulpit several times a year from the 16th century onwards: even the guilds also had to be told how to keep their Sunday rest, what meals to eat, how to set their prices or how to dress.

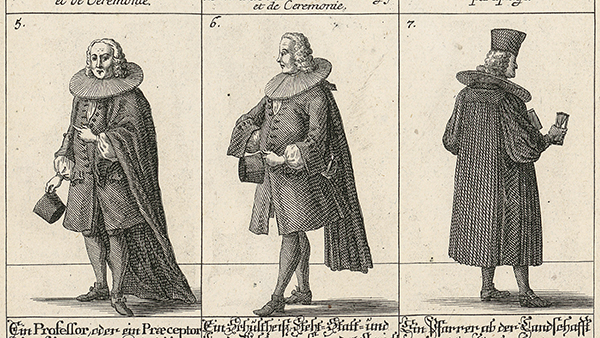

According to Markus Brühlmeier, the social status of a citizen of Zurich was visible externally. This could take the form of the small stand-up collar of the craftsmen and ‘ordinary citizens’ versus the large ruff worn by the councillors and guild directors, for instance.

The Synod of the Church and Zurich’s Council revised the regulations for the ‘promotion of a Christian and honourable change’ to suit the spirit of the times. In 1771, for example, they issued a clothing mandate forbidding the wearing of hoop skirts ‘as a fashion which nowadays gives rise to great and considerable expenditure’.

Meistertag (Masters’ Day)

Master craftsmen meetings, known as Meisterbotte, have been held twice a year since the Reformation. At these gatherings in May/June and December, internal posts were filled, new master craftsmen were accepted and the ‘most useful and best’ was appointed guild master for the coming semester. Being elected as guild master was a political promotion.

‘My decisions for the future are good, honest, patriotic, they benefit people. Whether and how I will be able to carry it out depends on a higher power that guides and directs everything,’ said guild master Johannes Bürkli to the ‘Widder’ Guild in 1783.

Secret elections became compulsory in 1713: guild members threw a penny into their chosen candidate’s ballot box.

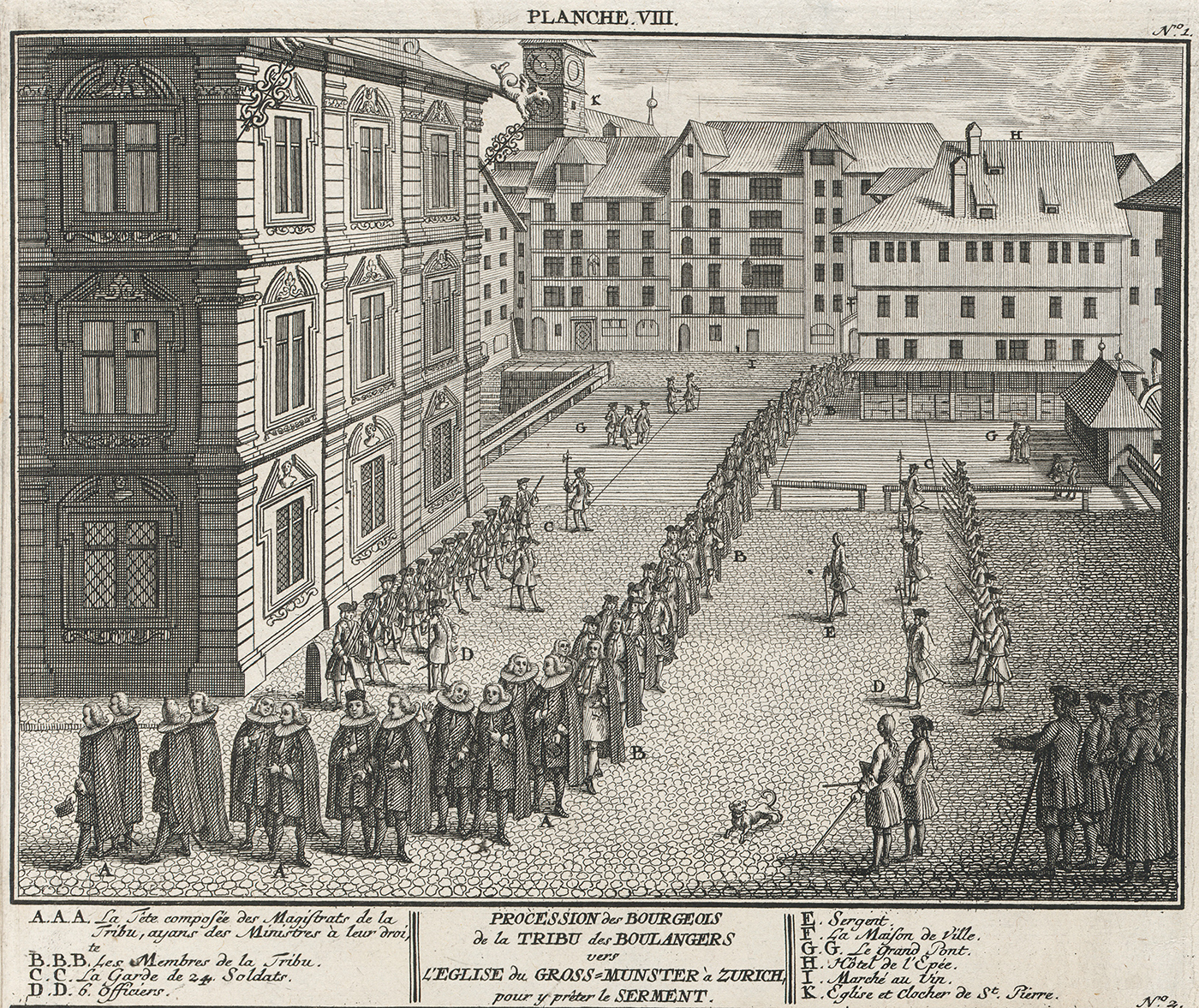

Schwörsonntag (Allegiance Sunday)

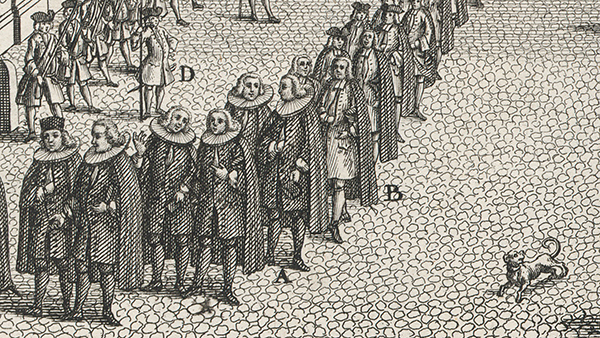

Half of Zurich was out and about on Schwörsunday: eight days after the biannual Masters’ Days, all male citizens over the age of 16 had to swear obedience to the mayor, the councillors and the guild masters in the Grossmünster. The renewed government, for its part, took an oath on the constitution and committed itself to city and country, church and guilds.

According to Markus Brühlmeier, Allegiance Sunday did not take place in the manner desired by the authorities – as the illustration by David Herrliberger from 1751 suggests. Guilds skipped the ritual or slipped away prematurely.

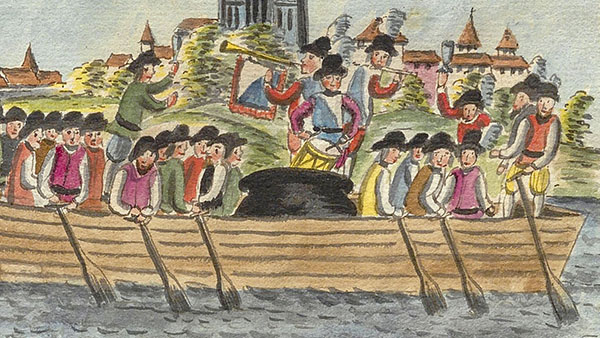

Schifferstechen (ship-jousting)

Even today, the Shipmen’s Guild (together with the Limmat Club Zurich) still holds its popular ‘Schifferstechen’ jousting event every three years in summer. Fortunately no one has been injured since the pointed lance was replaced by a blunt one and the heavy kit (comprising a helmet, armour and shield) by a lighter outfit.

What happens at the event? In the middle of the Limmat, two guilds each stand on a shaky boat facing each other. Holding lances, they try to push each other off the edge of the boat and into the water. The sporting competition, which is not only to be found in Zurich, is based on knight’s tournaments from medieval times, in which the opponent had to be thrown off their horse with the lance.

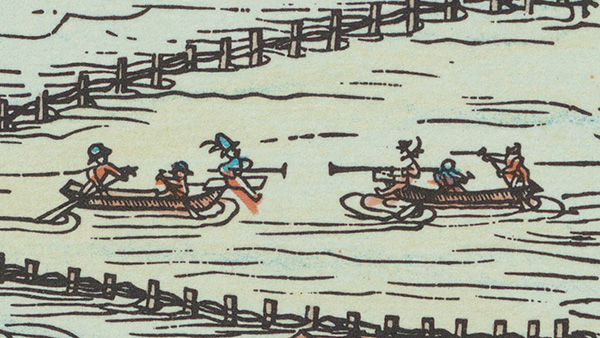

Hirsebreifahrt (literally: millet porridge ride) competition

It all started with a sporting bet. In 1456, Strasbourg invited competitors to take part in a free-shooting contest. A few members of Zurich’s Shipmen’s Guild and shooters signed up and managed to reach the Limmat in just 22 hours. As proof, they presented a pot of hot millet porridge.

In 1576, a group of guilds repeated the record trip in one day and again brought the residents of Strasbourg a pot of hot porridge as a sign of Zurich’s reliability, proximity and willingness to help. The ‘lucky’ journey has been described and illustrated many times.

Since the Second World War, the Hirsebreifahrt trip to the twinned city of Strasbourg has been repeated every 10 years – on traditional wooden long ships and, of course, with millet porridge. Weirs, dam walls and locks mean that the journey now takes 2.5 days.

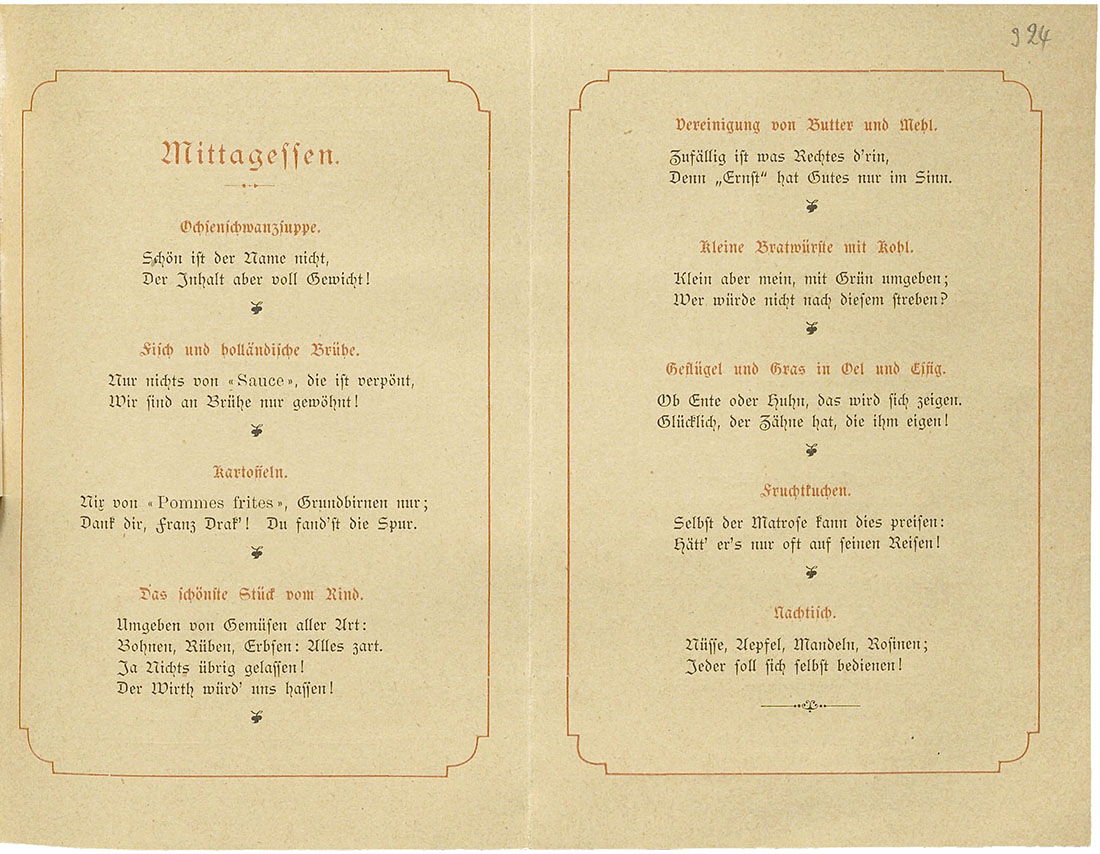

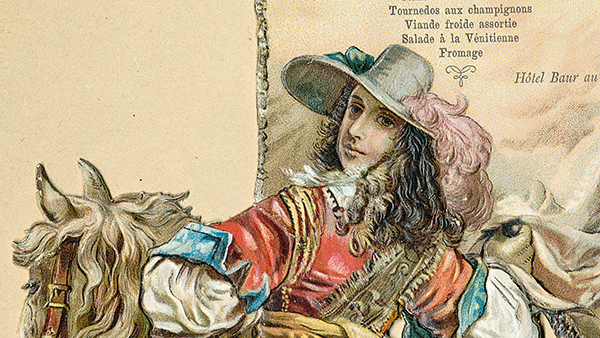

Guild meals

Meals were held in the taverns several times a year in addition to – or after – the political and commercial gatherings: meals after official meetings, banquets on St. Berchtold’s Day, Karlstag, Sechseläuten or St. Martin’s Day, as well as drinks to mark baptisms and weddings, and cup consecrations. The cost of these was covered either by the guild treasury or by the participants themselves.

The keeper of the guild’s tavern, together with his assistants or wife (the only administrative office that a woman was allowed to hold within the guilds) fulfilled the roles of innkeeper, organiser, secretary and caretaker.

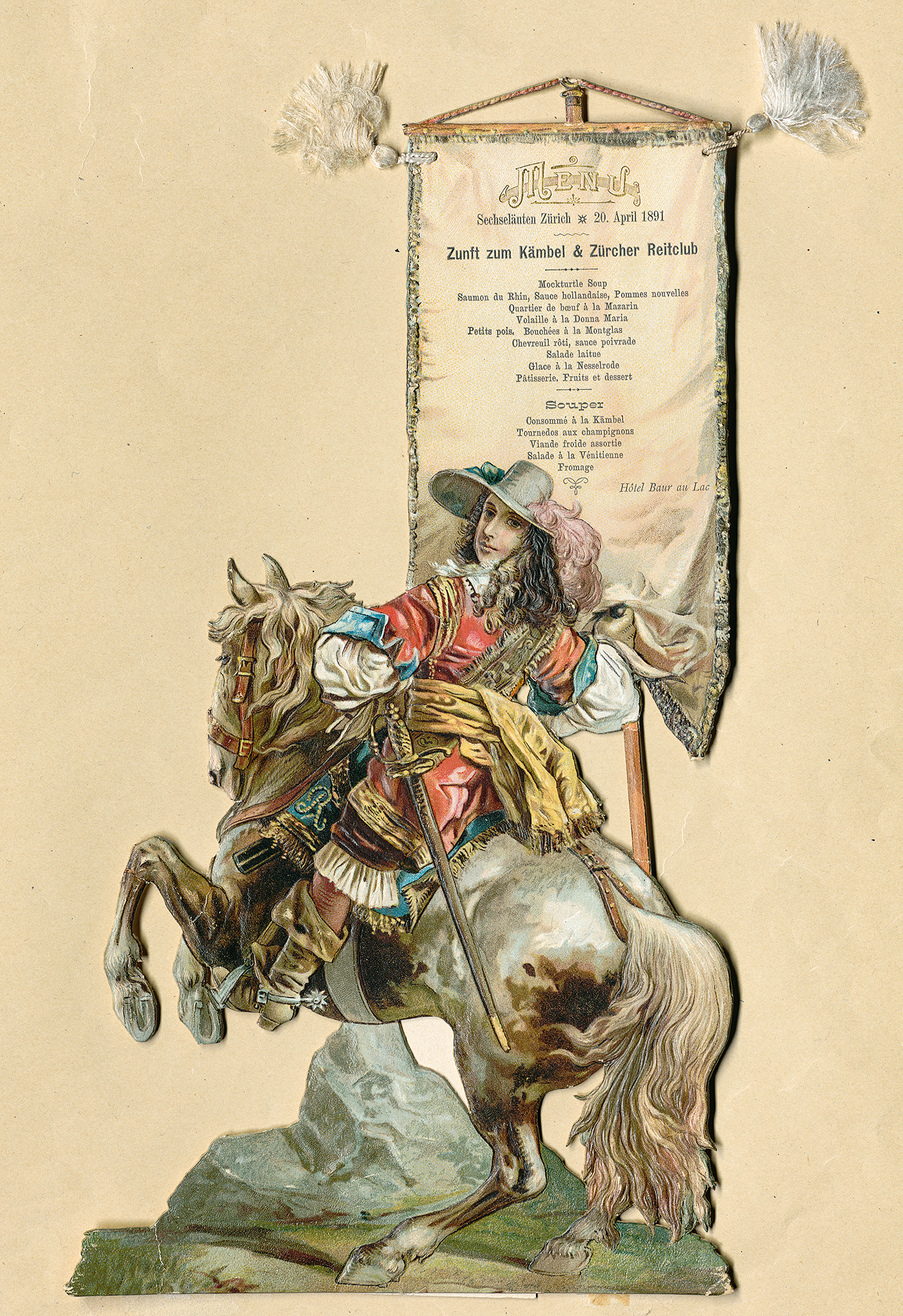

Invitations, programmes and menus from social gatherings in the 19th century have been preserved in the guild archives. They include this beautiful example from the ‘Kämbel’ Guild dating to 1891.

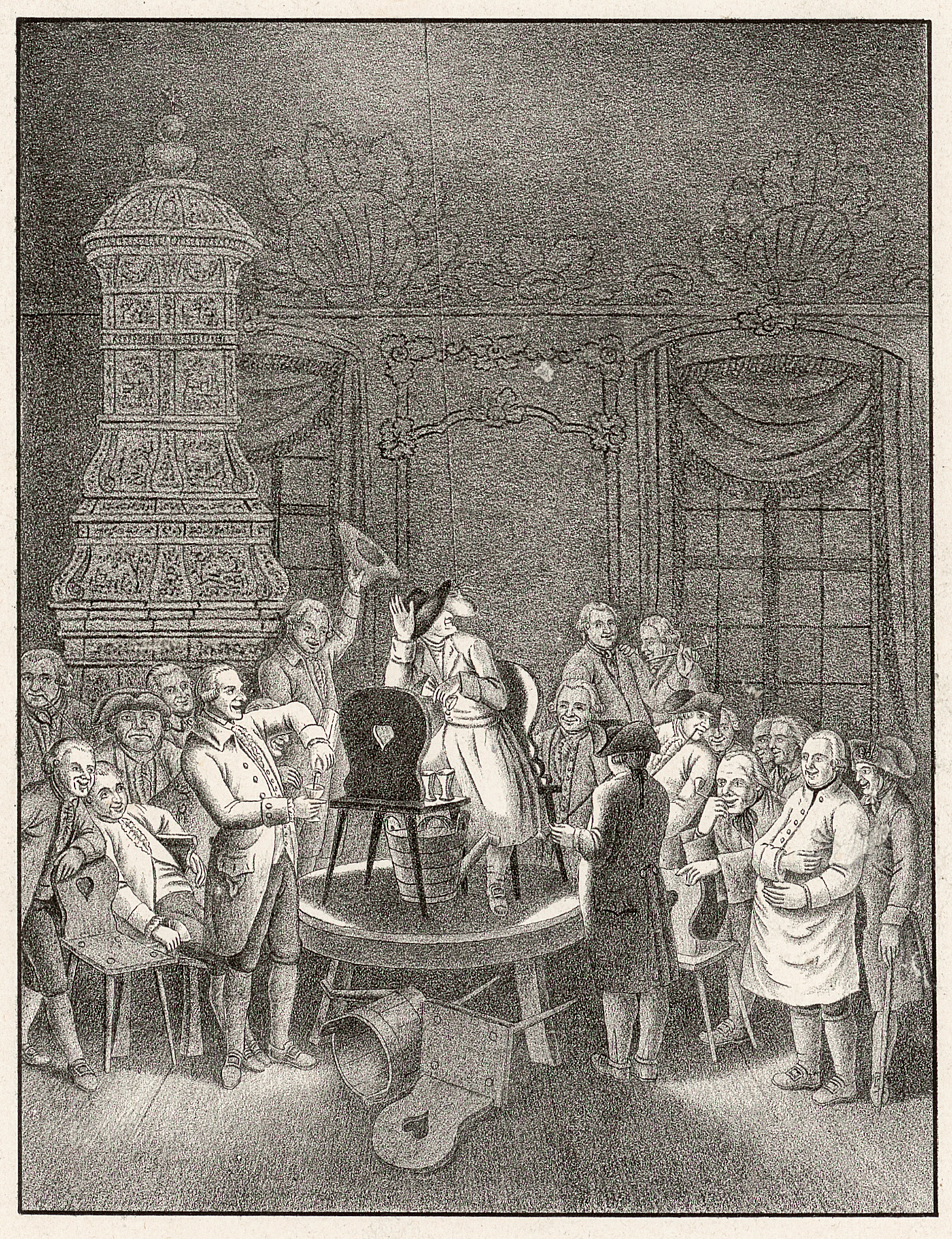

Drinking games

Die nach einer Zeichnung von Heinrich Freudweiler gedruckte Szene zeigt ein beliebtes Trinkspiel der Meisen-Zunft. Ein Mann mit breitkrempigem Hut sitzt auf einem Stuhl auf einem Tisch und versucht aus drei Weingläsern zu trinken, die vor ihm aufgestellt sind. Vor seinen Augen baumelt eine weisse Rübe. Er muss sie in Bewegung setzen und so geschickt um seinen Kopf kreisen lassen, dass er austrinken kann, ohne dass die Rübe seinen Hut berührt. Sonst wird nachgeschenkt.

Die Zunft zur Meisen pflegte auch das spätabendliche «Sidelerite» (Sesselreiten). Dabei «ritten» die Anwesenden auf ihren Stühlen munter die Treppe hinunter auf die Strasse hinaus und über die Brücke zum Helmhaus, wo die berittenen Stühle einen besonders schönen Lärm erzeugten, und wieder zurück.

Monica Seidler-Hux, research assistant in the Manuscript Department

April 2024

Header: excerpt from the Certificate of Congratulation to the President of the Central Committee of the Guilds, 1923.

(ZB Zürich, ZA Schn n. p.).